Thomas Henry Huxley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Henry Huxley

|

|

|---|---|

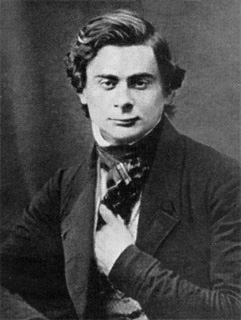

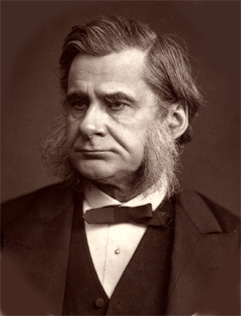

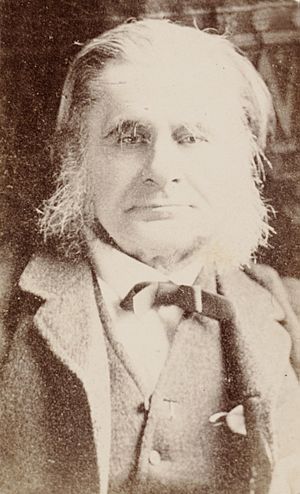

Woodburytype print of Huxley (1880 or earlier)

|

|

| Born | 4 May 1825 |

| Died | 29 June 1895 (aged 70) Eastbourne, Sussex, England

|

| Education |

|

| Known for | Evolution, science education, agnosticism |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Zoology; comparative anatomy |

| Institutions | Royal Navy, Royal College of Surgeons, Royal School of Mines, Royal Institution University of London |

| Academic advisors | Thomas Wharton Jones |

| Notable students | |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | |

| Signature | |

|

|

Thomas Henry Huxley (born May 4, 1825 – died June 29, 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist. He was an expert in comparative anatomy, which is the study of how different animals' bodies are built. He is famous for strongly supporting Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. People called him "Darwin's Bulldog" because he was so determined.

Huxley played a big part in making science education better in Britain. He also spoke out against extreme religious views that disagreed with science. In 1869, he created the word "agnosticism". This term describes the idea that we can't know for sure if God exists.

Huxley didn't go to school much. He mostly taught himself. He became one of the best comparative anatomists of his time. He studied invertebrates (animals without backbones) and later vertebrates (animals with backbones). He especially looked at how apes and humans are related. After studying Archaeopteryx (an ancient bird) and Compsognathus (a small dinosaur), he believed that birds came from small meat-eating dinosaurs. Many scientists still believe this today.

Huxley's work on animal anatomy was excellent. But he is most remembered for his strong support of evolution. He also did a lot of public work to promote science education. These efforts greatly changed society in Britain and other places.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Thomas Henry Huxley was born in Ealing, England, which was a village back then. He was one of eight children. His family was not rich. His father was a math teacher, but his school closed. This made things hard for the family. Thomas left school when he was only 10 years old. He had only two years of formal schooling.

Despite this, Huxley was determined to learn. He taught himself many things. He read books on geology and logic. As a teenager, he learned German and became fluent. He even helped Charles Darwin translate German scientific papers. He also learned Latin and enough Greek to read old texts.

As a young adult, he became an expert on invertebrates and vertebrates. He drew many pictures for his science books. He also learned a lot about religion. This helped him in his debates with religious leaders.

Huxley worked for different doctors for short times. When he was 16, he went to Sydenham College. This was an anatomy school. He kept reading and learning on his own. This made up for his lack of formal schooling.

A year later, Huxley did very well in a competition. He won a silver medal. This helped him get into Charing Cross Hospital. There, he studied with Thomas Wharton Jones. In 1845, Huxley published his first science paper. He found a new layer in hair, which is now called Huxley's layer.

When he was 20, he passed an important exam at the University of London. He won a gold medal for anatomy and physiology. But he didn't take the final exams. So, he didn't get a university degree. Still, his skills helped him join the Royal Navy.

Voyage of the Rattlesnake

When he was 20, Huxley was too young to become a licensed doctor. He also had debts. So, he joined the Royal Navy. He became an Assistant Surgeon on HMS Rattlesnake. This ship was going on a journey to explore New Guinea and Australia.

The Rattlesnake left England in December 1846. In the southern hemisphere, Huxley spent his time studying marine invertebrates. He sent his discoveries back to England. His paper "On the anatomy and the affinities of the family of Medusae" was published in 1849. In this paper, Huxley grouped together different sea creatures like jellyfish. He showed they all had two cell layers around a central stomach. This is a key feature of the group now called Cnidaria.

When Huxley returned to England in 1850, his work was recognized. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. The next year, at 26, he received the Royal Society Medal. He also met Joseph Dalton Hooker and John Tyndall. They became his lifelong friends. The Navy kept him on staff. This allowed him to study the specimens he collected during the voyage.

Later Life and Work

In 1854, Huxley left the Navy. He became a professor of natural history at the Royal School of Mines. He also worked for the British Geological Survey. He held many other important positions. He was a professor at the Royal Institution and the Royal College of Surgeons. He was also president of the British Science Association and the Royal Society.

The 31 years Huxley spent at the Royal School of Mines were very busy. He worked on vertebrate fossils. He also worked on many projects to improve science in Britain. Huxley retired in 1885 due to health issues. He received a pension of £1200 a year.

Huxley's home in London was at 4 Marlborough Place. He wrote many of his works there. The house was made bigger in the 1870s. He held informal Sunday gatherings there.

In 1890, he moved to Eastbourne. He bought land and built a house called 'Hodeslea'. There, he edited his nine volumes of Collected Essays. He died in 1895 in Eastbourne from a heart attack. He was buried in London at East Finchley Cemetery. His wife and eldest son, Noel, are also buried there.

Family Life

Huxley and his wife, Henrietta Anne Heathorn, had five daughters and three sons:

- Noel Huxley (1856–1860), who died young.

- Jessie Oriana Huxley (1856–1927).

- Marian Huxley (1859–1887), an artist.

- Leonard Huxley (1860–1933), a writer. His sons became famous scientists and authors.

- Rachel Huxley (1862–1934).

- Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley (1863–1940), a singer.

- Henry Huxley (1865–1946), a doctor.

- Ethel Huxley (1866–1941).

Huxley was a caring father. He stayed close with his children. His descendants include famous people like Sir Julian Huxley (a biologist and first Director of UNESCO), Aldous Huxley (a famous author), and Sir Andrew Huxley (who won the Nobel Prize).

Public Service and Honors

From 1870 onwards, Huxley spent less time on science research. He took on many public duties. He served on eight Royal Commissions between 1862 and 1884. These commissions investigated important issues. He was a Secretary of the Royal Society and later its President. He also led the Geological Society.

Huxley was a key person in reforming the Royal Society. He also convinced the government to support science. He helped establish science education in British schools and universities.

He received many high honors for his work. The Royal Society made him a Fellow when he was 25. He received the Royal Medal in 1852. He was the youngest biologist to get this award. Later, he received the Copley Medal and the Darwin Medal. The Geological Society gave him the Wollaston Medal. He also received the Linnean Medal.

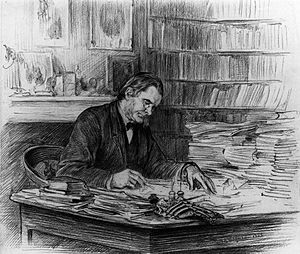

by Bassano c. 1883

In 1873, the King of Sweden made Huxley a Knight of the Order of the Polar Star. He also became a member of many foreign scientific groups. In 1892, he was appointed a Privy Councillor. This was a special recognition for his public service.

Huxley was a very strong supporter of evolution for about 30 years. Many people saw him as the top advocate for science in the 19th century.

Studying Ancient Animals

In the first part of his career, Huxley studied 'persistent types' in fossils. This meant he thought major new groups of animals didn't appear very often. He also thought that many ancient groups of plants never died out. Over time, Huxley changed his mind as he learned more about fossils.

Huxley's detailed work on anatomy was always excellent. He studied fossil fish. He wanted to show how different groups of animals were related through evolution. He discovered that lobed-finned fish (like coelacanths) have a single bone connecting their fins to their bodies. This was important for understanding how tetrapods (four-legged animals) evolved.

He also studied fossil reptiles. He showed that birds and reptiles are closely related. He grouped them together as Sauropsida. His papers on Archaeopteryx and the origin of birds were very important.

Huxley didn't do much work on fossil mammals, except for one famous case. During a trip to America, he saw amazing fossil horses. These were found by Othniel Charles Marsh at Yale University's Peabody Museum. Marsh had found a series of horse fossils. They showed how horses changed over millions of years. They went from small, four-toed forest animals to larger, single-toed grassland animals.

This discovery convinced Huxley that evolution happened gradually. It also showed that modern horses likely came from North America. Huxley then included the story of horse evolution in his lectures. Marsh said that Huxley "gave up his own opinions in the face of new truth."

Supporting Darwin's Ideas

Huxley was not always convinced by the idea of evolution. He had criticized earlier theories of change in species. But then he learned about Darwin's ideas. Darwin shared his work with a small group of friends, including Huxley, before publishing it.

In 1858, Alfred Russel Wallace sent Darwin his paper on natural selection. This paper, along with some of Darwin's notes, was presented to the Linnean Society. Huxley's famous reaction was: "How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!" He wasn't fully sure if natural selection was the main way evolution happened. But he thought it was a good idea to work with.

The most important question was whether evolution happened at all. Darwin's book, On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, convinced Huxley completely. Huxley admired how Darwin collected and used evidence. This formed the basis of his strong support for Darwin.

Huxley's support began with a positive review of the Origin in the Times newspaper in December 1859. He also wrote articles and gave lectures. Meanwhile, Richard Owen wrote a very negative review of the Origin. Owen also helped Samuel Wilberforce write another critical review. So, Huxley and Wilberforce became the main public debaters for their sides.

After his death, Huxley became known as "Darwin's Bulldog." This nickname refers to his bravery and strong arguments in debates. It also suggests he protected Darwin. Huxley himself may have created this nickname.

The Oxford Debate

Huxley famously debated Samuel Wilberforce, the Bishop of Oxford. This happened on June 30, 1860, at the British Association meeting in Oxford. Huxley had planned to leave Oxford. But he met Robert Chambers, who wrote a book about evolution. Chambers asked for his help, so Huxley stayed for the debate.

The debate followed a paper by John William Draper. John Stevens Henslow, Darwin's old tutor, was the chairman. Wilberforce opposed Darwin's theory. Huxley, Joseph Dalton Hooker, and Lubbock supported it. Even Robert FitzRoy, who was captain of HMS Beagle with Darwin, spoke against Darwin.

Wilberforce had criticized evolution before. For this debate, Richard Owen coached him. Wilberforce repeated arguments from his review. Then he made a famous joke at Huxley. He asked if Huxley was descended from an ape on his mother's side or his father's side. Huxley's reply was powerful. He said he would rather be descended from an ape than a man who misused his talents to stop debate. The exact words are not known, but the story was widely told.

Most people thought Huxley won the debate. This debate greatly increased Huxley's fame. It also showed him how important public debate was. It made it clear that Darwin's ideas could not be easily ignored. Instead, they would be strongly defended. The debate also helped promote science as a profession. It showed the need for more science education.

Man's Place in Nature

For almost ten years, Huxley focused on the relationship between humans and apes. This led to a big clash with Richard Owen. Owen was a brilliant anatomist but not well-liked. Huxley's work showed that Owen's ideas about the human brain were wrong. Owen claimed that humans had unique brain features not found in other mammals.

Huxley gave lectures to workers, students, and the public. These talks were later published. His most famous work was Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature (1863). In this book, he discussed the key issues of human evolution. This was years before Charles Darwin published his Descent of Man in 1871.

Darwin had hinted that his theory would shed light on human origins. Owen had argued that humans were so different from apes that they belonged in their own group. Darwin disagreed. Huxley proved Owen wrong. He showed that apes had the same brain structures Owen claimed were unique to humans.

This debate was widely publicized. It showed Huxley was not only a strong debater but also a better anatomist than Owen. It helped establish Huxley's leadership in comparative anatomy. It also marked the start of Owen's decline in the eyes of other biologists.

Huxley also studied ancient human fossils. In 1862, he examined the Neanderthal skull-cap. This was the first fossil of an early human species. He saw that its brain case was surprisingly large. Huxley also started to study physical anthropology. He classified human races into different categories based on physical traits.

Natural Selection and Agnosticism

Huxley was not always in full agreement with Darwin. Darwin was a field naturalist, while Huxley was an anatomist. This gave them different views of nature. Huxley was an empiricist. He trusted what he could see. He felt that natural selection couldn't be fully proven until scientists could see new species becoming infertile with each other.

Despite this, Huxley didn't believe in any other theory. He saw that if evolution happened through variation and selection, then ideas could also be selected. He said, "A theory is a species of thinking, and its right to exist is coextensive with its power of resisting extinction by its rivals." This is similar to the idea of meme theory.

Darwin argued that the evidence Huxley wanted was impossible to get. He felt that his theory explained many problems. Huxley's doubts about natural selection spread among other scientists. This was because comparative anatomy could explain how species were related, but not the exact way they changed.

Huxley was a pallbearer at Charles Darwin's funeral on April 26, 1882.

The X Club

In November 1864, Huxley started a dining club called the X Club. Its goal was to promote science. The club had nine members, mostly Huxley's close friends. They included John Tyndall, J. D. Hooker, and John Lubbock. All but one were Fellows of the Royal Society.

They met before Royal Society Council meetings. Their first goal was to get the Copley Medal for Darwin, which they succeeded in doing.

The X Club also wanted a journal to share their ideas. They bought Reader, a weekly paper. Huxley was already part-owner of the Natural History Review. They changed these journals to support Darwin's ideas. Both journals eventually failed. But they helped spread evolutionary ideas at a key time.

The X Club then helped start Nature magazine in 1869. This time, they made sure it had a permanent editor, Norman Lockyer. Nature became a very important science journal.

The X Club was most powerful from 1873 to 1885. During this time, Hooker, Spottiswoode, and Huxley were all Presidents of the Royal Society one after another. The club continued to meet until the last member, Lord Avebury, died.

Huxley was also a member of the Metaphysical Society. This group included clergy and people with many different opinions.

Impact on Education

When Huxley was young, there were few science degrees in British universities. Most biologists learned through medical training or by teaching themselves. By the time he retired, biological sciences were well-established in universities. Huxley was the most important person in this change.

Teaching Science

In the early 1870s, the Royal School of Mines moved to new buildings. This allowed Huxley to focus more on laboratory work in biology. This idea came from German universities. Students learned by dissecting animals and using microscopes.

Huxley's assistants were carefully chosen. They all became leaders in biology in Britain. They spread Huxley's ideas. Some famous students included Michael Foster, Ray Lankester, and William Flower. It's amazing how many great scientists came from Huxley's teaching.

Huxley's teaching focused a lot on morphology (the study of forms and structures). This method was used in biology education for 100 years. It changed when cell biology and molecular biology became more important. It's interesting that Huxley's teaching didn't include much about field naturalists like Darwin. These naturalists had collected much of the evidence for evolution.

Huxley was best at comparative anatomy. He chose to teach what he knew best. This made biology teaching very focused on one area for a long time.

Schools and the Bible

Huxley also greatly influenced British schools. In 1870, he was elected to the London School Board. For primary schools, he supported teaching many subjects. These included reading, writing, math, art, science, and music. For secondary education, he suggested two years of general studies. Then, students would focus on a specific area. His famous 1868 lecture, On a Piece of Chalk, showed how science could explain the history of Britain from a simple piece of chalk.

Huxley believed the Bible should be read in schools. This might seem strange for an agnostic. But he thought the Bible had important moral lessons and beautiful language. However, he wanted an edited version of the Bible. He wanted to remove parts that disagreed with science. He believed children should not be taught things that teachers didn't believe. The Board voted against his edited Bible idea. But they also voted against using public money for church schools. Huxley said he would never support the state forcing children into religious schools.

Huxley's work helped make British society more secular over time. Some Christians see him as the father of antitheism. But he always said he was an agnostic, not an atheist. He was a strong opponent of almost all organised religion. He especially disliked the "Roman Church". He believed it harmed morality, intellectual freedom, and political freedom. He called Auguste Comte's positivism "Catholicism minus Christianity."

Huxley created the term "agnosticism" in 1869. He explained it in 1889. It describes claims in terms of what can be known and what cannot. This term is still used today.

Adult Education

Huxley also cared about adult education. He himself was mostly self-taught. He gave lectures for working men. Many of these lectures were published. He also wrote for newspapers and magazines. He wanted to reach the general public.

In 1868, Huxley became Principal of the South London Working Men's College. Lectures by Huxley cost only a penny. The college also had a free library. Huxley believed the men who attended were as good as anyone.

Publishing his popular lectures in magazines was very effective. For example, his lecture "The Physical Basis of Life" caused a sensation. He argued that life's actions come from the chemicals in protoplasm. This idea shocked people at the time. The magazine issue was reprinted seven times.

Huxley and Human Values

Later in his life, Huxley wrote about many topics related to human values. One famous topic was Evolution and Ethics. This discussed whether biology has anything to say about moral philosophy.

Huxley believed that human mental traits, like emotions and intellect, are products of evolution. So, our tendency to live in groups and care for our young is inherited. However, he thought that our specific values and ethics are not inherited. They come from our culture and our own choices. He said, "Of moral purpose I see not a trace in nature. That is an article of exclusively human manufacture." This means we are responsible for making ethical choices.

Huxley also analyzed Jean-Jacques Rousseau's ideas about humans and society. He disagreed with Rousseau's idea that all people are born free and equal.

Huxley was known for his strong arguments and persuasive writing. He had debates with scientists, religious leaders, and politicians. He also gave many lectures and wrote articles for the public.

Royal and Other Commissions

Huxley worked on ten Royal and other commissions. These were important investigations by the British government. Most of them dealt with science, science education, medicine, or fisheries. They often involved difficult ethical and legal questions.

Royal Commissions

- 1862: On fishing for herrings in Scotland.

- 1863–1865: On sea fisheries in the United Kingdom.

- 1870–1875: On scientific instruction and the progress of science.

- 1876: On the practice of using live animals for scientific experiments (vivisection).

- 1876–1878: On the universities of Scotland.

- 1881–1882: On the laws related to medicine.

- 1884: On different types of fishing.

Other Commissions

- 1866: On the Royal College of Science for Ireland.

- 1868: On science and art education in Ireland.

Family Life and Legacy

In 1855, Huxley married Henrietta Anne Heathorn. She was an English woman he met in Sydney, Australia. They wrote letters until he could send for her to come to England.

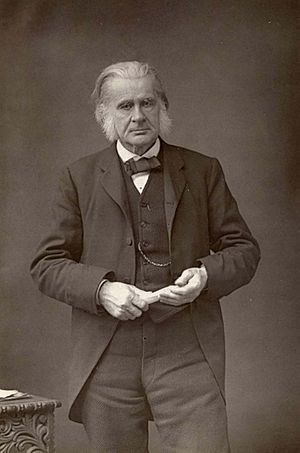

Huxley with his grandson Julian in 1893

Marian (Mady) Huxley, by her husband John Collier

|

Huxley's relationships with his family were good for his time. He was affectionate with his children. He wrote a loving letter to his eldest daughter, Jessie.

Huxley's descendants have also become very famous. His grandson Sir Julian Huxley was a leading evolutionary biologist and the first Director of UNESCO. Another grandson, Aldous Huxley, was a well-known author who wrote Brave New World. His grandson Sir Andrew Huxley won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1963. He also became President of the Royal Society, just like his grandfather.

The Huxley family has a remarkable legacy in science, literature, and public service.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Henry Huxley para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Henry Huxley para niños