History of the wine press facts for kids

The history of the wine press is almost as old as the history of wine itself! Wine presses are special machines or tools used to squeeze juice from grapes. The very first wine presses were probably just human feet or hands, crushing grapes into a bag or container where the juice would then turn into wine.

At first, people could only squeeze a little juice out this way. So, early wines were often light in color and body. Over time, winemakers looked for better ways to press their grapes. By the time of the 18th dynasty in ancient Egypt, people were using a "sack press." This was a cloth bag filled with grapes, then twisted and squeezed using a large stick like a tourniquet.

The Bible often mentions wine presses, but these were usually large treading areas where people stomped on grapes with their feet. The juice would then flow into special basins.

The idea of a machine to extract juice from grape skins really started to grow during the ancient Greek and Roman times. Writers like Cato the Elder and Pliny the Elder described wooden wine presses. These presses used big beams, capstans (like a winch), and windlasses to push down on the leftover grape skins (called pomace). Wines made with these presses were usually darker, with more color from the skins. But they could also be a bit harsh or bitter. This type of press eventually led to the basket press, popular in the Middle Ages, and then to the modern presses used in wineries today.

Contents

Early Wine Pressing Methods

We don't know exactly when winemaking began, but many experts think it started in the area between the Black Sea and Caspian Sea. This region includes modern countries like Georgia and Armenia. Stories from around 7000 to 5000 BC describe early winemaking. People would fill hollowed-out logs with grapes, stomp on them, and then scoop the juice into jars to ferment.

The oldest clear evidence of winemaking comes from a site called Areni-1 winery in Armenia, dating back to about 4000 BC. This site had a trough (a long, narrow container) with a drain leading to a vat that could hold about 14–15 gallons (52–57 liters) of wine. While these findings show wine was made, they don't always show exactly how the grapes were pressed.

In ancient Egypt, people likely used their feet to crush grapes. However, tomb paintings from Thebes show that Egyptians made some improvements. They used long bars hanging over the treading basins and straps for workers to hold onto while stomping.

By the 18th Dynasty (around 1550 – 1292 BC), Egyptians were also using a "sack press." Grapes or leftover skins from treading would be put into a cloth sack. Then, the sack was twisted and squeezed using a stick to get more juice out. A different version of this sack press involved hanging the sack between two large poles. Workers would walk in opposite directions, squeezing the grapes in the bag. The juice would collect in a vat below. This early press not only squeezed more juice but also helped filter the wine through the cloth.

Greek and Roman Innovations

One of the earliest known Greek wine presses was found in Palekastro, Crete, from the Mycenaean period (1600–1100 BC). Like many early presses, it was a stone basin where grapes were stomped, with a drain for the juice. Later, some winemakers in Crete would lay grapes under wooden planks and weigh them down with rocks to press out the juice, similar to how olive oil was made.

The wine made from these simple presses wasn't highly valued by the Greeks. It often had impurities and didn't last long. The most prized wine came from "free run" juice. This was the juice that flowed out from the grapes just from their own weight, before any stomping or pressing. This wine was thought to be the purest and was often used for medicine.

In the 2nd century BC, the Roman writer Cato the Elder described how to build a Roman wine press in his book De Agri Cultura. This press was called a lever or beam press. It had a large horizontal beam held up by upright posts. Grapes were placed under the beam, and pressure was applied by a windlass (a type of crank) that pulled down one end of the beam with ropes.

In the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder described a "Greek style" press where the windlass was replaced by a vertical screw. Other Roman writers also described wine presses. Even though they are mentioned often in ancient writings and found at archaeological sites, wine presses were actually quite rare. They were very expensive and large, so most Roman farmers couldn't afford them. Instead, it was more common for Roman estates to have large tanks where grapes were stomped by feet or paddles.

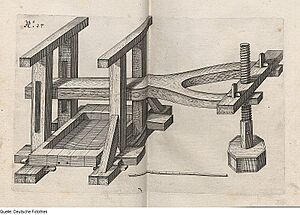

By the 2nd century AD, the Romans started using a "screw press," which was a step towards the basket press that became popular later. This press had a large beam with a screw in the middle. A heavy stone was attached to the bottom of the beam. The stone fit into a vat lined with porous clay or cloth. Workers would turn the screw, causing the stone to press down on the grapes, squeezing out the juice. This juice would drain into buckets and then into large fermentation vessels.

Medieval Basket Presses

During the Middle Ages, many advances in winemaking were made by religious orders, especially in France and Germany. These groups owned huge vineyards and made a lot of wine in their abbeys. This is when the basket press became popular.

The basket press had a large, round basket made of wooden slats held together by rings. A heavy, flat disc was placed on top. After grapes were loaded into the basket, the disc would be pushed down. Juice would seep out between the wooden slats into a basin below. Some presses used a giant lever or a hand crank to add more pressure.

While the basket press became common for Church-owned estates, many small farmers in Europe still stomped grapes in stone basins. However, church records show that local farmers were often willing to pay a part of their crop to use a landlord's wine press if one was available. This was probably because pressing could produce 15% to 20% more wine than treading. Also, it was safer. Records from that time show that workers sometimes got sick or passed out from the carbon dioxide gas released while stomping fermenting grapes in a vat.

Different Qualities of Juice

As the basket press became more popular, winemakers started to notice that different levels of pressing produced different qualities of wine. The best quality was called vin de goutte (meaning "drop wine"). This was the "free run" juice that came out just from the weight of the grapes themselves as they were loaded into the press. This juice was usually the lightest in color and body.

The juice that came from pressing was called vin de presse. It was darker and had more tannins (which can make wine taste bitter or dry). Sometimes, these different juices were kept separate.

In the Champagne wine region, they were very careful about how they pressed grapes for Champagne. A famous monk named Dom Pérignon (around 1700) set rules for pressing. He said pressing should happen quickly after harvest to keep the juice fresh and prevent red grapes from coloring the juice too much. The free run juice was sometimes not used for fine Champagne because it was too delicate. The first and second pressings were considered ideal for sparkling wine production. Later pressings were often too harsh or colored for Champagne.

Changing Wine Styles

In the 17th and 18th centuries, French winemaking started to focus on stronger wines that could age well and survive long journeys overseas. Winemaking books began to suggest that all good winemakers should use a wine press. Sometimes, blending in a little of the pressed wine was important to add color and body, helping the wine last longer.

Even in Bordeaux, where people still used treading basins long after other French regions adopted the basket press, the wine press became more popular. This happened after the dark, full-bodied wines from Ho-Bryan became very famous in England. By the late 1700s, almost all important Bordeaux wineries were using a similar method: letting grapes ferment longer in the vat and then pressing the darker juice into new oak barrels.

The invention of steam power in the 19th century completely changed wine press technology. Manual basket presses were replaced by steam-powered presses. These new machines made pressing much more efficient and required less human effort. Even the growth of rail transport helped, as it became cheaper to move large wine presses from factories to wineries around the world.

Modern Wine Presses

With some improvements, the basket press has continued to be used for centuries by both small, artisan winemakers and large Champagne houses. In Europe, you can still find basket presses with hydraulic machinery in places like Sauternes and Burgundy.

In the 20th century, wine presses evolved from vertical pressing (like the basket press) to horizontal pressing. Pressure could be applied from one or both ends, or from the side using an airbag or bladder. These new presses were either "batch" presses, which had to be emptied and refilled like a basket press, or "continuous" presses. Continuous presses would constantly move grapes through, applying more and more pressure, with new grapes added and pressed skins removed all the time.

Another big step for horizontal batch presses was making them completely enclosed (sometimes called "tank presses"). This stopped the grape juice from touching too much air. Some advanced presses can even be filled with nitrogen gas to create an environment with no oxygen, which is good for making certain white wines. Plus, many modern presses are controlled by computers. This lets the operator precisely control how much pressure is put on the grape skins and for how many cycles.

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |