Jack Sheppard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jack Sheppard

|

|

|---|---|

A sketch of Jack Sheppard in Newgate Prison, around 1723.

|

|

| Born | 4 March 1702 Spitalfields, Middlesex, England

|

| Died | 16 November 1724 (aged 22) |

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Nationality | English |

| Other names | "Gentleman Jack", "Jack the Lad", "Honest Jack" |

| Occupation | carpenter, thief, prison escapee |

| Known for | his many escapes from prison and his crimes of theft. |

John "Jack" Sheppard (born March 4, 1702 – died November 16, 1724) was a famous English thief and prison escapee in London during the early 1700s. He was also known as "Honest Jack."

Jack was born into a poor family. He started learning to be a carpenter, but before he finished his training, he began stealing in 1723. In 1724, he was arrested and put in prison five times. Amazingly, he managed to escape from prison four times! This made him very famous, especially among poorer people. However, he was eventually caught, found guilty, and executed at Tyburn. His short life of crime lasted less than two years.

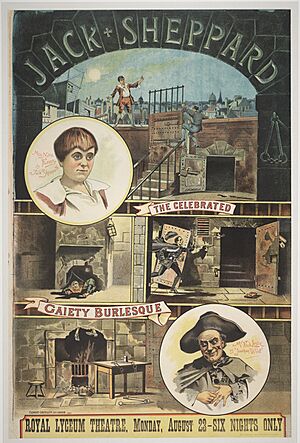

Sheppard became well-known for his clever prison escapes. A story about his life, called a "Narrative," was sold when he was executed. Many people believe the famous writer Daniel Defoe secretly wrote it. Soon after, popular plays about Jack Sheppard were created.

The character of Captain Macheath in John Gay's famous play The Beggar's Opera (1728) was based on Jack Sheppard. This helped keep his story alive for over 100 years. He became popular again around 1840 when William Harrison Ainsworth wrote a novel called Jack Sheppard. This book had pictures by George Cruikshank. People were so interested in his story that authorities worried others might try to copy him. Because of this, they banned any plays in London with "Jack Sheppard" in the title for forty years.

Contents

Jack Sheppard's Story in Culture

People reacted strongly to Jack Sheppard's adventures. Newspapers often wrote about his deeds. Many pamphlets, songs, and stories were made about his real and imagined experiences. His story was quickly turned into plays. For example, Harlequin Sheppard, a pantomime play, opened just two weeks after Jack was executed.

His life story remained well-known through a book called the Newgate Calendar. A play called The Prison-Breaker was never performed but was later turned into The Quaker's Opera. This play was shown at the Bartholomew Fair. People even wrote imaginary conversations, like one between Jack Sheppard and Julius Caesar, where Sheppard compared his adventures to Caesar's.

One of the most famous plays inspired by Sheppard was John Gay's The Beggar's Opera (1728). Jack Sheppard was the main inspiration for the character Captain Macheath. This play was incredibly popular and was performed regularly for over a century. Two hundred years later, The Beggar's Opera inspired The Threepenny Opera by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill (1928).

Jack Sheppard's story might have also inspired William Hogarth's 1747 series of pictures called Industry and Idleness. These pictures show two apprentices: Tom Idle, who turns to crime and is executed, and Francis Goodchild, who works hard, becomes successful, and even becomes the Lord Mayor of London.

Sheppard's tale became popular again in the early 1800s. A play called Jack Sheppard, The Housebreaker, or London in 1724 was published in 1825. Even more successful was William Harrison Ainsworth's novel, also titled Jack Sheppard. It was published in a magazine starting in 1839, with pictures by George Cruikshank. This novel showed Jack as a brave hero. Cruikshank's pictures were so good that some people said he "created the tale."

The novel quickly became very popular. It was even published as a book before the magazine series finished. Ainsworth's novel was also made into a successful play in 1839. This story created a huge cultural excitement, with many pamphlets, pictures, cartoons, plays, and souvenirs. A popular song from the play, "Nix My Dolly, Pals, Fake Away," was heard everywhere in the streets.

Because of public concern that young people might try to copy Sheppard, the government banned plays with "Jack Sheppard" in the title for forty years in London. After the ban ended, new versions of the story appeared, including a popular play called Little Jack Sheppard (1886).

Jack Sheppard in Modern Times

Jack Sheppard's story has been made into movies three times in the 20th century: The Hairbreadth Escape of Jack Sheppard (1900), Jack Sheppard (1923), and Where's Jack? (1969). The 1969 film was a British drama directed by James Clavell, starring Tommy Steele as Jack.

In 2017, Jake Arnott included Jack Sheppard in his novel The Fatal Tree.

In 1971, the British music group Chicory Tip released a song called "Don't Hang Jack." The song tells Jack's story from the view of someone in the courtroom. It describes his daring acts as a thief and asks the judge to spare him because he was loved by women and admired by young men.

Why Jack Sheppard is Remembered

Many people have wondered why Jack Sheppard's story has stayed popular for so long. Some suggest that his legend is about the idea of escaping from being locked up. In the past, many people were put away in institutions. Sheppard's escapes showed a way out of this "Great Confinement."

Others believe that the laws applied to working-class criminals like Sheppard were a way to control people. These laws made them accept stricter property rules. Another idea from the 1800s, shared by Charles Mackay, explains why people admire famous thieves:

Whether it be that the multitude, feeling the pangs of poverty, sympathise with the daring and ingenious depredators who take away the rich man's superfluity, or whether it be the interest that mankind in general feel for the records of perilous adventure, it is certain that the populace of all countries look with admiration upon great and successful thieves.

This means that people, especially those who are poor, might admire clever thieves who take from the rich. Or, it could be that people just enjoy exciting stories of dangerous adventures.

See also

In Spanish: Jack Sheppard para niños

In Spanish: Jack Sheppard para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |