Eyrewell ground beetle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Eyrewell ground beetle |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

Nationally Critical (NZ TCS) |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: |

Harpalinae

|

| Genus: |

Holcaspis

|

| Species: |

H. brevicula

|

| Binomial name | |

| Holcaspis brevicula Butcher, 1984

|

|

The Holcaspis brevicula, also known as the Eyrewell ground beetle, is a very rare beetle. It lives only in New Zealand. This small, black beetle cannot fly. It belongs to a group of beetles called Holcaspis. These beetles live in the dry, eastern lowlands of New Zealand's South Island.

The Eyrewell ground beetle is critically endangered. This means it is at a very high risk of dying out. Only ten of these beetles have ever been found. They all came from Eyrewell Forest. This forest was a plantation of pine trees. Now, much of it is being turned into dairy farms.

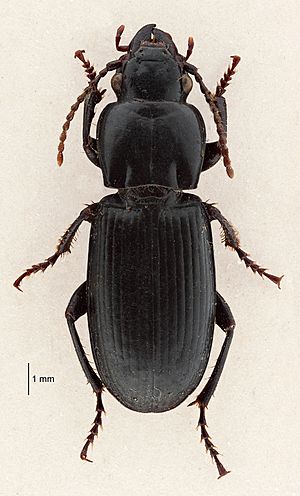

What Does the Eyrewell Ground Beetle Look Like?

Michael Butcher first described the H. brevicula in 1984. At that time, only two male beetles were known. They were found in Eyrewell Forest in 1961.

This beetle is small, about 10–11 mm long. It has a shiny black body. It cannot fly. The H. brevicula is a predator. This means it hunts and eats other small creatures. It is probably active at night.

Scientists can tell H. brevicula apart from its close relative, H. algida. They look at the patterns of tiny holes and hairs on its body. They also check the male beetle's shorter aedeagus (a part of its body). Since adult beetles have been found in winter, they likely live for more than two years. This is quite a long time for a beetle.

Where Does the Eyrewell Ground Beetle Live?

Eyrewell Forest has dry, stony soil. The land drains water very quickly. Originally, this area was covered in kānuka (Kunzea serotina) shrubs and forests. Some tōtara (Podocarpus totara) trees also grew there.

Over time, Māori and European settlers burned much of this native habitat. Now, only small pieces of kānuka forest remain. These pieces are less than 20 hectares in size. Some are protected on private land. The Eyrewell Scientific Reserve is a small protected area. It is managed by the Department of Conservation.

The poor soil at Eyrewell was not good for farming crops. So, it was mostly used for sheep farming. Between 1928 and 1932, the native mānuka forest was cleared. Then, a large plantation of Monterey pine trees was planted. This plantation, called Eyrewell Forest, covered 6764 hectares.

The area has been used for pine tree farming ever since. Blocks of trees are cut down and replanted every 27 years. Some older areas of the forest had native shrubs and mosses growing underneath the pines. This happened even with regular tree cutting.

The Holcaspis brevicula lived in the kānuka forest. It stayed even after pine trees were planted. It has continued to live in the pine plantation. However, it has disappeared from the small pieces of native kānuka forest nearby. These areas seem too small and damaged to support the beetle.

Scientists searched for the beetle between 2000 and 2005. They used special traps. They spent a lot of time searching, over 57,000 "trap days." They found five more H. brevicula beetles. All of them were in the pine forest. Three more beetles were found in an insect collection. These were collected between 1956 and 1967. All ten known beetles have come from Eyrewell Forest. This means it is the only known place where this beetle lives.

Saving the Eyrewell Ground Beetle

Because it is so rare and lives in only one place, H. brevicula is "nationally critical." This means it is in extreme danger of becoming extinct. The Department of Conservation chose it as a top priority species in 2017.

Sadly, this beetle has no special legal protection. In New Zealand, private forest land can be cut down. This can happen even if it is the only home for an endangered species.

In recent years, farming in the Canterbury Plains has changed. Farmers are now using irrigation for dairy farming. This is more profitable than traditional farming or forestry. Eyrewell Forest was once government land. It was bought from the Ngāi Tahu people in 1848.

In 2000, Eyrewell Forest was returned to Ngāi Tūāhuriri. This is a subtribe of Ngāi Tahu. This was part of a settlement for past land claims. Ngāi Tahu Farming then planned to turn part of the forest into dairy farms. This area is now called Te Whenua Hou.

More farms were set up as forestry permits ended. In 2016, it was announced that Eyrewell Forest would be completely cleared. It would become 8,500 hectares of irrigated pasture. This land would support 14,000 dairy cows. Most of the forest was cleared by 2017/2018.

By January 2019, almost all of Eyrewell Forest was gone. Satellite images show this change. Clearing the forest involved cutting down all the trees. Then, the roots were pulled out. The remaining wood was mulched into small chips. This process destroyed not only plants but also any insects larger than a pinhead.

Documents show that the Department of Conservation could not agree with Ngāi Tahu Farming. They could not save enough beetle habitat. Forest and Bird group criticized the dairy farm plan. They said it would lead to the extinction of H. brevicula.

Ngāi Tahu responded that they would plant 150 hectares of native shrubs. This would replace the 6700 hectares of pine forest. They would also plant more native plants around farms. However, the beetle does not live in the remaining native forest. So, it is not clear if it would move into these new plantings. The planting project has not been very successful. Trees were planted in dry fields. They were also exposed to too much fertilizer runoff from cow pastures.

- Areas marked as “indigenous vegetation restoration” on Ngāi Tahu Farming plans

Lincoln University has been checking the remaining forest since 2013. They have not found any Eyrewell beetles. These surveys will continue until 2020. Scientists have criticized the decision to convert the forest to dairy farms. They said it was based on money, not on protecting nature. If Ngāi Tahu Farming does not restore kānuka forest, the beetle could soon be extinct. In November 2018, the lead scientist said he was thinking of writing the beetle's "obituary." This means he thought it might be too late to save it.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |