Grinton Smelt Mill facts for kids

Grinton Mill and new (2020) rock-amour watercourse

|

|

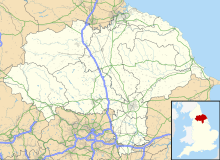

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Location | Grinton |

| County | North Yorkshire |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 54°21′48″N 1°55′35″W / 54.3633°N 1.9264°W |

| Production | |

| Products | Lead |

| Production | 100 tonnes (110 tons) |

| Financial year | 1739–1740 |

| History | |

| Opened | 1822 |

| Closed | 1886–1895 |

The Grinton Smelt Mill (also called How Mill) is a ruined site where lead was mined and processed. It is located on Cogden Moor, south of Grinton in Swaledale, North Yorkshire, England. The mill you see today was built around 1820. Its main job was to process lead that was found using special mining methods like hushing (using water to expose ore) and hydraulic mining (using water pressure).

The buildings and a long stone tunnel (called a flue) are now protected as important historical sites. They are known as grade II* listed structures and scheduled monuments. This means they are very important and kept safe. Many people believe it is the best-preserved lead mining site in the Yorkshire Dales. An earlier mill was here in the 1700s. The later mill added a 300-metre (980 ft) flue. This helped workers collect leftover lead from the smoke.

Contents

History of Lead Mining in Grinton

Lead mining has a long history in the Yorkshire Dales. People were mining lead here even before Roman times. The first written records about lead mining in the Grinton area are from 1219. The land was owned by different groups, but the Crown (the King or Queen) kept the rights to any minerals found.

Where the Lead Came From

The lead processed at Grinton Smelt Mill came from the Grinton How Vein. This vein was mined at places like Grinton How, Whiteside, and Fearnought Mines. Lead ore is very heavy. Because of this, smelt mills were built close to where the lead was found. This is why there were over 30 mills in Swaledale alone! Grinton Mill was also known as How Mill. This was because it processed lead from the How Vein. It was also called Low Mill. This name came from another mill, Grovebeck Mill, which was about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) west and 100 metres (330 ft) higher.

Early Days and Disputes

Grinton Smelt Mill is about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) south of Grinton. It is also 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) north-west of Leyburn. The first mill on this site was built around 1727 by William Marriott. However, mining was happening in the area long before that.

In 1696, Reginald Marriott, a relative of William, got permission to mine the area. This led to a big argument with Lord Wharton. Lord Wharton was a local landowner. He claimed the land and started his own mines very close to Marriott's. This argument went to court in 1705. It involved over 317 witnesses and lasted three years! The court decided in favor of Marriott. Lord Wharton threatened more legal action, but the case never went back to court. It's thought that the price of lead dropped, so he lost interest. In 1720, Marriott extended his lease until 1727. He had to pay one-eighth of his earnings to the Crown. This shows that the business must have been very profitable for him.

The London Lead Company and Production

The London Lead Company (LLC) might have bought the site from Marriott in 1733. They may have also put in new furnaces. However, some modern research suggests that the LLC might not have operated in Swaledale at all. During the 1730s, Grinton Mill produced over 100 tonnes (98 long tons) of lead each year. This was the final product, not the amount of raw ore mined.

Building the Modern Mill

The mill buildings you see today were built between 1820 and 1822. Many historians think the whole site was rebuilt during this time. This is because there was a long gap between the old mill closing and the new one starting full production. Originally, there were three buildings. Only the main mill and the peat store are left. The third building, called the Smithy, was torn down in the 1960s.

The main mill building is 16 metres (53 ft) long and 11 metres (36 ft) wide. Lead smelting happened in this main room. Peat (a type of fuel) was stored next door. It was fed into the mill through chutes. The main room had three hearths (fireplaces) for roasting the lead ore. Behind this was the bellows room, which was 4.9 metres (16 ft) by 7.9 metres (26 ft).

Outside the bellows room was a large waterwheel. It was about 6.1 metres (20 ft) across and 500 millimetres (20 in) wide. This waterwheel powered the bellows, which pumped air into the furnaces. Peat was brought from the nearby moorland by horse and cart. The large open arches in the peat house helped dry the peat.

The Flue and Water System

A long flue (tunnel) stretched 300 metres (980 ft) eastwards up the hill. It ended at the top of Sharrow Hill, 370 metres (1,210 ft) above sea level. The chimney at the end was about 2.7 metres (9 ft) wide on each side. Inside, the flue was 1.8 metres (5 ft 11 in) high and 1.6 metres (5 ft 3 in) wide. A longer flue allowed more lead to be collected from the waste gases. Small boys were hired to scrape the toxic dust from the flue's walls. They used access holes on the south side of the flue.

Just west of the mill was a 12-metre (40 ft) long stone tunnel. This tunnel carried Cogden Beck water away from the mill. This water was overflow from a man-made reservoir. The reservoir was built on higher ground to the south of the mill. Water from the reservoir flowed into the mill through a "wobbly aqueduct" called a launder. This launder carried water at roof height, about 3.0 metres (10 ft) above the waterwheel's axle. This height helped power the large waterwheel. The waterwheel then activated the bellows, keeping the furnaces supplied with air for smelting the lead.

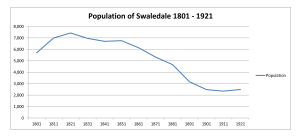

The lead mining industry greatly affected the population of Swaledale. The graph shows how the population changed over 120 years. Between 1829 and 1833, the lead industry faced problems, and the number of miners dropped. After that, the number of people living in the area continued to fall. This was partly because cheaper lead was being imported from other countries.

Closure and Later Use

Grinton Mill closed at different times according to various sources. Some say it closed in 1886. Others suggest a company called the Grinton Mining and Smelting Company refurbished the furnaces and kept them working until 1893. A newspaper report from 1887 said the mine closed in 1886. However, a new company had secured a 21-year lease to continue mining.

After the mill stopped smelting lead, it was used for other purposes. It became a sheep dip (where sheep are washed) and a shelter for cattle. A new roof was added in 1987 to help protect it. The site is a scheduled monument. The buildings, including the stone watercourse, are listed as grade II*. It is known as the best-preserved lead mining and smelting site in the Yorkshire Dales. In 1998, another £16,000 was spent on renovating the mill. This money came from the Yorkshire Dales National Park and an EU fund.

Recent Flooding and Repairs

In July 2019, heavy flash flooding hit Wensleydale and Swaledale. The powerful waters of Cogden Gill washed away the barrel-arched watercourse. This was the tunnel the water flowed through. The floods also destroyed a stone bridge on the road to Grinton. This bridge was the usual route for lead ore to leave the site. In early 2020, work was done to protect the main mill building. This work helped prevent future water damage and sinking of the ground.

Gallery

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |