History of anthropometry facts for kids

The history of anthropometry is about how people have measured the human body over time. It was first used in anthropology to study human groups. People also used it for identification, to understand how human bodies differ, and even to try and link physical traits to different groups of people or their personalities.

Contents

Measuring Skulls and Early Human History

In the 1700s, scientists started looking closely at skulls. Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton wrote about the hole at the base of the skull in humans and animals. Later, Pieter Camper invented the "facial angle." This was a way to measure the angle of the face from the nose to the ear, and from the jaw to the forehead. Camper used this to compare human skulls with animal skulls. He claimed that ancient statues had a 90° angle, Europeans 80°, and some African people 70°.

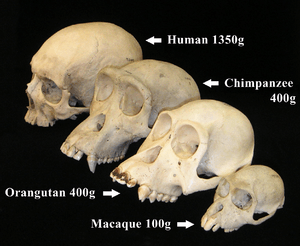

Anders Retzius in Sweden came up with the "cephalic index." This measured the shape of the head (long and thin, short and broad, or in-between). This helped scientists classify ancient human remains found in Europe. Researchers like Paul Broca continued this work. Today, scientists still use skull measurements to identify different early human species from fossils. For example, Homo erectus and Homo sapiens bodies look similar, but their skulls are very different.

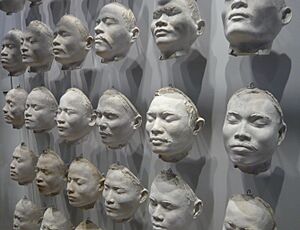

Samuel George Morton collected hundreds of human skulls in the 1800s. He wrote books like Crania Americana (1839). Morton believed he could tell how smart people were by the size of their skulls. He thought a bigger skull meant a bigger brain and more intelligence. Modern science shows a small link between brain size and intelligence, but it's not as simple as Morton thought.

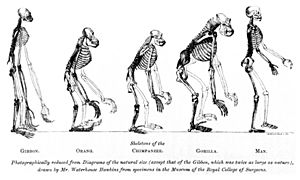

In 1856, a Neanderthal skull was found. This discovery helped start the study of paleoanthropology (the study of ancient humans). T. H. Huxley compared ape and human skeletons. His work supported Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, which Darwin wrote about in On the Origin of Species (1859). Huxley also suggested that humans and apes came from a common ancestor.

Eugène Dubois found "Java Man" in Indonesia in 1891. This was an early Homo erectus fossil. It showed that humans had a very long history outside of Europe.

Body Types and Personality

For a long time, people tried to link body measurements to personality or intelligence. Franz Joseph Gall developed "cranioscopy" in the early 1800s. This was the idea that the shape of a person's skull could show their personality and mental abilities. His student, Johann Spurzheim, later called this "phrenology." These ideas were very popular in the 1800s and early 1900s.

In the 1940s, William Sheldon used anthropometry to create "somatotypes." He believed that a person's body type could tell you about their personality. He divided body types into "endomorphic" (round), "ectomorphic" (thin), and "mesomorphic" (muscular). Today, people who do weight training sometimes use these terms.

Using Measurements for Identification

Bertillon and Early Criminology

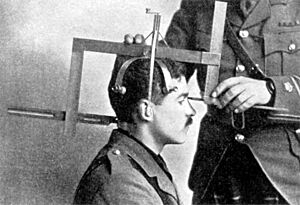

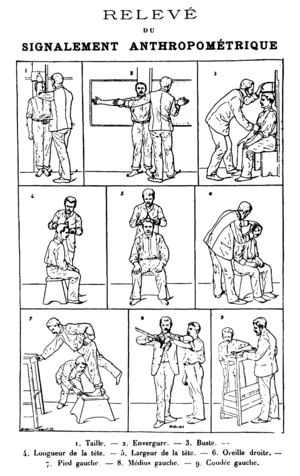

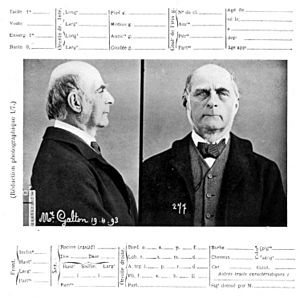

In 1883, a Frenchman named Alphonse Bertillon created a system to identify people. It was called "Bertillonage." He found that certain body measurements, especially of bones, stayed the same throughout adult life. Bertillon thought that if these measurements were taken carefully, every person could be identified. His main goal was to identify "repeat offenders" (people who committed crimes again). Before this, police only had general descriptions or photos, which were hard to organize.

The system used 10 measurements, including height, arm span, head length, and foot length. These details, along with a photo, were put on cards. This made it possible to find someone even if they gave a false name.

Bertillonage became popular in police forces in many countries. However, it had problems. The tools were expensive, and it was easy to make mistakes. Also, Francis Galton showed that many of the measurements were linked (like arm length and leg length are both related to height). Eventually, the system was replaced by fingerprints, which were simpler and more reliable. Later, genetics also became a powerful tool for identification.

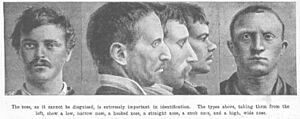

Physiognomy

Physiognomy was the idea that a person's physical features, especially their face, could show their character traits. Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909) was a famous supporter of this idea. He tried to find links between a person's body measurements and whether they might commit crimes. He believed that certain skull and facial features could show if someone was a "born criminal." He used tools like craniometers to measure these features.

Human Groups and Origins

Phylogeography is the study of how human groups moved around the world, especially in ancient times. In the past, anthropologists used anthropometry to try and classify different "races" of humans. Some even tried to say that certain groups were better than others. For example, Arthur de Gobineau divided people into three main groups based on climate and location.

Scientists like François Bernier and Carl Linnaeus also tried to classify people based on things like hair, nose shape, and skin color. As they learned to measure skulls, they started using skull shape for classification.

Ideas of "scientific racism" became popular. Georges Vacher de Lapouge divided humanity into different "races" based on head shape, like "long-headed" (Aryan) and "short-headed." His ideas influenced Nazi thinking in Germany. However, during the 1920s and 1930s, scientists like Franz Boas began to show that these ideas were wrong. Boas used the cephalic index to prove that the environment could change head shape, not just "race." This helped to show that the idea of fixed biological races was incorrect.

Race and Brain Size (Historical Views)

Historically, some studies tried to link "race" to brain size. For example, Samuel George Morton claimed in 1839 that Caucasians had the biggest brains, followed by Native Americans, and then African people. Paul Broca also made similar claims in 1873 by weighing brains.

However, many of these studies have been criticized. Scientists like Stephen Jay Gould argued that Morton's data was biased. Later studies re-examined Morton's work and found that while there were some errors, they were mostly random, not intentional to support his ideas.

Important scientists like Rudolf Virchow in Germany rejected the idea of using skull measurements to classify "races." He said that people in Europe were a "mixture of various races." He also stated that skull measurements showed that no one European "race" was superior. Virchow eventually said that measuring skulls was not a good way to classify people.

Modern science has shown that differences in brain size do not necessarily mean differences in intelligence. For example, women tend to have smaller brains than men, but they have more complex connections in certain brain areas. The idea of biologically distinct races has been proven wrong by modern genetics.

See also

- Anthropometry

- Anthropometric history

- Historical race concepts

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |