James Braid (surgeon) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Braid

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 19 June 1795 Portmoak, Kinross-shire, Scotland

|

| Died | 25 March 1860 (aged 64) Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, England

|

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Known for |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Influences | Thomas Brown, Charles Lafontaine |

| Influenced |

|

James Braid (born June 19, 1795 – died March 25, 1860) was a Scottish surgeon and a scientist who studied nature. He was also known as a "gentleman scientist" because he worked independently.

Braid made important discoveries in treating physical conditions like clubfoot (a foot deformity), spinal curvature (curved spine), knock-knees, bandy legs, and squint (crossed eyes). He was also a major pioneer in using hypnotism and hypnotherapy (using hypnosis for treatment). He helped introduce both hypnotic pain relief and chemical pain relief (like anesthesia) for surgeries. Some people, like Kroger (2008), call him the "Father of Modern Hypnotism." However, others, like Weitzenhoffer (2000), suggest being careful about saying his "hypnotism" is exactly the same as what is practiced today.

Contents

- Early Life and Family

- Education and Training

- A Skilled Surgeon

- Groups and Societies James Braid Joined

- Discovering Hypnotism

- Challenging False Claims

- Sharing His Discoveries

- New Words for a New Science

- How Hypnotism Was Induced

- The Power of Ideas

- Later Life and Death

- His Lasting Influence

- His Writings

- John Milne Bramwell: Keeping Braid's Work Alive

- The James Braid Society

- See also

Early Life and Family

James Braid was born on June 19, 1795, in Portmoak, Kinross, Scotland. He was the third son and the youngest of seven children of James Braid and Anne Suttie.

When he was 18, on November 17, 1813, Braid married Margaret Mason. They had two children, Anne Daniel and James Braid, both born in Leadhills, Scotland.

Education and Training

Braid learned surgery by working as an apprentice for Thomas and Charles Anderson in Leith. During this time, from 1812 to 1814, he also attended the University of Edinburgh. There, he was influenced by Thomas Brown, a philosophy professor.

In 1815, Braid earned his diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. This allowed him to practice as a surgeon.

A Skilled Surgeon

In 1816, Braid became the surgeon for Lord Hopetoun's mines in Leadhills. In 1825, he started his own private practice in Dumfries. There, he met another skilled surgeon, William Maxwell.

One of his patients, Alexander Petty, invited Braid to move his practice to Manchester, England. Braid moved to Manchester in 1828 and worked there until he died in 1860.

Braid was a highly respected and successful surgeon. Even though he became famous for hypnotism, he was also known for his successful operations on deformities. By 1841, he had performed surgery on many cases of clubfoot, crossed eyes, and spinal curvature.

Groups and Societies James Braid Joined

Braid was a member of several important scientific and educational groups. These included the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and the Provincial Medical and Surgical Association. He was also a corresponding member of the Wernerian Natural History Society of Edinburgh and the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh. He was a member of the Manchester Athenaeum and an honorary curator at the Manchester Natural History Society museum.

Discovering Hypnotism

From Mesmerism to Hypnotism

Braid first saw "animal magnetism" (also called mesmerism) at a public show by a French performer named Charles Lafontaine. This happened at the Manchester Athenæum on November 13, 1841.

Before this, Braid believed that animal magnetism was not real. He thought it was just people imagining things or being influenced by others. He had read articles that said there was no evidence of any "magnetic force" causing these effects. He also knew about cases where people faked symptoms.

However, when he saw Lafontaine's show, one thing caught his attention: a patient could not open their eyelids. Braid was convinced this was real and not just imagination. He decided to do his own experiments to find out more.

Braid always said he went to Lafontaine's show with an open mind. He wanted to see the evidence for himself, not just rely on what he had heard or read. He wasn't trying to prove Lafontaine wrong, nor was he blindly believing him.

Braid was one of the doctors invited to examine Lafontaine's subjects. He noticed that their physical state was truly different. Braid believed that while the effects were real, they were not caused by any "magnetic force" as Lafontaine claimed. He also disagreed that the changes came from another person's influence.

Braid's Own Experiments

Braid then did his own important experiment. He believed in Occam's razor, which means finding the simplest explanation. Instead of thinking the operator had a special power, he thought the process came from within the subject, guided by the operator. Braid proved this by experimenting on himself. He used what he called an "upwards and inwards squint."

Braid's success with self-hypnotism showed that it didn't need any special "gaze," "charisma," or "magnetism" from the operator. All it needed was for a person to focus their eyes on an object at a certain height and distance. This would create the "upwards and inwards squint." By doing this on himself, Braid also proved that Lafontaine's effects were not due to any magnetic force.

Self-Hypnotism and Guiding Others

Braid did many experiments on himself. He became convinced that he had found the natural way the body and mind work together to create these effects. On November 22, 1841, he performed his first guided hypnotism on another person, Mr. J. A. Walker, at his home with several witnesses.

The following Saturday, November 27, 1841, Braid gave his first public lecture. He showed that he could create the same effects as Lafontaine without touching the subject at all.

Challenging False Claims

On April 10, 1842, a religious leader named Hugh Boyd M‘Neile gave a long sermon against mesmerism. He claimed that mesmerism was caused by "satanic agency" (the devil's work). He attacked Braid personally and professionally, saying Braid's work was linked to evil and had no real medical use.

Braid learned about these claims from newspaper reports. He sent a polite letter to M‘Neile, explaining his work and inviting him to his lecture. However, M‘Neile did not reply or attend. He even published his sermon without any changes. This forced Braid to publish his own response in a pamphlet on June 4, 1842. This pamphlet is considered very important in the history of hypnotism.

Sharing His Discoveries

Braid wrote a report called "Practical Essay on the Curative Agency of Neuro-Hypnotism." He tried to have it presented at the British Science Association in June 1842. Although it was first accepted, it was later rejected. So, Braid held his own meetings to share his findings.

He explained his view compared to others:

- Some people thought mesmerism was a trick.

- Others believed it was real but caused by imagination or imitation.

- Animal magnetists thought a magnetic force was involved.

- Braid's view was that the effects came from a special state of the brain and spinal cord.

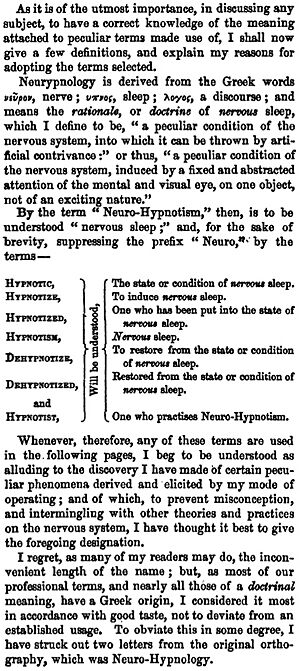

New Words for a New Science

By February 1842, Braid started using the term "Neurohypnology," which he later shortened to "Neurypnology." In a public lecture on March 12, 1842, he explained why he chose these words:

He wanted a new name instead of "animal magnetism." He chose "neurohypnology" because it means "the study of nervous sleep." He used "sleep" as a metaphor because it was similar to the state people entered. He also introduced "hypnotism" instead of "magnetism" or "mesmerism," and "hypnotised" instead of "magnetised" or "mesmerised."

It's important to know that:

- Braid used "sleep" as a comparison, not literally.

- Braid himself never used the exact term "hypnosis."

- The word "hypnosis" came later, in the 1880s.

Braid was the first to use "hypnotism," "hypnotise," and "hypnotist" in English. He used them in a modern way, referring to a scientific theory about the mind and body, not a magical or "occult" one.

In 1845, Braid wrote that he used "hypnotism" to show that his work was different from those who believed in magnetic fluids or outside influences. He clearly stated that hypnotism's effects could be explained by "physiological and psychological principles." He also said he didn't believe it was just imagination. Instead, he thought it was caused by intense focus and concentration.

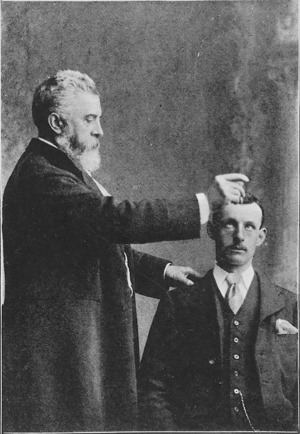

How Hypnotism Was Induced

Braid emphasized that to induce hypnotism, a person needed to focus both their eyes and their thoughts. He called this "the continued fixation of the mental and visual eye." He believed this engaged a natural body mechanism.

He explained that by focusing your mind and eyes on a non-exciting object, staying still, and allowing yourself to feel sleepy, you could enter a state of "nervous sleep." In this state, the brain and nervous system become more open to suggestions. Braid believed this was a natural law of the body.

In 1843, Braid published his main book, Neurypnology; or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep. This book explained his ideas in detail. It was very popular, selling 800 copies quickly.

Braid saw hypnotism as a "nervous sleep" different from regular sleep. He found the best way to create it was by having someone stare at a small, bright object held about eighteen inches in front of their eyes. He thought this strained the eye muscles and caused the hypnotic state.

He completely rejected the idea that a magnetic fluid caused hypnotic events. He showed that anyone could produce these effects in themselves by following his simple rules.

The Power of Ideas

Braid's friend and colleague, William Benjamin Carpenter, presented an important paper in 1852. He explained that the effects of Braid's hypnotism came from a person focusing on a single, strong idea. This idea would then influence the body's actions. Carpenter said it wasn't the operator's "will" controlling the subject, but the operator's "suggestion" creating an "idea" in the subject's mind. This suggested idea could cause movements and other body changes without the person trying to make them happen.

Carpenter called this the "ideo-motor principle of action." Braid quickly adopted this idea. To show the importance of a single, strong idea, Braid called it the "mono-ideo-dynamic principle of action."

Later Life and Death

Braid remained very interested in hypnotism until he died. Just three days before his death, he sent a manuscript about hypnotism to a French surgeon, Étienne Eugène Azam.

James Braid died on March 25, 1860, in Manchester, after a short illness. Some reports say he died from a stroke, others from heart disease. He was survived by his wife, his son James, and his daughter.

His Lasting Influence

Braid's work greatly influenced many important French doctors, including Étienne Eugène Azam, Paul Broca, Joseph Pierre Durand de Gros, and Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault. Liébeault was a co-founder of the famous Nancy School of hypnotism.

In England, James Braid's legacy was mainly continued by John Milne Bramwell. Bramwell collected all of Braid's available works and wrote a biography about him. He also wrote several books on hypnotism himself.

His Writings

Braid published many letters and articles in journals and newspapers. He also wrote several pamphlets and books, often combining his earlier published works.

His first major book was Neurypnology, or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep (1843). He wrote this less than two years after discovering hypnotism.

He kept changing his theories and how he used hypnotism in his practice, based on his experiments and experience. Six weeks before he died, Braid wrote that he had been using hypnotism daily for 19 years. In his last published letter, written four weeks before his death, he said his experiments showed that all the effects of hypnotism came from "influences residing entirely within, and not without, the patient's own body."

In 2009, a reconstructed English version of Braid's last lost manuscript, On Hypnotism, was published.

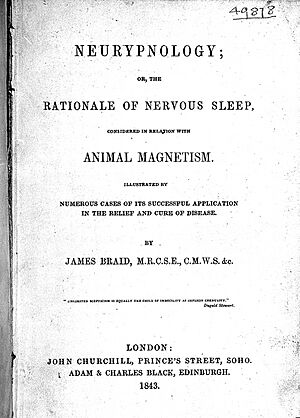

John Milne Bramwell: Keeping Braid's Work Alive

John Milne Bramwell was a skilled medical hypnotist and hypnotherapist. He studied Braid's work deeply and helped keep Braid's legacy alive in Great Britain.

Bramwell had studied medicine at Edinburgh University at the same time as Braid's grandson, Charles. Because of his studies and his connection to Charles Braid, Bramwell had access to many of Braid's writings and papers.

In 1896, Bramwell noted that Braid's name was well-known to students of hypnotism. They often gave him credit for saving the science from misunderstanding and old beliefs. However, Bramwell found that many students thought Braid had wrong ideas that later research had disproved.

Bramwell realized that few people knew Braid's other works besides Neurypnology. They didn't know that Braid's views had changed in his later writings. Bramwell also found three common mistakes about Braid:

- People thought Braid was English (he was Scottish).

- They believed he supported phrenology (he did not).

- They thought he knew nothing about suggestion (he was actually a strong supporter of it and was the first to use the term "suggestion" in this context).

Bramwell wrote about Braid's work in a French hypnotism journal in 1897. He strongly emphasized Braid's importance. When another expert, Bernheim, mistakenly said Braid knew nothing of suggestion, Bramwell responded firmly. He provided quotes from Braid's writings that clearly showed Braid used suggestion intelligently and had a clearer understanding of it than many others at the time.

The James Braid Society

In 1997, a group called the James Braid Society was created. This group recognizes Braid's role in developing hypnosis for therapy. It is a discussion group for people who use hypnosis ethically. The society meets monthly in London for presentations on hypnotherapy.

|

See also

In Spanish: James Braid para niños

In Spanish: James Braid para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |