Gregorio Marañón facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

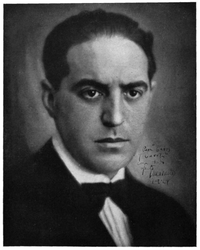

Gregorio Marañón

OWL

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 19 May 1887 Madrid, Spain.

|

| Died | 27 March 1960 (aged 72) Madrid, Spain.

|

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Citizenship | Spanish |

| Spouse(s) | Dolores Moya |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Endocrinology Psychology Historical essay |

Gregorio Marañón y Posadillo (born May 19, 1887, in Madrid – died March 27, 1960, in Madrid) was a very important Spanish doctor, scientist, historian, writer, and thinker. He was known for his wide range of knowledge. In 1911, he married Dolores Moya, and they had four children together: Carmen, Belén, María Isabel, and Gregorio.

Contents

A Life of Learning and Action

Gregorio Marañón was a serious and kind person who believed strongly in freedom and human rights. Many people consider him one of the smartest Spanish thinkers of the 20th century. He was not only very knowledgeable but also wrote in a beautiful and clear way.

Like many smart people of his time, he cared deeply about society and politics. He supported a republican government, which means a government where citizens elect their leaders. He spoke out against the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera, a time when one person had all the power. For this, he was even sent to jail for a month.

He also disagreed with communism in Spain. At first, he supported the Second Spanish Republic, a new government that replaced the monarchy. However, he later felt it was not bringing the Spanish people together.

Speaking Out for Freedom

During a difficult time in Spain, around 1937, Marañón left Madrid. When asked about the situation, he spoke to a group of French thinkers. He explained that many teachers in major Spanish cities had to leave the country. They were afraid of being harmed, even if they had left-wing ideas. This showed how much he valued freedom and safety for everyone.

From late 1936 to 1942, Marañón lived outside Spain. When he returned, the new government in Spain used his fame to look better to other countries. However, the government generally respected him. A historian named Miguel Artola said in 1987 that Marañón's biggest contribution was standing up for freedom. He did this when very few others dared to, seeing freedom as being against any single political idea that took away people's rights.

Marañón understood the Spanish government very well because of his experiences. After student protests in 1956, he joined other important figures like Menéndez Pidal. They spoke out against the harsh political situation and asked for people who had left Spain to be allowed to return.

Contributions to Medicine

Marañón's early work in medicine focused on a field called endocrinology. This is the study of hormones and the glands that make them. He was one of the first important doctors in this area.

In his first year of graduate school in 1909, he published several medical papers. One of them was about a condition related to hormones. In 1910, he published more papers, including some about Addison's disease, which affects the adrenal glands. His interest in endocrinology grew over the years.

In 1930, he published a major book called Endocrinology. He also wrote many articles for scientific journals on this topic. It's amazing that he did so much medical research while also being involved in the political changes of his time.

He also helped write the first textbook on internal medicine in Spain. His book, Manual of Etiologic Diagnostic (1946), became one of the most popular medical books worldwide. It was special because it offered a new way to study diseases and included many new findings from his own medical practice.

Beyond Medicine: A Man of Many Talents

Even though he was a dedicated doctor, Gregorio Marañón wrote about many other things. These included history, art, travel, cooking, clothing, and even hairstyles and shoes!

He created a special type of writing he called "biological essays." In these essays, he explored big human emotions and ideas by looking at famous historical figures. He studied their minds and bodies to understand things like:

- Shyness, through the writer Amiel.

- Resentment, through the Roman emperor Tiberius.

- Power, through the Spanish Count-Duke of Olivares.

- Intrigue and betrayal in politics, through Antonio Pérez.

- The idea of "donjuanism" (a charming but unfaithful character), through Don Juan.

He was also a member of five of the eight important Spanish Royal Academies, which are groups of experts in different fields.

Ramón Menéndez Pidal, another famous thinker, said that Marañón's influence was "indelible," meaning it could never be erased. This was true in science and in the relationships he built with others. Pedro Laín Entralgo, another doctor, saw five different sides to Marañón: the doctor, the writer, the historian, the moralist (someone who thinks about right and wrong), and the Spanish patriot. What made his work truly special was his "human" way of looking at everything. He connected science, ethics, morals, religion, culture, and history.

Gregorio Marañón was a doctor for the Royal Family and many famous people in Spain. But most importantly, he was a "beneficence doctor." This meant he treated the poorest people at the Hospital Provincial de Madrid. This hospital is now called Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. In 1911, he chose to work in the infectious diseases unit there. Today, his name is honored not only by this large hospital but also by many streets and schools across Spain.

The Marañón Foundation

The Gregorio Marañón Foundation was started on November 11, 1988. Its main goals are to keep Marañón's ideas and work alive. It also aims to spread the high standards of medicine he practiced and to support research in medicine and bioethics (the study of ethical issues in biology and medicine).

A big part of the Foundation's work is to find and collect all of Marañón's writings and life documents. This creates a special collection for anyone who wants to learn more about his ideas and work. Since 1990, a "Marañón Week" has been held every year to celebrate his legacy.

For example, in 1999, the Marañón Week focused on emotions. In 2001, it was about the figure of Don Juan. In 2009, it explored the idea of "liberal tradition," which means believing in individual rights and freedoms.

On July 9, 2010, the Gregorio Marañón Foundation joined with another important group, the José Ortega y Gasset Foundation. They formed a new organization called the José Ortega y Gasset-Gregorio Marañón Foundation.

Ateneo of Madrid

The Ateneo of Madrid, a famous cultural and scientific institution, celebrated the 50th anniversary of Marañón's death in 2010. Gregorio Marañón had a strong connection to the Ateneo. In 1924, its members wanted him to be their president. Even though a dictatorship prevented a proper election, he was seen as the true leader. He was officially appointed president of the Ateneo in March 1930.

Lasting Legacy

A medical sign called Marañón’s sign is named after him. This sign helps doctors suspect if a patient has a goiter (a swelling in the neck) that is hidden behind the breastbone.

Books

- Tiberius: A Study in Resentment (1956) – This book was translated from his Spanish work Tiberio: Historia de un resentimiento (1939).

See also

In Spanish: Gregorio Marañón para niños

In Spanish: Gregorio Marañón para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |