Edward Frankland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Frankland

|

|

|---|---|

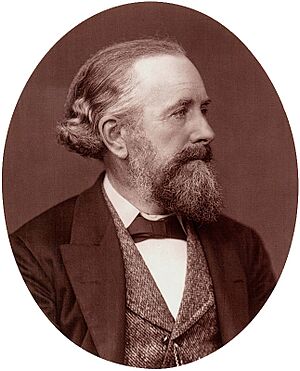

Edward Frankland in his 20s

|

|

| Born | 18 January 1825 Catterall, Lancashire, England

|

| Died | 9 August 1899 (aged 74) Gålå, Gudbrandsdal, Norway

|

| Occupation | Research chemist |

| Known for | Pioneer in water analysis Discoverer of the principle of valency in chemistry Organometallic chemistry Organotin chemistry |

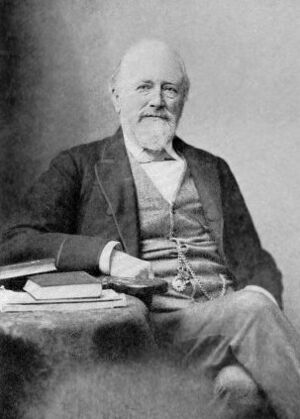

Sir Edward Frankland (born January 18, 1825 – died August 9, 1899) was an English chemist. He was a very important scientist who helped start a field called organometallic chemistry. He also came up with the idea of valency, which explains how atoms combine. Edward Frankland was an expert in checking water quality. He worked for many years to study and improve London's water. He also researched how flames glow and how air pressure affects gases. He was even one of the scientists who discovered helium.

Contents

Edward Frankland's Early Life

Edward Frankland was born in Catterall, a village in Lancashire, England. He was baptized in Churchtown, Lancashire, on February 20, 1825. His mother, Margaret Frankland, later married William Helm, who was a cabinet-maker in Lancaster.

From ages 3 to 8, Edward lived and went to school in different towns. These included Manchester, Churchtown, Salford, and Claughton. In 1833, his family moved to Lancaster. There, he attended a private school run by James Wallasey. This is where he first became interested in chemistry. He especially enjoyed reading books by Joseph Priestley from the Mechanics Institute Library.

At age 12, Edward went to the Lancaster Free Grammar School. This school had also educated other famous scientists like William Whewell. Edward's interest in chemistry grew even more because of a court case he heard about. It was held at Lancaster Castle, which was next to his school. The case was about a company polluting the air with a gas called muriatic acid. Edward was allowed to skip school to attend the trial, which fascinated him.

Edward wanted to become a doctor, but the training was too expensive for him. So, he decided to become an apprentice at a pharmacy.

Becoming a Chemist

In 1840, Edward became an apprentice to Stephen Ross, a pharmacist in Lancaster. His job involved mixing large amounts of chemicals to make medicines. He used tools like a mortar and pestle.

During his six-year apprenticeship, Frankland also went to the Lancaster Mechanics' Institute. He took classes in a small laboratory set up by a local doctor, James Johnson. Other young men interested in science, like Robert Galloway and William Turner, were also part of this group.

With Dr. Johnson's help, Frankland got a place in the Westminster laboratory of Lyon Playfair in 1845. While there, he took Playfair's chemistry lectures. He passed the final exam, which was the only written exam he ever took.

In 1847, Frankland visited Germany and met other chemists, including Robert Bunsen. He then worked as a science teacher at a school in Hampshire. But the next year, he went back to Germany to study full-time at the University of Marburg. Robert Bunsen was a very influential teacher there, which was a big reason Frankland chose Marburg. A year later, Frankland moved to Justus von Liebig's laboratory at Giessen. By this time, Frankland was already doing his own research and had published some of his findings.

Teaching and Recognition

In 1850, Frankland returned to England to become a professor at Putney College for Civil Engineers in London. A year later, he became a chemistry professor at a new school, now known as the University of Manchester. He also taught chemistry at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London starting in 1857. In 1863, he became a chemistry professor at the Royal Institution in London. For twenty years, Frankland also taught at the Royal School of Mines in London.

Edward Frankland was recognized for his important work. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1853. This is a very high honor for scientists. He received the Royal Medal in 1857 and the Copley Medal in 1894 from the Royal Society. He was also made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1897, which means he was given the title "Sir."

Edward Frankland married Sophie Fick in 1851. After she passed away in 1874, he married Ellen Frances Grenside in 1875. He died while on holiday in Norway. His body was brought back to Britain and buried near his home in Reigate, Surrey. His son, Percy Frankland, also became a famous chemist.

Edward Frankland's Scientific Discoveries

From a young age, Frankland was very successful in his scientific research. He first focused on solving problems like isolating certain organic compounds. But he soon started creating new chemical substances.

Organometallic Chemistry and Valency

Frankland discovered a new type of chemical compound called organometallic compounds. He made substances like diethylzinc and dimethylzinc. He did this by reacting ethyl iodide and methyl iodide with metallic zinc.

What Frankland learned from these new compounds was even more important. He realized that atoms of each element have a specific "combining power." This means they can only join with a certain number of other atoms. He published this idea in 1852. This concept is now known as the theory of valency. This theory has been central to how we understand chemistry ever since. It forms the basis of modern structural chemistry. In 2015, Frankland's 1852 discovery of valency was honored with a Chemical Breakthrough Award.

Water Quality and Analysis

Frankland's most important work in applied chemistry was related to water supply. In 1868, he became a member of a special commission. This group studied the pollution of rivers. The government gave him a fully equipped laboratory. For six years, he carried out research on how sewage and factory waste polluted rivers. He also studied how to purify water for people to drink.

In 1865, Frankland started making monthly reports on the quality of water supplied to London. He continued these reports for the rest of his life. At first, he was very critical of the water quality. But in later years, he became convinced that London's water was generally good and safe.

Frankland used both chemical and bacteriological methods for his water analysis. He was not happy with the methods used at the time. So, he spent two years developing new and more accurate ways to test water.

Flames, Pressure, and Helium

In 1859, Frankland spent a night on top of Mont Blanc, a very high mountain. He was with another scientist, John Tyndall. One goal of their trip was to see if a candle burned differently at high altitudes. They found that it did not.

However, Frankland noticed that the candle gave off very little light at the summit. This led him to study how air pressure affects how brightly flames burn. He found that higher pressure makes flames glow more. For example, hydrogen gas usually burns without much light. But under high pressure, it burns with a bright, glowing flame. This showed him that solid particles are not the only thing that makes a flame bright.

He also showed that the light from a hot, dense gas looks like the light from a hot liquid or solid. He observed that as gas pressure increased, the sharp lines in its light spectrum would broaden. They would eventually merge into a continuous spectrum, like a liquid.

Frankland applied these findings to study the sun. Working with Sir Norman Lockyer, he suggested that the outer layers of the sun are made of gases or vapors, not liquids or solids.

Frankland and Lockyer also helped discover helium. In 1868, they saw a bright yellow line in the sun's light spectrum. This line did not match any known substance on Earth. They believed it belonged to a new, unknown element, which they called helium. This was the first time an element was discovered in space before it was found on Earth!

Awards and Honours

- Fellow of the Royal Society, 1853

- Royal Medal, 1857, for his research on organic compounds.

- Copley Medal, 1894

- Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, 1897

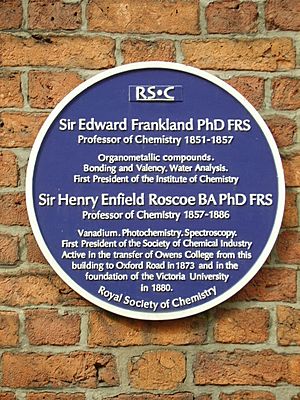

- Blue plaque, from the Royal Society of Chemistry, at Quay Street, Manchester.

- National Chemical Landmark Blue plaque from the Royal Society of Chemistry, at Lancaster Royal Grammar School, 2015.

- Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award from the American Chemical Society, for his 1852 discovery of the theory of valency, awarded to the University of Manchester, 2015.

- Blue plaque from English Heritage, at 14 Lancaster Gate, Bayswater, London in June 2019.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Edward Frankland para niños

In Spanish: Edward Frankland para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |