Harvard Computers facts for kids

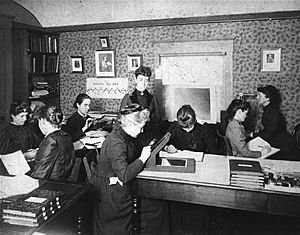

The Harvard Computers were a team of talented women who worked at the Harvard College Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. They helped process huge amounts of information about stars and space. From 1877 to 1919, Edward Charles Pickering led this team. After he passed away, Annie Jump Cannon took over.

These women were challenged to make sense of patterns in star data. They created ways to sort stars into different groups. Annie Jump Cannon became famous for her system of classifying stars, which is still used today. Antonia Maury found a way to figure out the sizes of stars from their light. Henrietta Leavitt showed how changes in certain stars could help measure distances in space.

Other important members of the team included Williamina Fleming and Florence Cushman. Even though they started mainly as "calculators," these women made big discoveries in astronomy. Many of their findings were published in scientific papers.

History of the Harvard Computers

Edward Pickering decided to hire women for this important work for a few reasons. One big reason was that men were paid much more than women. By hiring women, he could get more help with the same amount of money. This was important because there was so much star data to go through!

Even though some of these women had degrees in astronomy, they were paid like unskilled workers. They usually earned between 25 and 50 cents per hour. This was more than a factory worker but less than someone working in an office. Pickering once said that even a small delay in their work would slow down publishing results by a lot. This shows how important their careful work was.

The women often measured how bright stars were, where they were located, and their colors. They also classified stars by comparing photos to known lists. They even cleaned up images by correcting for things like how Earth's air affects light. Williamina Fleming described the work as mostly "routine work of measurement." Sometimes, women even offered to work for free just to gain experience in astronomy, a field that was hard to get into.

Amazing Women of the Harvard Computers

Mary Anna Palmer Draper's Support

Mary Anna Draper was the wife of Dr. Henry Draper, an astronomer who died before finishing his work on what stars are made of. Mary was very involved in her husband's work and wanted to finish it. She soon realized it was too big a job for one person.

Mary talked with Mr. Pickering, a close friend of hers and her husband's. Pickering offered to help finish the work and encouraged her to publish Henry's findings. In 1886, Mary Draper decided to give money and her husband's telescope to the Harvard Observatory. This was to help photograph the light of stars. She wanted to make sure her husband's work and legacy lived on. She was a loyal supporter of the observatory and a good friend to Pickering. In 1900, she even paid for a trip to see a total solar eclipse.

Williamina Fleming's Discoveries

Williamina Fleming was a Scottish immigrant who first worked as Pickering's housemaid. She had no connection to Harvard before that. Her first big task was to improve a list of star light patterns. Later, she became the head of the Henry Draper Catalogue project.

Fleming helped create a way to classify stars based on how much hydrogen they had. She also played a big part in discovering strange stars called white dwarfs. In 1899, Williamina became Harvard's Curator of Astronomical Photographs. This meant she was in charge of all the photographic plates. She was the only woman curator until the 1950s. In 1907, she became the first American woman to be chosen for the Royal Astronomical Society.

Antonia Maury's Improvements

Antonia Maury was Henry Draper's niece. Mrs. Draper recommended her, and she was hired as a computer. Antonia had graduated from Vassar College. Her job was to reclassify some stars after the Henry Draper Catalog was published.

Maury decided to go even further. She improved and redesigned the star classification system. She left the observatory for a while in 1892 and again in 1894. Pickering and the other computers helped finish her work, which was published in 1897. She returned to the observatory in 1908 as a research assistant.

Anna Winlock's Dedication

Some of the first women hired as computers had family connections to the men at the Harvard Observatory. For example, Anna Winlock was the daughter of Joseph Winlock. He was the observatory's third director and Pickering's boss before him. Anna joined the observatory in 1875 to help her family after her father's sudden death.

She took on her father's unfinished data. She did the hard math to make sense of his observations. This saved ten years' worth of numbers that would have been useless. Winlock also worked on a star cataloging section called the "Cambridge Zone." Her team worked on this project for over twenty years. Their work greatly helped create the Astronomische Gesellschaft Katalog, which has information on more than 100,000 stars. This catalog is used by observatories all over the world. Within a year of Anna Winlock starting, three other women joined the team.

Annie Jump Cannon's Star System

Pickering hired Annie Jump Cannon, who graduated from Wellesley College. Her job was to classify stars in the southern sky. At Wellesley, she learned astronomy from one of Pickering's best students, Sarah Frances Whiting. Annie became the first female assistant to study variable stars at night. She looked at how the brightness of variable stars changed over time. This helped her figure out what kind of star they were and why they varied.

Annie Jump Cannon greatly simplified the star classification system that Pickering and Williamina Fleming had started. In 1922, the International Astronomical Union officially adopted Cannon's system. This system is the basis of the O B A F G K M system we use today. It connects the color of stars to their temperature. Cannon also put variable stars into tables, making them easier to identify and compare.

Annie Jump Cannon was the first female scientist to receive many important awards and titles. She was the first woman to get an honorary doctorate from the University of Oxford. She also received the Henry Draper Medal from the National Academy of Sciences. She was the first female officer in the American Astronomical Society. Cannon later created her own award, the Annie Jump Cannon Award, for women doing advanced research in astronomy.

Henrietta Leavitt's Distance Ladder

Henrietta Swan Leavitt started working at the observatory in 1893. She had experience from college, traveling, and teaching. At Cambridge, she was excellent in math. When she began at the observatory, her job was to measure star brightness using photometry.

She found hundreds of new variable stars while studying the Great Nebula in Orion. Her work expanded to study variable stars across the whole sky with Annie Jump Cannon and Evelyn Leland. Leavitt used her photometry skills to compare stars in different photos. She studied Cepheid variables in the Small Magellanic Cloud. She discovered that how bright these stars appeared depended on how quickly they pulsed. Since all these stars were about the same distance from Earth, it meant their true brightness must also depend on their pulse period. This discovery allowed Cepheid variables to be used as "standard candles" to figure out distances in space. This led directly to our modern understanding of how big the universe truly is. Cepheid variables are still a key tool for measuring cosmic distances.

Pickering published her work, listing his name as a co-author. The discoveries Henrietta Leavitt made helped future scientists explore space even further. The famous astronomer Edwin Hubble used Leavitt's method to calculate the distance to the Andromeda Galaxy, the closest galaxy to Earth. This showed that there are many more galaxies than people had thought before.

Florence Cushman's Contributions

Florence Cushman (1860-1940) was an American astronomer at the Harvard College Observatory. She worked on the Henry Draper Catalogue.

Florence was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1860. She finished Charlestown High School in 1877. In 1888, she started working at the Harvard College Observatory for Edward Charles Pickering. Her work classifying star light patterns helped create the Henry Draper Catalogue between 1918 and 1934. She stayed as an astronomer at the Observatory until 1937 and passed away in 1940 at age 80.

Florence Cushman worked at the Harvard College Observatory for nearly 50 years. She used a method called the objective prism to study, classify, and list the light patterns of hundreds of thousands of stars. In the 1800s, photography allowed astronomers to study the night sky in much more detail than just by looking. Male astronomers at Harvard would take photos of stars on glass plates at night. During the day, female assistants like Florence would analyze these light patterns. They would calculate values, figure out brightness, and list their findings. Florence Cushman is known for figuring out the positions and brightness of the stars listed in the 1918 edition of the Henry Draper Catalogue. This book included the light patterns of about 222,000 stars.

See also

In Spanish: Computadoras de Harvard para niños

In Spanish: Computadoras de Harvard para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |