H. L. Hunley (submarine) facts for kids

class="infobox " style="float: right; clear: right; width: 315px; border-spacing: 2px; text-align: left; font-size: 90%;"

| colspan="2" style="text-align: center; font-size: 90%; line-height: 1.5em;" |

|} The H. L. Hunley was a special kind of submarine used by the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. It showed both the amazing possibilities and the dangers of fighting underwater.

The Hunley was the first combat submarine to sink an enemy warship. It attacked the USS Housatonic in 1864. However, after its successful attack, the Hunley and its crew were lost at sea.

During its short time in service, the Hunley sank three times. In total, 21 crew members lost their lives. The submarine was named after its inventor, Horace Lawson Hunley. It was taken over by the Confederate States Army in Charleston, South Carolina.

The Hunley was almost 40 ft (12 m) long. It was built in Mobile, Alabama, and launched in July 1863. It was then moved by train to Charleston in August 1863.

The submarine, sometimes called the "fish boat," sank twice during test runs. On August 29, 1863, five crew members died. Then, on October 15, 1863, all eight crew members, including Horace Lawson Hunley himself, were lost. Both times, the Hunley was brought back up and repaired.

On February 17, 1864, the Hunley attacked and sank the USS Housatonic. This was a large United States Navy ship that was blocking Charleston's harbor. The Hunley did not return from this mission. All eight of its crew members were lost.

The Hunley was finally found in 1995 and raised in 2000. Today, you can see it in North Charleston, South Carolina. Experts believe the Hunley was very close to the Housatonic when its torpedo exploded. This explosion likely caused the Hunley to sink as well.

Contents

- Early Submarines

- Building and Testing the Hunley

- Hunley Weapons

- Attack on the Housatonic

- Finding the Hunley Wreck

- The Crew

- Tours

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Submarines

Before the Hunley, Horace Lawson Hunley helped fund two other submarines. These were the Pioneer and the American Diver.

The Pioneer was tested in New Orleans in 1862. But when Union forces advanced, the builders had to sink the Pioneer to keep it from being captured.

Hunley and his team then moved to Mobile, Alabama. There, they built the American Diver. They tried different ways to power it, like electricity and steam. But they ended up using a simple hand-crank system.

The American Diver was ready by January 1863. However, it was too slow to be useful. They tried to tow it to attack Union ships, but it sank in bad weather. Luckily, the crew escaped.

Building and Testing the Hunley

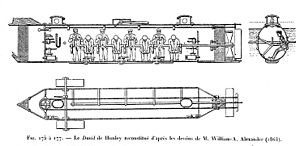

Inboard profile and plan drawings of the Hunley(1863)

Horace Lawson Hunley, the submarine's inventor

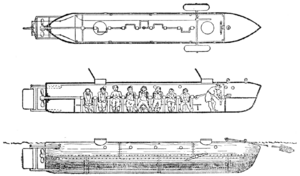

Drawings of H. L. Hunleyfrom 1900.

Building the Hunley started soon after the American Diver was lost. People sometimes called it the "fish boat" or "porpoise." Some thought it was made from an old boiler, but it was actually designed and built specifically as a submarine.

The Hunley was built for a crew of eight. Seven crew members would turn a hand-crank to power the propeller. One person would steer the submarine.

The submarine had tanks at each end that could be filled with water to make it dive. They could also be pumped dry to make it rise. Heavy iron weights were bolted to the bottom for extra balance. If there was an emergency, these weights could be released to help the submarine float up quickly.

The Hunley had two hatches, one at the front and one at the back. These were on top of small conning towers with tiny windows. The hatches were quite small, making it hard to get in and out.

By July 1863, the Hunley was ready for a demonstration. It successfully attacked a coal boat in Mobile Bay. After this, it was sent by train to Charleston, South Carolina.

When it arrived, the Confederate military took control of the submarine. It became a Confederate Army vessel. Even though it's sometimes called CSS Hunley, it was never officially part of the Navy.

Lieutenant John A. Payne volunteered to be the Hunley's captain. On August 29, 1863, during a test dive, Lieutenant Payne accidentally stepped on a lever. This caused the submarine to dive with a hatch open. Payne and two others escaped, but five crewmen drowned.

After this, General P. G. T. Beauregard put Lieutenant George E. Dixon in charge. On October 15, 1863, the Hunley failed to surface after a practice attack. All eight crewmen died, including Horace Hunley himself. He had joined the crew for the exercise. The submarine was raised again and put back into service.

Hunley Weapons

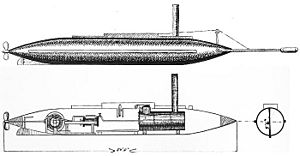

Plans of CSS David

The Hunley was first planned to use an explosive charge towed behind it. The idea was to dive under an enemy ship, then surface, letting the explosive hit the ship. But this was too risky because the rope could get tangled.

Instead, the Hunley used a spar torpedo. This was a copper cylinder with 135 pounds (61 kilograms) of black powder. It was attached to a 22-foot (6.7 m)-long wooden pole at the front of the submarine.

The Hunley would ram this spar into the side of an enemy ship. The torpedo was designed to explode on contact. Later, an iron pipe was added to the bow. This pipe angled downwards to deliver the explosive charge deeper underwater.

Attack on the Housatonic

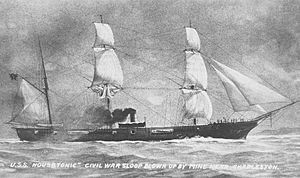

USS Housatonic

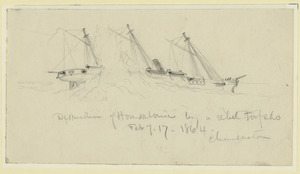

Destruction of the USS Housatonic; sketch by war artist William Waud.

The Hunley made its only real attack on February 17, 1864. Its target was the USS Housatonic. This was a large wooden steamship with 12 cannons. It was blocking the entrance to Charleston harbor.

Lieutenant George E. Dixon and his seven volunteer crew members successfully attacked the Housatonic. They rammed the spar torpedo into the enemy ship's side. The torpedo exploded, and the Housatonic sank in about five minutes. Five of its crew members died.

After the attack, the H.L. Hunley did not return to its base. For a long time, people wondered what happened. Some thought it might have been hit by another ship. But when the Hunley was found, there was no such damage.

Scientists now believe the Hunley's crew died instantly from the explosion of their own torpedo. The powerful blast likely sent shockwaves through the water and into the submarine. This could have caused serious injuries to the crew without damaging the submarine's hull.

Evidence shows the crew did not try to escape. Their skeletons were found at their stations. Also, the special weights that could be released for an emergency escape were still attached. This suggests they died very quickly.

Finding the Hunley Wreck

H. L. Hunley, suspended from a crane during its recovery, August 8, 2000

Removing the first section of the crew's bench at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, January 28, 2005

H. L. Hunleyin sodium hydroxide bath, July 2017

The discovery of the Hunley was a very important find. It was buried under several feet of mud and sand. This protected the submarine for over 100 years.

Diver Ralph Wilbanks found the wreck in April 1995. He was leading a team funded by novelist Clive Cussler. The submarine was found about 100 yd (91 m) away from the Housatonic, on the ocean side.

On August 8, 2000, the Hunley was carefully raised from the ocean floor. A large team of experts worked together. The submarine was lifted by a crane and placed on a barge.

At 8:37 AM, the Hunley broke the surface for the first time in over 136 years. Crowds cheered from the shore and nearby boats. The submarine was then taken to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in North Charleston. There, it was placed in a special tank of fresh water to keep it safe.

The Crew

H.L. Hunley Memorial Marker at Magnolia Cemetery

The final crew of the Hunley included Lieutenant George E. Dixon, Frank Collins, Joseph F. Ridgaway, James A. Wicks, Arnold Becker, Corporal Johan Frederik Carlsen, C. Lumpkin, and Augustus Miller.

For a long time, the identities of these volunteer crewmen were a mystery. Scientists examined their remains. They found that four of the men were American, and four were from Europe. This was figured out by looking at what they ate, which left clues in their teeth and bones.

Through research and DNA testing, experts identified Dixon and the three other Americans. Identifying the European crewmen was harder, but it seems they were identified in 2004.

On April 17, 2004, the remains of the crew were buried at Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston.

A surprising discovery was made in 2002. Researchers found a bent $20 gold coin near Lieutenant Dixon. It had an inscription: "Shiloh April 6, 1862 My life Preserver G. E. D."

This coin matched a family story. Dixon's sweetheart had supposedly given him the coin for protection. At the Battle of Shiloh, a bullet hit the coin in his pocket. This saved his leg and possibly his life. He had the coin engraved and carried it as a lucky charm.

Tours

You can visit the Hunley at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in Charleston on weekends. The actual Hunley is kept in a tank of water. There is also a replica that visitors can go inside. The center has artifacts found inside the submarine and videos about its history.

Images for kids

CSS Chicora and CSS Palmetto State

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | H. L. Hunley |

| Namesake | Horace Lawson Hunley |

| Builder | James McClintock |

| Laid down | Early 1863 |

| Launched | July 1863 |

| Acquired | August 1863 |

| In service | 17 February 1864 |

| Out of service | 17 February 1864 |

| Status | Awaiting conservation |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement | 7.5 short tons (6.8 t) |

| Length | 39.5 ft (12.0 m) (unconfirmed) |

| Beam | 3.83 ft (1.17 m) |

| Propulsion | Hand-cranked ducted propeller |

| Speed | 4 kn (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph) (surface) |

| Complement | 2 officer, 6 enlisted |

| Armament | 1 spar torpedo |

|

H. L. HUNLEY (submarine)

|

|

| Nearest city | North Charleston, South Carolina |

| Built | 1864 |

| Architect | Park & Lyons; Hunley, McClintock & Watson |

| NRHP reference No. | 78003412 |

| Added to NRHP | December 29, 1978 |

See also

In Spanish: H. L. Hunley (submarino) para niños

In Spanish: H. L. Hunley (submarino) para niños