John Tyndall facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Tyndall

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 2 August 1820 Leighlinbridge, County Carlow, Ireland

|

| Died | 4 December 1893 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Alma mater | University of Marburg |

| Known for | Atmosphere, physics education, Tyndall effect, diamagnetism, infrared radiation, Tyndallization |

| Awards | Royal Medal (1853) Rumford Medal (1864) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics, chemistry |

| Institutions | Royal Institution of Great Britain |

| Doctoral students | Mihajlo Idvorski Pupin |

| Signature | |

|

|

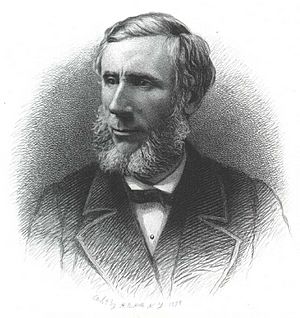

John Tyndall (born August 2, 1820 – died December 4, 1893) was an important Irish scientist. He was a physicist who lived in the 1800s. He became famous in the 1850s for studying diamagnetism. This is how some materials react to magnets.

Later, he made big discoveries about infrared radiation. This is a type of heat energy you can't see. He also studied the air around us. In 1859, he showed how carbon dioxide in the air helps warm the Earth. This is now called the greenhouse effect.

Tyndall also wrote many science books. These books helped many people learn about experimental physics. From 1853 to 1887, he was a physics professor. He taught at the Royal Institution of Great Britain in London.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

John Tyndall was born in Leighlinbridge, County Carlow, Ireland. His father was a police officer. John went to local schools in County Carlow. He learned about technical drawing and math. He also learned how to survey land.

In 1839, he started working as a draftsman. He worked for the Ordnance Survey of Ireland. Later, in 1842, he moved to Great Britain. He helped plan new railway lines. This was a busy time for building railways. Tyndall's skills were very useful.

In 1847, Tyndall decided to become a teacher. He taught math and surveying at Queenwood College. This was a boarding school in England. He wanted to keep learning new things. At Queenwood, he met Edward Frankland, another young teacher. They became good friends.

Frankland and Tyndall decided to study more science in Germany. German universities were known for their science labs. In 1848, they went to the University of Marburg. Tyndall studied there for two years. He learned a lot from his teachers, especially Professor Hermann Knoblauch. When Tyndall returned to England in 1851, he had a great science education.

First Science Work

Tyndall's first important work was on magnetism. He studied how different materials react to magnets. This was from 1850 to 1856. He wrote important reports with Knoblauch. One report was about how crystals react to magnets.

His work quickly made him known to other scientists. In 1852, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society. This is a very respected science group. In 1853, he became a Professor of Physics. He worked at the Royal Institution in London. This was a big honor. Michael Faraday, a famous scientist, admired Tyndall's work. Later, Tyndall took over Faraday's positions when Faraday retired.

Mountain Climbing and Glaciers

Tyndall first visited the Alps mountains in 1856. He went there for science, but he also became a skilled mountain climber. He visited the Alps almost every summer. He was part of the first team to climb the Weisshorn in 1861. He also led a team to climb the Matterhorn in 1868. He was part of the "Golden age of alpinism". This was when many difficult Alpine peaks were climbed for the first time.

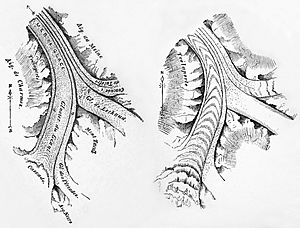

In the Alps, Tyndall studied glaciers. He was very interested in how glaciers move. His ideas about glacier flow caused some debate. He disagreed with another scientist, James David Forbes. Tyndall's explanation used the idea of regelation. This is when ice melts under pressure and then refreezes. Forbes did not agree with this idea.

Many places are named after John Tyndall. These include Tyndall Glacier in Chile. There are also Tyndall Glacier in Colorado and Tyndall Glacier in Alaska. Mountains like Mount Tyndall in California and Mount Tyndall in Tasmania are also named for him.

Major Science Discoveries

Studying glaciers made Tyndall think about how sunlight heats the Earth. He knew that heat from the sun enters the atmosphere easily. But heat from the warmed Earth, called "obscure heat" or infrared radiation, doesn't escape as easily. This is what we now call the greenhouse effect.

In 1859, Tyndall began to study how different gases absorb heat. He used special tools to measure how much heat gases absorbed. On May 18, 1859, he wrote in his journal, "Experimented all day; the subject is completely in my hands!" He showed that gases like coal gas and ether strongly absorbed infrared heat.

On June 10, he gave a lecture about his findings. He explained that the atmosphere lets sunlight in. But it traps the heat that radiates from the Earth. This causes the Earth's surface to warm up.

Tyndall's research on heat and air led to many important discoveries:

- He explained how the Earth's atmosphere gets warm. Different gases in the air absorb infrared radiation. He was the first to correctly measure how much infrared heat gases like nitrogen, oxygen, water vapour, carbon dioxide, ozone, and methane absorb. He found that water vapour is the most important gas for controlling air temperature. It absorbs the most heat. Before Tyndall, people thought the atmosphere warmed the Earth. But he was the first to prove it. He showed that water vapor strongly absorbed infrared radiation.

- He showed how heat is absorbed and released at the tiny molecule level. He was likely the first to show that heat from chemical reactions comes from new molecules forming. He also showed how invisible infrared light could become visible light. He called this calorescence.

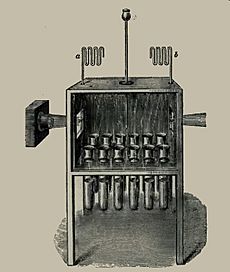

- He studied how light scatters when it hits tiny particles in the air. This is now called the Tyndall Effect or Tyndall Scattering. He used strong lights to see these particles. He invented tools like the nephelometer. These tools help us see tiny particles in the air and liquids.

- He was the first to see and report thermophoresis in aerosols. This is when tiny particles move away from hot objects.

- He showed that liquids and their vapors absorb heat in similar ways.

- He proved that infrared heat behaves like visible light. It can be reflected, bent, and split.

- He invented a way to measure carbon dioxide in human breath. This system is still used in hospitals today. It helps monitor patients during surgery.

- He helped confirm that ozone is a form of oxygen.

- He found a simple way to get "optically pure" air. This is air with no visible dust or particles. He used a box coated with sticky glycerin. Dust would stick to the walls. He then put boiled meat broths in this pure air and in regular air. The broths in pure air stayed fresh for months. The ones in regular air spoiled quickly. This showed that tiny living things, or "germs," cause food to spoil. This supported Louis Pasteur's ideas.

- Later, Tyndall found that some bacteria have tough bacterial spores. These spores can survive boiling. He found a way to kill these spores. This method is called "Tyndallization". It was the first way to destroy bacterial spores. This helped prove the "germ theory" of disease.

- He invented a better respirator for firefighters. This hood filtered smoke and bad gases from the air.

- He studied how sound travels through air. He helped develop better foghorns. He showed that sound bounces back when it hits air masses of different temperatures. This is why sounds can be heard differently on different days.

Tyndall wrote over 147 science papers. Most of them were between 1850 and 1884. That's more than four papers every year!

In his lectures, Tyndall loved to show exciting experiments. He showed how light could travel down a stream of water. This was called the "light fountain." It showed the basic idea behind modern fibre optic technology.

Understanding Molecules

Tyndall was a great experimenter. He built his own lab tools. He wanted to understand how tiny molecules work. He believed that all physical things, like heat, magnetism, and sound, come from how molecules behave.

He thought that different molecules absorb heat differently. This is because their structures make them vibrate in different ways. He saw that molecules absorb different amounts of heat at different frequencies. He also saw that molecules behave differently from the atoms they are made of. For example, nitric oxide (NO) absorbed much more heat than nitrogen (N2) or oxygen (O2).

Tyndall also showed that molecules that absorb heat well also release heat well. This idea was consistent with how resonators work. He believed that light could break down molecules. This meant that the whole molecule couldn't be the only thing vibrating. There had to be smaller parts inside.

A Great Teacher

John Tyndall was not just a scientist. He was also a passionate teacher. He wanted everyone to understand science. He gave hundreds of public lectures in London. When he toured the United States in 1872, many people paid to hear him speak about light.

People said that Tyndall was great at making science interesting. When he lectured, the hall was always full. He believed teaching was a "higher, nobler, and more blessed calling."

His books were very popular. Most of them were for regular people, not just experts. He wrote more than a dozen science books. Many were translated into other languages. He was one of the most famous physicists of his time. This was because he was such a good teacher.

In his book The Forms of Water (1872), he wrote to his young readers: "It has been a true pleasure to me to have you at my side so long... I should like to teach you all things; showing you the way to profitable exertion, but leaving the exertion to you." He wanted his readers to think for themselves.

His book Sound (1867) started by saying he wanted to make acoustics interesting for everyone. Even those without much science background. His most famous book was Heat: a Mode of Motion (1863). It was in print for over 50 years. It was known for its clear explanations and great experiments.

Tyndall's main books, Heat, Sound, and Light, showed the latest ideas in experimental physics. He was the first to explain many of these new ideas to a wide audience. His books focused on lab science and did not use complex math.

Science and Beliefs

Many scientists in Tyndall's time believed that science and religion worked together. But Tyndall was part of a group called the X Club. This group strongly supported Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. They believed science and religion should be kept separate. Thomas Henry Huxley, a famous anatomist, was a close friend of Tyndall and a key member of this group.

In 1874, Tyndall was the president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. He gave a speech in Belfast. He talked about the history of evolution. He said that religious feelings should not "intrude on the region of knowledge." This speech caused a big stir. Newspapers all over the world reported on it. It helped make the idea of evolution more accepted.

Tyndall believed that human reason was important for knowledge. He thought that science should be free to explore without religious limits. He also wrote essays where he questioned the power of prayers. Many people thought Tyndall was an agnostic. This means he believed we can't know if God exists. He once said, "The real mystery of the universe lies unsolved, and... is incapable of solution."

Personal Life

Tyndall married later in life, at age 55. His wife was Louisa Hamilton. She was 30 years old. They built a summer home in the Swiss Alps in 1877. Tyndall had lived at the Royal Institution for many years. After marrying, he moved to a house near Haslemere. They had a happy marriage but no children. He retired from the Royal Institution at 66 due to health problems.

Tyndall became quite wealthy from his popular books and lectures. He gave a lot of his money to charity. After his lecture tour in the United States in 1872, he donated all his earnings to support science in America.

Death

John Tyndall died in 1893 at age 73. He passed away from an accident at his home in Haslemere. He was buried there.

After his death, his wife Louisa kept his papers. She planned to write his official biography. But she took a long time. The book was finally published in 1945, after she had passed away.

John Tyndall is remembered with a memorial in the Swiss Alps. It is near his holiday home and the Aletsch Glacier, which he studied.

John Tyndall's Books

- Tyndall, J. (1860), The Glaciers of the Alps

- Tyndall, J. (1862), Mountaineering in 1861. A Vacation Tour

- Tyndall, J. (1865), On Radiation: One Lecture

- Tyndall, J. (1868), Heat : A Mode of Motion

- Tyndall, J. (1869), Natural Philosophy in Easy Lessons (a physics book for schools)

- Tyndall, J. (1870), Faraday as a Discoverer

- Tyndall, J. (1870), Researches on Diamagnetism and Magne-Crystallic Action

- Tyndall, J. (1871), Hours of Exercise in the Alps

- Tyndall, J. (1871), Fragments of Science: A Series of Detached Essays, Lectures, and Reviews

- Tyndall, J. (1872), Contributions to Molecular Physics in the Domain of Radiant Heat

- Tyndall, J. (1873), The Forms of Water in Clouds & Rivers, Ice & Glaciers

- Tyndall, J. (1873), Six Lectures on Light

- Tyndall, J. (1876), Lessons in Electricity at the Royal Institution (for students)

- Tyndall, J. (1878), Sound; Delivered in Eight Lectures

- Tyndall, J. (1882), Essays on the Floating Matter of the Air, in Relation to Putrefaction and Infection

- Tyndall, J. (1887), Light and Electricity: Notes of Two Courses of Lectures

- Tyndall, J. (1892), New Fragments (various essays for a wide audience)

See also

In Spanish: John Tyndall para niños

In Spanish: John Tyndall para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |