Paul Broca facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paul Broca

|

|

|---|---|

Pierre Paul Broca

|

|

| Born | 28 June 1824 |

| Died | 9 July 1880 (aged 56) Paris, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anthropology, anatomy, medicine |

Pierre Paul Broca (born June 28, 1824 – died July 9, 1880) was a French doctor, anatomist, and anthropologist. He is most famous for his research on a part of the brain called Broca's area. This area is named after him.

Broca's area is found in the front part of the brain. It is very important for speaking and language. His work showed that people who had trouble speaking (a condition called aphasia) had damage in this specific part of their brain. This was a big step in proving that different parts of the brain have different jobs.

Broca also helped develop physical anthropology. This field studies human physical features. He worked on measuring human bodies and skulls, a science called anthropometry and craniometry. However, some of his ideas about using these measurements to rank human groups are now seen as wrong and harmful. He also studied the differences between humans and apes.

Contents

Paul Broca's Life Story

Paul Broca was born on June 28, 1824, in a town called Sainte-Foy-la-Grande in France. His father, Jean Pierre Broca, was a doctor. His mother, Annette Thomas, was the daughter of a preacher.

Broca went to school in his hometown. He earned his first degree at age 16. He then went to medical school in Paris when he was 17. He finished his medical studies at 20, which was very young for that time.

Becoming a Doctor and Researcher

After medical school, Broca worked as an intern with famous doctors. In 1848, he became a Prosector at the University of Paris Medical School. This meant he prepared bodies for anatomy lessons. He earned his medical doctorate in 1849.

By 1853, Broca became a professor and a hospital surgeon. He later became a professor of surgery. He was also elected to the Académie Nationale de Médecine, a famous medical academy. He worked in several hospitals in Paris.

Broca was also a very active researcher. He joined the Society Anatomique de Paris in 1847. He was one of its most active members. He also joined the Société de Biologie and later became president of the Societe de Chirurgie.

Broca's Beliefs and Family Life

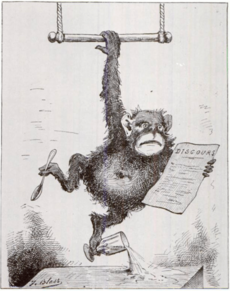

In 1848, Broca started a group for people who thought freely. They were interested in Charles Darwin's ideas about evolution. Broca once said he would rather be "a transformed ape than a degenerate son of Adam." This caused problems with the church, which did not like his ideas.

In 1857, Broca married Adele Augustine Lugol. She came from a Protestant family. They had three children: Jeanne, Benjamin, and Élie.

Broca continued his scientific work. In 1859, he started the Society of Anthropology of Paris. He also started a journal and an institute for anthropology. The French Church tried to stop the teaching of anthropology.

Near the end of his life, Paul Broca became a senator for life in France. He died on July 9, 1880, at age 56. His sons, Auguste and André, also became doctors.

Early Medical Discoveries

Broca made many contributions to medical science. He often presented his findings at the Society Anatomique de Paris.

He showed that rickets, a bone disorder in children, was caused by poor nutrition. He also studied osteoarthritis, a joint disease. Broca explained how cartilage in joints breaks down. He also researched clubfoot, a birth defect. His work helped understand muscle diseases like muscular dystrophy.

As a surgeon, Broca studied the use of chloroform for anesthesia. He also tried using hypnosis to manage pain during surgery. He wrote a long book about aneurysms, which are weakened blood vessels. This book made him well-known among French doctors.

Broca also worked with Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard on the nervous system. They showed how nerves cross in the brain. This means the right side of the brain controls the left side of the body, and vice versa.

Broca also studied cancer. He thought that some cancers might be passed down in families. He also believed that cancer cells could travel through the blood. Many scientists were unsure about his ideas at the time.

Understanding Human Groups

Broca spent a lot of time at his Anthropological Institute. He studied human skulls and bones. He tried to use these measurements to rank different human groups. This part of his work is now called 'scientific racism' and is not supported today.

He helped create new tools and ways to measure human features. He wrote many papers on anthropology. He founded the Société d'Anthropologie de Paris in 1859.

Broca defined anthropology as "the study of the human group, considered as a whole." He believed in using science to understand human origins. He did not rely on religious texts for his scientific work.

Ideas About Human Species

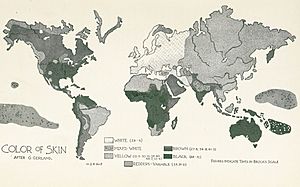

Broca believed that different human groups came from different origins. This idea is called polygenism. He thought that each group had its own place on a scale from 'barbarism' to 'civilization'. He used this idea to justify European colonization.

In his 1859 book, On the Phenomenon of Hybridity in the Genus Homo, he said humanity was made of different groups. These included Australian, Caucasian, Mongolian, Malayan, Ethiopian (Negro), and American groups. He thought each group was its own species. These different species together formed the single genus homo.

Broca believed his ideas were based on scientific evidence. He also thought that the environment did not change physical traits over long periods. For example, he said Jewish people looked the same as in ancient Egyptian paintings.

Mixed Groups

Broca used the idea of hybridity to argue against the idea that all humans came from one ancestor. He said that different groups being able to have children together did not prove they were the same species.

He looked at how different groups mixed. He thought that mixing between different racial groups could lead to problems. He believed that children from such mixing might become less able over generations. These ideas are now considered incorrect and harmful.

Measuring Skulls

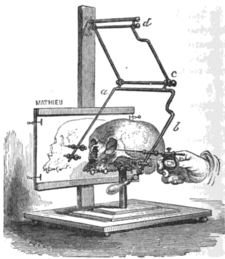

Broca is known for his work in anthropometry. This is the scientific measurement of human physical features. He created many tools and ways to measure skulls, called craniometry.

He believed that the size and shape of the brain were important for intelligence. He thought that Europeans had larger frontal brain areas than other groups. However, he later realized that larger skulls were not always linked to higher intelligence. He still thought brain size was important for social progress and education.

Broca also developed ways to measure eye, skin, and hair color. These methods were designed to be used in the field.

Evolutionary Ideas

Broca accepted evolution as a way to explain how species change. However, he did not think Darwin's theory fully explained everything. He believed there might be other processes that worked alongside evolution.

He eventually changed his mind about polygenism for humans. He agreed that all human groups came from a single origin.

Understanding Language

Broca's Area and Speech

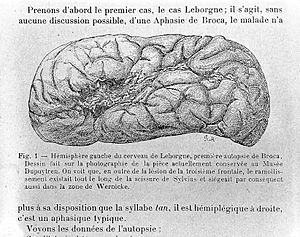

Broca is famous for his theory that the part of the brain for speaking is on the left side. He found this area in the front part of the brain, now called Broca's area. He made this discovery by studying patients who had trouble speaking.

This research started because of a debate. Some scientists believed different parts of the brain had different jobs. Others thought the brain worked as a whole. Broca's work helped settle this debate.

In 1861, Broca met a patient named Louis Victor Leborgne. This patient had lost the ability to speak clearly for 21 years. He could only say the word "tan." Broca performed an autopsy after Leborgne died. He found damage in the left front part of Leborgne's brain. This area was next to the lateral sulcus. Broca believed this damage explained why Leborgne could not speak.

Broca found a second patient, Lazare Lelong, with similar damage. Lelong could only say five words. After Lelong died, Broca found damage in the same brain area. These findings convinced Broca that a specific brain area controlled speech. Over the next two years, he found similar evidence in 12 more cases.

Broca published his findings in 1865. His work encouraged other scientists to link brain regions to specific functions. Another doctor, Marc Dax, had made similar observations earlier. However, Dax's work was not published until after Broca's discoveries.

More than 100 years later, scientists re-examined Leborgne's and Lelong's brains using modern MRI technology. They found that the damage was more widespread than Broca could see. The lesions went deeper into the brain.

The brains of many of Broca's patients are still kept at the Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris.

Patients with damage to Broca's area often have Expressive aphasia (also called Broca's aphasia). This means they have trouble speaking. This is different from receptive aphasia (Wernicke's aphasia), where people have trouble understanding language. Wernicke's aphasia is caused by damage to a different part of the brain.

Criticism and Legacy

Views on Race and Science

Broca was one of the first anthropologists to compare the anatomy of humans and apes. He suggested that people of African descent were a middle form between apes and Europeans. The scientist Stephen Jay Gould criticized Broca for this. Gould said Broca and others were involved in "scientific racism." This means they used science to support ideas that some human groups were better than others. These ideas are now widely rejected.

Broca's Lasting Impact

The discovery of Broca's area changed how we understand language. It helped us learn how we produce speech and understand it. Broca's work was key in showing that different brain parts have different jobs. His research also led others to find other important brain areas, like Wernicke's area.

New research shows that problems in Broca's area can cause other speech issues. These include stuttering and apraxia of speech.

Broca also invented more than 20 tools for measuring skulls. He helped create standard ways to measure human features.

His name is one of the 72 names written on the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Selected Writings

- 1856. Des anévrysmes et de leur traitement. (On Aneurysms and their Treatment)

- 1861. "Remarques sur le siège de la faculté du langage articulé, suivies d'une observation d'aphémie." (Notes on the location of the faculty of articulated language, followed by an observation of aphasia)

- 1864. On the phenomena of hybridity in the genus Homo. (On the phenomena of hybridity in the human genus)

- 1865. "Sur le siège de la faculté du langage articulé." (On the location of the faculty of articulated language)

More to Explore

In Spanish: Paul Broca para niños

In Spanish: Paul Broca para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |