Hannah Snell facts for kids

Hannah Snell was an amazing British woman born in 1723. She became famous for pretending to be a man so she could join the army and fight as a soldier. Her story is quite unique!

Contents

Hannah Snell's Early Life

Hannah Snell was born in Worcester, England on April 23, 1723. She was the youngest of nine children. Her father, Samuel Snell, worked as a hosier and dyer. Thanks to money from her grandfather, her family was comfortable and could afford to educate their children.

Hannah learned to read, but she never learned to write. Even as a child, people called her "young Amazon Snell." She loved to play soldier, which was a hint of her future adventures!

When Hannah was 17, her parents passed away. She moved to London in 1740 to live with her older sister, Susannah. In 1744, Hannah married James Summs, a Dutch sailor. James was not a good husband. He spent Hannah's money and left her when she was expecting their child. Sadly, their baby daughter, Susanna, died very young.

Hannah moved back in with her sister. On November 23, 1745, she made a big decision. She put on her brother-in-law's clothes, pretended to be him, and used his name, James Gray. She then went to Coventry to look for her husband. Later, she found out that James Summs had been executed for a crime.

While in Coventry, Hannah decided to join the army. She joined the 6th Regiment of Foot to fight with the Duke of Cumberland's army.

Hannah's Military Adventures

Hannah Snell's military journey began when she was 25 years old. She joined General Guise's regiment in 1757. There, she trained hard and became very good at military exercises.

During this time, she had a disagreement with a sergeant named Davis. He accused "James Gray" of not doing her duties. For this, Hannah was sentenced to a harsh punishment. She received 500 lashes while tied to a castle gate.

After this difficult event, Hannah left the army and joined the Marines. She boarded a ship called the Swallow at Portsmouth. She sailed as a cabin boy to Lisbon. Her unit was supposed to attack Mauritius, but the plan was canceled. Instead, her unit sailed to India.

In August 1748, her unit went on a mission to capture the French colony of Pondicherry in India. Later, in June 1749, she fought in a battle in Devicottail. She was wounded eleven times during her service. One bullet hit her in the groin, and five hit her leg.

After the battle, she was sent to a hospital. To keep her identity a secret, she either removed the bullet herself or got help from a local woman. This way, the army doctors would not discover she was a woman.

After three months of recovery, she rejoined her ship. Her shipmates noticed that "James Gray" never shaved. They even nicknamed her "Miss Molly Grey." To make them less suspicious, she tried to act more like a man.

Soon after, Hannah returned home to England. She was discharged from the Marines because of her wounds.

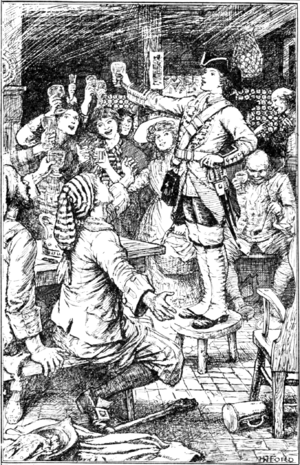

In 1750, her unit arrived back in Britain. On June 2, she bravely revealed her true identity to her shipmates in London. She then asked the Duke of Cumberland, who was the head of the army, for a pension. A pension is like a regular payment for her service.

Hannah also sold her life story to a publisher in London. It was published as The Female Soldier. She even performed on stage in her uniform, showing military drills and singing songs. Several artists painted her portrait in her uniform. The The Gentleman's Magazine also wrote about her claims.

The Royal Hospital Chelsea officially recognized Hannah's military service in November 1750. She was honorably discharged and granted a pension, which was very rare for women at that time. Her pension was even increased in 1785.

Hannah's Later Life

After getting her pension, Hannah Snell reportedly opened a pub in Wapping. It was called either The Female Warrior or The Widow in Masquerade. However, the pub did not last long.

By the mid-1750s, Hannah was living in Newbury. In 1759, she married Richard Eyles. They had two children together. In 1772, she married Richard Habgood. They moved to the Midlands. In 1785, she was living with her son, George Spence Eyles, in Stoke Newington.

In 1791, Hannah's health became unwell. She was admitted to Bethlem Royal Hospital on August 20. She passed away on February 8, 1792. She was buried at Chelsea Hospital.

Hannah Snell's Legacy

Hannah Snell's amazing life has inspired many stories. Playwright Shirley Gee wrote two plays about her: a radio play called Against the Wind (1988) and a stage play called Warrior (1989).

Hannah Snell is also mentioned in the 1969 film The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. She is described as a woman who was ready to "serve, suffer and sacrifice."

Many books have been written about Hannah's life. Her own story, The Female Sailor, was first published in 1750. You can still find her story in books today, such as:

- The Female Soldier; Or, The Surprising Life and Adventures of Hannah Snell (2011)

- The Lady Tars: The Autobiographies of Hanna Snell, Mary Lacy, Mary Talbot, and Mary Anne Talbot (2008)

- The Female Soldier: Two Accounts of Women Who Served & Fought as Men (2011)

Other books explore her life and the times she lived in. For example, Hannah Snell: The Secret Life of a Female Marine (2014) looks at the world she lived in. Female Husbands (2020) discusses how Hannah and others explored gender identity.

Hannah's story was also shared in magazines and newspapers. An early article about her appeared in London's The Gentleman's Magazine in 1750. Later in the 1800s, articles about her were published in the U.S.A. in places like The New York Ledger (1865) and The St. Paul Globe (1890). Even though her media presence slowed down in the 1900s, articles about her still appeared.

The way Hannah Snell is referred to in stories has changed over time. In her first memoir from 1746, she used her birth name, Hannah Snell, and female pronouns. But a later version in 1750 identified the author as James Gray. Many later books and articles went back to using "Hannah Snell." Most studies about her use her birth name and female pronouns. However, some newer studies, especially those looking at gender, explore her story in different ways.

See also

In Spanish: Hannah Snell para niños

In Spanish: Hannah Snell para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |