Halton Arp facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Halton Arp

|

|

|---|---|

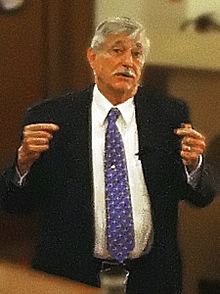

Halton Arp in London, October 2000

|

|

| Born | March 21, 1927 New York City, United States

|

| Died | December 28, 2013 (aged 86) Munich, Germany

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | California Institute of Technology |

| Known for | Intrinsic redshift Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies |

| Awards | Newcomb Cleveland Prize (1960) Helen B. Warner Prize for Astronomy (1960) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Institutions | Palomar Observatory Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics |

| Doctoral advisor | Walter Baade |

| Doctoral students | Susan Kayser |

Halton Christian "Chip" Arp (March 21, 1927 – December 28, 2013) was an American astronomer. He was famous for his 1966 book, Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies. This book showed many examples of galaxies that were crashing into each other or merging. However, Arp thought these galaxies were actually shooting out material.

Arp was also known for disagreeing with the Big Bang theory, which explains how the universe began. He believed in a different idea called non-standard cosmology, which included something called intrinsic redshift.

Contents

About Halton Arp

Halton Arp was born in New York City on March 21, 1927. He went to Harvard University and earned his first degree in 1949. Later, he got his PhD from Caltech in 1953.

After finishing school, Arp worked at important places like the Mount Wilson Observatory and Palomar Observatory. In 1957, he became a staff member at Palomar Observatory, where he worked for 29 years. In 1983, he moved to Germany to join the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics. He passed away in Munich, Germany, on December 28, 2013.

His Book: Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies

In 1966, Arp put together a special collection of unusual galaxies called the Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies. He realized that scientists didn't know much about how galaxies change over time. So, he created this atlas to give astronomers pictures and information to study how galaxies grow and evolve.

Today, other astronomers see Arp's atlas as a great collection of galaxies that are bumping into each other and merging. Many of these galaxies are still called by their "Arp number." For example, Arp 220 is a very famous one.

However, Arp himself didn't believe these galaxies were merging. He thought they were actually shooting out material from a main galaxy.

Quasars and Redshift Ideas

In the 1950s, scientists found very bright objects in space that sent out strong radio signals. These objects are now called quasars. In 1963, astronomer Maarten Schmidt studied one of these quasars, 3C 273. He found that its light was very "redshifted."

Imagine a siren on an ambulance: the sound changes pitch as it moves away. Light does something similar. When objects in space move away from us, their light gets stretched, making it appear redder. This is called "redshift." The more redshifted an object's light is, the faster it's moving away and the farther away it is.

Schmidt suggested that quasars were extremely far away and incredibly bright. This idea fit with the universe expanding, as described by Hubble's law.

However, Halton Arp had a different idea. In 1967, he noticed that some quasars seemed to be very close to certain galaxies in his Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies. In some pictures, it even looked like there was a bridge of matter connecting them. If they were truly close, they should have similar redshifts. But the galaxies had much smaller redshifts than the quasars.

Arp argued that the redshift of quasars wasn't always because they were far away and moving with the expanding universe. He thought some quasars had an "intrinsic redshift"—a redshift that came from something inside them, not from their distance. He believed these quasars were actually closer to us and had been shot out from the centers of active galaxies.

Since the 1960s, telescopes and space tools have gotten much better. The Hubble Space Telescope was launched, and we've learned a lot more about the universe. Scientists have found black holes and studied very distant objects. Most astronomers now agree that quasars are very distant, active galaxies with high redshifts, meaning they are very far away.

Even with these new discoveries, Arp never changed his mind about the Big Bang theory. He continued to publish articles explaining his different views until he passed away in 2013. He believed his research on quasars showed that the Big Bang theory was wrong. Instead, he supported the idea of redshift quantization, which suggests redshifts come in specific steps.

Awards and Recognition

Halton Arp received several important awards for his work:

- In 1960, he won the Helen B. Warner Prize for Astronomy from the American Astronomical Society. This award is given for important contributions to astronomy.

- In the same year, he also received the Newcomb Cleveland Prize for his talk called "The Stellar Content of Galaxies."

- In 1984, he was given the Alexander von Humboldt Senior Scientist Award.

Books by Halton Arp

- Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies (1966)

- The Redshift Controversy (1973, with George B. Field and John N. Bahcall)

- Quasars, Redshifts and Controversies (1987)

- Seeing Red: Redshifts, Cosmology and Academic Science (1998)

- Catalogue of Discordant Redshift Associations (2003)

See also

In Spanish: Halton Arp para niños

In Spanish: Halton Arp para niños

- Cosmology

- Non-standard cosmology

- Intrinsic redshifts

- Redshift quantization

- Le Sage's theory of gravitation

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |