Evolution of fish facts for kids

The evolution of fish started around 530 million years ago during a time called the Cambrian explosion. This was when early chordates (animals with a rod-like support structure) developed a skull and a backbone. This led to the first animals with skulls (craniates) and backbones (vertebrates).

The first fish were Agnatha, or jawless fish. Examples include Haikouichthys. Later in the Cambrian period, eel-like jawless fish called conodonts appeared, along with small, armored fish called ostracoderms. Most jawless fish are now extinct, but lampreys are living examples that look similar to these ancient fish.

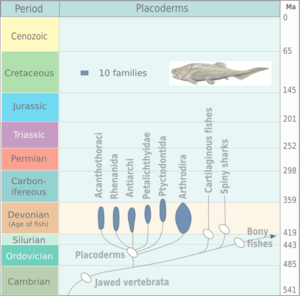

The first fish with jaws, called jawed vertebrates, likely appeared in the late Ordovician period. We find their fossils from the Silurian period. These include armored fish called placoderms (which evolved from ostracoderms) and spiny sharks. Modern jawed fish also appeared in the late Silurian: cartilaginous fish (like sharks) and bony fish. Bony fish then split into two main groups: ray-finned fish and lobe-finned fish.

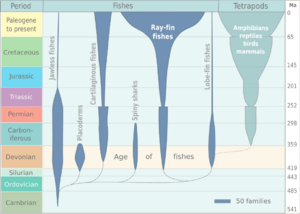

During the Devonian period, fish became incredibly diverse. This is why it's often called the age of fishes. From the lobe-finned fish, tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) evolved. Today, tetrapods include amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds. The first tetrapods appeared in the late Devonian. Having jaws was a big advantage for these early fish, allowing them to bite harder or breathe better. Fish are not a single group, because they include the ancestors of tetrapods, but not tetrapods themselves.

Fish, like many other living things, have been affected by major extinction events throughout Earth's history. The Ordovician–Silurian extinction events caused many species to disappear. The late Devonian extinction wiped out ostracoderms and placoderms. Spiny sharks vanished during the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Conodonts became extinct at the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event. More recently, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (which killed the dinosaurs) and the current Holocene extinction have also impacted fish.

Contents

Fish Families Through Time

Scientists classify living animals with backbones (vertebrates) into different groups. These groups are based on their body parts and how they work. Vertebrates are often divided into those with four limbs (tetrapods) and those without (fish).

Here are the main groups of vertebrates:

- Fish:

* Jawless fish * Cartilaginous fish (like sharks and rays) * Ray-finned fish * Lobe-finned fish

- Tetrapods (four-limbed animals):

* Amphibians * Reptiles * Birds * Mammals

There were also two groups of extinct jawed fish: the armored placoderms and the spiny sharks.

Fish might have evolved from an animal similar to a sea squirt. Sea squirt larvae look a lot like early fish. The first fish ancestors might have kept their larval form into adulthood, but this is hard to prove.

The first vertebrates, including the earliest fish, appeared about 530 million years ago during the Cambrian explosion. This was a time when many new types of living things suddenly appeared.

The first ancestors of fish were likely animals like Pikaia, Haikouichthys, and Myllokunmingia. These three groups appeared around 530 million years ago. Pikaia had a simple notochord, a rod that could have become a backbone. Unlike other animals of the Cambrian period, these groups had a basic vertebrate body plan: a notochord, simple vertebrae, and a clear head and tail. All these early vertebrates did not have jaws. They filtered tiny food particles from the seabed.

After these, clear fossil vertebrates appeared. These were heavily armored fish found in rocks from the Ordovician Period (500–430 million years ago).

The first jawed vertebrates appeared in the late Ordovician and became common in the Devonian, often called the "Age of Fishes." The two groups of bony fish, the actinopterygii and sarcopterygii, evolved and became common. The Devonian also saw most jawless fish disappear, except for lampreys and hagfish. The Placodermi, a group of armored fish, also died out. The Devonian also saw the rise of the first labyrinthodonts, which were a link between fish and amphibians.

As fish explored new places to live, their body shapes changed, and some grew much larger. The Devonian Period (395 to 345 million years ago) saw giants like the placoderm Dunkleosteus, which could grow up to seven meters long. Early air-breathing fish also appeared, some of which could stay on land for a while. These included the ancestors of amphibians.

Reptiles appeared from labyrinthodonts in the Carboniferous period. In the sea, bony fish became the main group.

Later, in the Silurian and Devonian periods, fish continued to diversify. The first animals to move onto dry land were arthropods (like insects and spiders). Some fish had lungs and strong, bony fins, allowing them to crawl onto land too.

Jawless Fish

[[File:Petromyzon marinus.003 - Aquarium Finisterrae.JPG|thumb|

}}

[[File:Evolution of jawless fish.png|thumb|How jawless fish evolved.]]

Jawless fish belong to a group called Agnatha. This name comes from Greek and means "no jaws." It includes all vertebrates without jaws. While jawless fish are a small part of today's ocean life, they were very important among early fish in the early Paleozoic Era.

Two early Cambrian animals from China, Haikouichthys and Myllokunmingia, seem to have had fins, muscles like vertebrates, and gills. They are thought to be early jawless fish. Another possible early jawless fish from the same area is Haikouella.

Many jawless fish from the Ordovician, Silurian, and Devonian periods were covered in heavy, bony, and often decorated plates. These first armored jawless fish, called Ostracoderms, are ancestors to bony fish and, eventually, to tetrapods (including humans). Ostracoderms appeared in the middle Ordovician. By the late Silurian, jawless fish were at their peak. Most ostracoderms were more closely related to jawed vertebrates than to the jawless fish that still live today, like cyclostomes (lampreys and hagfish). Jawless fish declined in the Devonian and never recovered.

Conodonts: Eel-like Swimmers

[[File:Euconodonta.gif|thumb|

}}

Conodonts looked like primitive jawless eels. They appeared 520 million years ago and died out 200 million years ago. At first, scientists only knew them from tiny, tooth-like fossils. These "teeth" might have been used for filtering food or for grasping and crushing. Conodonts ranged from one centimeter to 40 centimeters long. Their large eyes were on the sides of their heads, suggesting they weren't predators. Their muscles suggest some conodonts were good at cruising but couldn't swim in fast bursts. In 2012, scientists classified conodonts as chordates because they had fins with fin rays, V-shaped muscles, and a notochord. Some think they were similar to modern hagfish and lampreys.

Ostracoderms: Armored Fish

[[File:Astraspis desiderata.gif|thumb|

}}

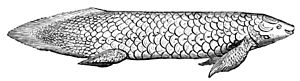

Ostracoderms (meaning "shell-skinned") were armored jawless fish from the Paleozoic Era. This term is not often used in modern classifications because it groups together different types of fish. However, it's still used informally for armored jawless fish.

Ostracoderm armor had polygonal plates that covered their heads and gills. These plates overlapped further down their bodies like scales. Their eyes were also protected. Earlier chordates used their gills for both breathing and eating. Ostracoderms used their gills only for breathing. They had up to eight separate gill pouches on the side of their heads, which were always open. Unlike invertebrates that use tiny hairs (cilia) to move food, ostracoderms used their strong throat muscles to suck in small, slow-moving prey.

The first fish fossils ever found were ostracoderms. A Swiss scientist, Louis Agassiz, received some bony armored fish fossils from Scotland in the 1830s. He had trouble classifying them because they didn't look like any living creature. He first compared them to armored fish like catfish, but later realized they had no movable jaws. In 1844, he put them into a new group called "ostracoderms."

Ostracoderms had two main groups: the more primitive heterostracans and the cephalaspids. About 420 million years ago, jawed fish evolved from one of the ostracoderm groups. After jawed fish appeared, most ostracoderm species declined. The last ostracoderms died out at the end of the Devonian period.

Jawed Fish

The vertebrate jaw likely first evolved in the Silurian period in Placoderm fish. These fish then became more diverse in the Devonian. It's thought that the first two gill arches (supports for the gills) changed to become the jaw itself and the hyoid arch (which supports the jaw). This hyoid system allows the jaw to move a lot. Recent discoveries suggest that placoderms are direct ancestors of modern bony fish.

Like most vertebrates, fish jaws are made of bone or cartilage. They open and close vertically, with an upper and a lower jaw. The jaw usually has many teeth. The skull of the last common ancestor of today's jawed vertebrates probably looked like a shark's.

Scientists believe that the first advantage of jaws wasn't for eating, but for breathing more efficiently. Jaws helped pump water over the gills of fish (like in modern fish and amphibians). Over time, the more familiar use of jaws for feeding became very important for vertebrates. Many teleost fish have changed their jaws a lot for suction feeding and jaw protrusion, leading to very complex jaws with many bones.

Jawed vertebrates evolved from earlier jawless fish.

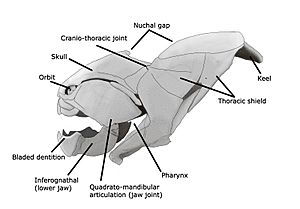

Placoderms: Armored Jawed Fish

Placoderms (meaning "plate-skinned") were extinct armored prehistoric fish. They appeared about 430 million years ago in the Early to Middle Silurian. Most of them died out during the Late Devonian Extinction event, 378 million years ago. Some survived a bit longer but completely disappeared by the end of the Devonian, 360 million years ago. They are ultimately ancestors to modern jawed vertebrates. Their heads and chests were covered with large, often decorated, armored plates. The rest of their bodies were scaled or bare, depending on the species. The armor shield was hinged, allowing placoderms to lift their heads, unlike ostracoderms. Placoderms were the first fish with jaws, which likely evolved from their first gill arches.

Spiny Sharks: Early Jawed Fish

Spiny sharks were extinct fish that shared features with both bony and cartilaginous fish. They are more closely related to and are ancestors of cartilaginous fish (like sharks). Even though they are called "spiny sharks," acanthodians appeared before true sharks. They evolved in the sea at the beginning of the Silurian Period, about 50 million years before the first sharks. Eventually, competition from bony fish was too much, and spiny sharks died out in the Permian period, about 250 million years ago. They looked like sharks, but their skin was covered with tiny, diamond-shaped plates, similar to the scales of gars.

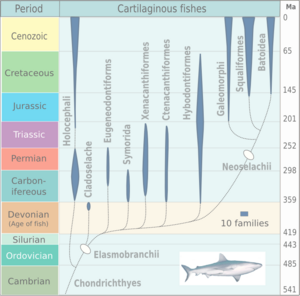

Cartilaginous Fish: Sharks, Rays, and Chimaeras

Cartilaginous fish, like sharks, rays, and chimaeras, appeared about 395 million years ago in the middle Devonian. They evolved from acanthodians. This group includes two main types: Holocephali (chimaeras) and Elasmobranchii (sharks and rays).

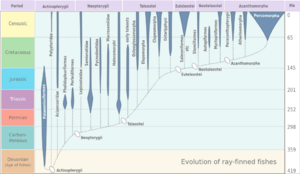

Bony Fish: The Dominant Group

Bony fish are known for having skeletons made of bone rather than cartilage. They appeared in the late Silurian, about 419 million years ago. A recent discovery suggests that bony fish (and possibly cartilaginous fish, through acanthodians) evolved from early placoderms. One group of bony fish, the ray-finned fish, has become the most common group of fish today, with about 30,000 living species.

The bony (and cartilaginous) fish groups that appeared after the Devonian got better at finding food and moving around.

Lobe-finned Fish: Ancestors of Land Animals

Scientists now believe that lungfish are the closest living fish relatives to the ancestors of four-legged land animals, not coelacanths.

Lobe-finned fish are mostly extinct bony fish. They are known for their strong, stubby fins that have a bony skeleton inside. Their fins are fleshy and connected to the body by a single bone. These fins are similar to the limbs of tetrapods (four-legged animals) and were the first step towards legs. Lobe-finned fish also have two dorsal fins (on their back) instead of one, unlike ray-finned fish. Many early lobe-finned fish had a symmetrical tail. All lobe-finned fish have teeth covered with real enamel.

Lobe-finned fish, like coelacanths and lungfish, were the most diverse group of bony fish in the Devonian. Scientists who classify animals by their family tree (cladistics) include Tetrapoda (all four-limbed vertebrates) within the lobe-finned fish group. The fins of lobe-finned fish, like the coelacanth, look very similar to what scientists believe were the first tetrapod limbs.

The first lobe-finned fish, found in the late Silurian (around 418 million years ago), looked a lot like spiny sharks. In the early-to-middle Devonian (416-385 million years ago), while armored placoderms ruled the seas, some lobe-finned fish moved into freshwater habitats.

In the Early Devonian (416-397 million years ago), lobe-finned fish split into two main groups: coelacanths and rhipidistians. Coelacanths stayed in the oceans and were most common in the Late Devonian and Carboniferous. Coelacanths still live in the oceans today. Rhipidistians, whose ancestors probably lived in estuaries, moved into freshwater. They then split into two groups: lungfish and tetrapodomorphs. Lungfish were most diverse in the Triassic period; today, fewer than a dozen types remain. Lungfish evolved the first simple lungs and limbs, allowing them to live outside water in the middle Devonian (397-385 million years ago). The first tetrapodomorphs, which included giant rhizodonts, had similar bodies to lungfish, but they seem to have stayed in water until the late Devonian (385-359 million years ago), when tetrapods (four-legged animals) appeared. Tetrapods are the only tetrapodomorphs that survived after the Devonian. Lobe-finned fish continued until the end of the Paleozoic era, suffering big losses during the Permian–Triassic extinction event (251 million years ago).

Ray-finned Fish: Modern Fish

Ray-finned fish are different from lobe-finned fish because their fins are made of skin supported by bony or horn-like spines ("rays"). They also have different breathing and blood circulation systems. Ray-finned fish usually have skeletons made of true bone, though some, like sturgeons and paddlefish, do not.

Ray-finned fish are the most common group of vertebrates, making up half of all known vertebrate species. They live in deep oceans, coastal areas, and freshwater rivers and lakes. They are a major food source for humans.

Timeline of Fish Evolution

Early Beginnings: Pre-Devonian Fish

| Cambrian | Cambrian (541–485 million years ago): The Cambrian began with the Cambrian explosion, where many invertebrate animal groups (like molluscs, jellyfish, worms, and arthropods) suddenly appeared. The first vertebrates, primitive fish, also appeared and later became very diverse in the Silurian and Devonian. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pikaia |

Pikaia, along with Myllokunmingia and Haikouichthys, are candidates for the "first vertebrate" and "first fish." Pikaia appeared about 530 million years ago during the Cambrian explosion. It is a transitional fossil between invertebrates and vertebrates, and might be the earliest known chordate. It was a simple creature, about 5 centimeters long, with no clear eyes or head. Pikaia was flat and swam by wiggling its body in S-shapes, similar to snakes. Fish inherited this swimming style, but with stiffer backbones. It had two large head tentacles and small parts that might be gill slits. Pikaia shows the basic features needed for vertebrates. Its body had segmented muscle blocks, and a flexible rod (notochord) ran from head to tail. |

||

| Haikouichthys | Haikouichthys (meaning "fish from Haikou") also appeared around 530 million years ago. It marks another step from invertebrates to vertebrates. Unlike Pikaia, it had eyes and a clear skull. These features led scientists to call it a true craniate, and one of the earliest fish. | ||

| Myllokunmingia | Myllokunmingia is another genus that appeared about 530 million years ago. It is a chordate, and some argue it is a vertebrate. It was 28 mm long and 6 mm high, making it one of the oldest possible craniates. | ||

| Conodonts | Conodonts (meaning "cone-teeth") looked like primitive eels. They appeared 495 million years ago and died out 200 million years ago. They were first known from tiny, tooth-like fossils. These "teeth" might have been for filter-feeding or for grasping food. Conodonts ranged from a centimeter to 40 cm long. Their large eyes were on the sides, suggesting they were not predators. Their muscles suggest some conodonts were good cruisers but couldn't swim fast. In 2012, scientists classified conodonts as chordates because of their fins with rays, V-shaped muscles, and a notochord. | ||

| Ostracoderms | Ostracoderms (meaning "shell-skinned") are groups of extinct, primitive, jawless fish covered in bony armor. They appeared in the Cambrian, about 510 million years ago, and died out near the end of the Devonian, about 377 million years ago. Early ostracoderms had simple fins, and paired fins (limbs) first evolved within this group. They were covered with bony armor or scales and were often less than 30 cm long. | ||

| Ordov- ician |

Ordovician (485–443 million years ago): Fish, the world's first true vertebrates, continued to evolve. Jawed fish (Gnathostomata) may have first appeared late in this period. Life had not yet diversified on land. | ||

| Arandaspis | Arandaspis was a jawless fish that lived in the early Ordovician period, about 480–470 million years ago. It was about 15 cm long, with a smooth body covered in rows of bumpy armored plates. The front of its body and head were protected by hard plates with openings for eyes, nostrils, and gills. Even though it was jawless, Arandaspis might have had movable plates in its mouth, like lips, to suck in food particles. Its low mouth suggests it fed on the ocean floor. It lacked fins, so it probably swam like a modern tadpole using its flat tail. | ||

| Astraspis | Astraspis (meaning "star shield") is an extinct group of primitive jawless fish related to other Ordovician fish like Sacabambaspis and Arandaspis. Fossils show clear evidence of a sensory system (lateral line system). This system allowed the fish to sense the direction and distance of disturbances in the water. Astraspis is thought to have had a movable tail covered with small protective plates and a head covered with larger plates. One specimen had relatively large eyes on the sides and eight gill openings on each side. | ||

| Pteraspidomorphi | Pteraspidomorphi is an extinct group of early jawless fish. Their fossils show extensive shielding of the head. Many had tails that helped them lift their armored bodies through the water. They also had sucking mouths, and some species may have lived in fresh water. | ||

| Thelodonts | Thelodonts (meaning "nipple teeth") are a group of small, extinct jawless fish with unique scales instead of large armor plates. There is debate about whether they are a single group or different groups that evolved similar scales. These scales were easily spread after death, and their small size makes them the most common vertebrate fossil from their time. These fish lived in both freshwater and marine environments, first appearing during the Ordovician and dying out during the Late Devonian extinction. They mostly fed on deposits on the bottom, but some might have lived in open water. | ||

| The Ordovician ended with the Ordovician–Silurian extinction event (450–440 million years ago). Two events caused the loss of many species. Many scientists rank this as the second largest of the five major extinctions in Earth's history. | |||

| Silurian | Silurian (443–419 million years ago): Many important evolutionary steps happened in this period, including the appearance of armored jawless fish, jawed fish, spiny sharks, and ray-finned fish. | ||

| While the Devonian is known as the age of fishes, recent discoveries show the Silurian also had a lot of fish diversification. Jawed fish developed movable jaws, which came from the supports of their front gill arches. | |||

| Anaspida | Anaspida (meaning "without shield") is an extinct group of primitive jawless vertebrates that lived during the Silurian and Devonian periods. They are often seen as ancestors of lampreys. Anaspids were small, mostly marine jawless fish that lacked heavy bony shields and paired fins, but had very exaggerated tails. They first appeared in the Early Silurian and thrived until the Late Devonian extinction, where most species, except for lampreys, died out. Unlike other jawless fish, anaspids did not have a bony shield or armor. Their heads were covered in smaller, weakly mineralized scales. | ||

| Osteostraci | Osteostraci (meaning "bony shields") were a group of bony-armored jawless fish that lived from the Middle Silurian to Late Devonian. Anatomically, osteostracans, especially Devonian species, were among the most advanced jawless fish. This is because they developed paired fins and complex skull anatomy. Most osteostracans had a large head shield. They were probably good swimmers, with dorsal fins, paired pectoral fins, and a strong tail. | ||

| Spiny sharks | Spiny sharks, also called "Acanthodians" (meaning "having spines"), are an extinct group of fish. They first appeared in the late Silurian, around 420 million years ago, and were among the first fish to evolve jaws. They share features with both cartilaginous fish and bony fish, but they are not true sharks, though they led to them. They died out before the end of the Permian, around 250 million years ago. Acanthodians were generally small, shark-like fish. They are unique because they were the earliest known jawed vertebrates, and they had strong spines supporting all their fins. These spines were fixed and couldn't move, like a shark's dorsal fin, and were an important defense. Their fossils are very rare. | ||

| Placoderms | Placoderms (meaning "plate-like skin") are a group of armored jawed fish. The oldest fossils appeared in the late Silurian, and they died out at the end of the Devonian. Recent studies suggest that placoderms are possibly a group of early jawed fish, and the closest relatives of all living jawed vertebrates. Some placoderms were small, flat bottom-dwellers. However, many, especially the arthrodires, were active predators in open water. Dunkleosteus, which appeared later in the Devonian, was the largest and most famous of these. Their upper jaw was firmly attached to the skull, but there was a hinge joint between the skull and the body armor. This allowed placoderms to lift their heads and take larger bites. | ||

| Megamastax | Megamastax (meaning "big mouth") is a group of lobe-finned fish that lived during the late Silurian period, about 423 million years ago, in China. Before Megamastax was discovered, it was thought that jawed vertebrates were small and not very diverse before the Devonian period. Megamastax is only known from jaw bones, and it is estimated to have been about 1 meter long. | ||

| Guiyu oneiros | Guiyu oneiros is the earliest known bony fish. It has features of both ray-finned and lobe-finned fish, though overall it is closer to lobe-finned fish. | ||

| Andreolepis | The extinct group Andreolepis includes the earliest known ray-finned fish, Andreolepis hedei, which appeared in the late Silurian, around 420 million years ago. | ||

The Age of Fish: Devonian Period

Axis scale: millions of years ago.

The Devonian Period is divided into Early, Middle, and Late Devonian. By the start of the Early Devonian (419 million years ago), jawed fish had split into four main groups: the placoderms and spiny sharks (both now extinct), and the cartilaginous and bony fish (both still alive today). Modern bony fish appeared in the late Silurian or early Devonian, about 416 million years ago. Both cartilaginous and bony fish may have come from either placoderms or spiny sharks. A group of bony fish, the ray-finned fish, became the most common fish group after the Paleozoic Era, with about 30,000 living species.

Sea levels in the Devonian were generally high. Ocean life was dominated by bryozoa, many different brachiopods, and corals. Lily-like crinoids were common, and trilobites were still around. Among vertebrates, jawless armored fish (ostracoderms) became less diverse, while jawed fish (gnathostomes) increased in both the sea and fresh water. Armored placoderms were numerous in the early Devonian but died out in the Late Devonian, perhaps because other fish competed for food. Early cartilaginous and bony fish also became diverse and played a big role in the Devonian seas. The first common type of shark, Cladoselache, appeared in the oceans during the Devonian Period. The great variety of fish at this time led to the Devonian being called "The Age of Fish."

The first ray-finned and lobe-finned bony fish appeared in the Devonian. Meanwhile, placoderms began to dominate almost every water environment. However, another group of bony fish, the Sarcopterygii (including lobe-finned fish like coelacanths and lungfish) and tetrapods, was the most diverse group of bony fish in the Devonian. Lobe-finned fish are known for their internal nostrils, lobe fins with strong internal skeletons, and cosmoid scales.

During the Middle Devonian (393–383 million years ago), armored jawless ostracoderm fish were declining. Jawed fish were thriving and becoming more diverse in both oceans and freshwater. The shallow, warm, low-oxygen waters of Devonian lakes, surrounded by early plants, provided the perfect environment for some early fish to develop important features like well-developed lungs and the ability to crawl onto land for short times. Cartilaginous fish, including sharks, rays, and chimaeras, appeared about 395 million years ago in the middle Devonian.

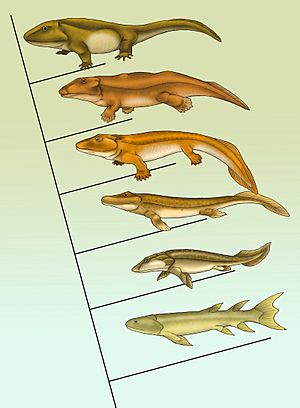

During the Late Devonian, the first forests were growing on land. The first tetrapods appeared in the fossil record during a period marked by extinction events. This lasted until the end of the Devonian, 359 million years ago. The ancestors of all tetrapods began adapting to walking on land. Their strong pectoral and pelvic fins slowly evolved into legs (see Tiktaalik). In the oceans, primitive sharks became more common than in the Silurian and late Ordovician. The first ammonite mollusks appeared. Trilobites, brachiopods, and large coral reefs were still common.

The Late Devonian extinction happened at the beginning of the last phase of the Devonian period, around 375 million years ago. Many fossil jawless fish disappeared just before this event. This extinction mainly affected ocean life, especially organisms in shallow, warm waters. The most affected group were the reef-builders of the large Devonian reef systems.

A second extinction event, the Hangenberg event, closed the Devonian period. It had a huge impact on vertebrates. Most placoderms became extinct during this event, as did most members of other groups like lobe-finned fish, acanthodians, and early tetrapods, both in water and on land. Only a few survivors remained. This event has been linked to ice ages in cold regions and low oxygen levels in the seas.

| Devonian (419–359 million years ago): The Devonian saw the first lobe-finned fish, which led to tetrapods (animals with four limbs). Many major fish groups evolved during this period, often called the age of fish. | ||||

| D e v o n i a n |

Early Devonian |

Early Devonian (419–393 million years ago): | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psarolepis | Psarolepis (meaning "speckled scale") is an extinct lobe-finned fish that lived around 397 to 418 million years ago. Fossils have been found mainly in South China. Scientists agree it is a very early type of fish, close to the common ancestor of lobe-finned and ray-finned fish. | |||

| Holoptychius | Holoptychius is an extinct lobe-finned fish that lived from 416 to 359 million years ago. It was a streamlined predator about 50 cm long (but could grow up to 2.5 m), feeding on other bony fish. Its rounded scales and body shape suggest it could swim fast. Like other rhipidistians, it had fang-like teeth on its palate, plus smaller teeth on its jaws. Its tail was asymmetrical, with a caudal fin on the lower end. To balance this, its pectoral fins were high on its body. | |||

| Ptyctodontida | The ptyctodontids (meaning "beak-teeth") are an extinct group of unarmored placoderms. They lived from the start to the end of the Devonian. With their big heads, big eyes, and long bodies, ptyctodontids looked a lot like modern chimaeras. Their armor was reduced to small plates around the head and neck. Like other extinct and living fish, most ptyctodontids likely lived near the seabed and ate shellfish. | |||

| Petalichthyida | The Petalichthyida was a group of small, flat placoderms that lived from the beginning to the Late Devonian. They had splayed fins and many bumps covering their armor plates and scales. They were most diverse in the Early Devonian and found worldwide. Because of their flat bodies, they are thought to have been bottom-dwellers that chased or ambushed smaller fish. Their diet is unclear, as no fossil mouth parts have been found. | |||

| Laccognathus | Laccognathus (meaning "pitted jaw") was a group of amphibious lobe-finned fish that lived 398–360 million years ago. They had three large pits on their lower jaw, which might have been for sensing. Laccognathus grew to 1-2 meters long. They had very short, flat heads. Their skeleton was very dense, making it unlikely they could breathe through their skin. Instead, this dense bone helped them keep water inside their bodies when they traveled on land between water bodies. | |||

| Middle Devonian |

Middle Devonian (393–383 million years ago): Cartilaginous fish, including sharks, rays, and chimaeras, appeared about 395 million years ago. | |||

| Dipterus | Dipterus (meaning "two wings") is an extinct lungfish from 376–361 million years ago. It was about 35 cm long, mostly ate invertebrates, and had lungs, not an air bladder. Like its ancestor, it had tooth-like plates instead of real teeth. Unlike modern lungfish, its fins were still separate. Otherwise, Dipterus looked very similar to modern lungfish. | |||

| Cheirolepis | Cheirolepis (meaning "hand fin") was a group of ray-finned fish. It was one of the earliest ray-finned fish in the Devonian and is considered the first to have the "standard" skull bones seen in later ray-finned fish. It was a predatory freshwater fish about 55 cm long, and its large eyes suggest it hunted by sight. | |||

| Cladoselache | Cladoselache was the first common type of primitive shark, appearing about 370 million years ago. It grew to 6 feet long, with features similar to modern mackerel sharks. It had a streamlined body with almost no scales, five to seven gill slits, and a short, rounded snout with a mouth at the front. Its jaw joint was weak compared to modern sharks, but it had very strong jaw muscles. Its teeth were multi-pointed and smooth, good for grasping but not tearing. Cladoselache probably grabbed prey by the tail and swallowed it whole. It had powerful keels on its tail and a semi-moon-shaped tail fin, which helped with speed and agility. This was useful for escaping its probable predator, the heavily armored 10-meter-long placoderm fish Dunkleosteus. | |||

| Coccosteus | Coccosteus (meaning "seed bone") is an extinct group of arthrodire placoderm. Most fossils have been found in freshwater, though they might have entered saltwater. They grew up to 40 cm long. Like all other arthrodires, Coccosteus had a joint between its body and skull armor. It also had an internal joint in its neck, allowing it to open its mouth even wider. This, along with longer jaws, allowed Coccosteus to eat fairly large prey. Like all other arthrodires, Coccosteus had bony dental plates in its jaws, forming a beak. The beak stayed sharp because its edges ground against each other. | |||

| Bothriolepis |

Bothriolepis (meaning "pitted scale") was the most successful group of antiarch placoderms, with over 100 species found across every continent from the Middle to Late Devonian. |

|||

| Pituriaspida | Pituriaspida is a group with two strange species of armored jawless fish that had huge, nose-like snouts. They lived in estuaries around 390 million years ago. One species looked like a throwing dart, with a long head shield and spear-like snout. The other looked like a guitar pick with a tail, with a smaller snout and a more triangular head shield. | |||

| Late Devonian extinction: 375–360 million years ago. A long series of extinctions wiped out about 19% of all families, 50% of all groups, and 70% to 75% of all species. This extinction event lasted perhaps as long as 20 million years, and there is evidence of several extinction pulses within this period. | ||||

| Late Devonian |

Late Devonian (383–359 million years ago): | |||

| Dunkleosteus |

Dunkleosteus is a group of arthrodire placoderms that lived from 380 to 360 million years ago. It grew up to 10 meters long and weighed up to 3.6 tons. It was a top predator that ate other animals. Besides its contemporary Titanichthys, no other placoderm was as big. Instead of teeth, Dunkleosteus had two pairs of sharp bony plates that formed a beak-like structure. It had one of the most powerful bites of any fish, similar to Tyrannosaurus rex and modern crocodiles. |

|||

| Titanichthys | Titanichthys is a group of giant, unusual marine placoderms that lived in shallow seas. Many species were similar in size to Dunkleosteus. However, unlike its relative, Titanichthys had small, weak-looking mouth-plates that lacked a sharp cutting edge. It is thought that Titanichthys was a filter feeder that used its large mouth to swallow or inhale schools of small, anchovy-like fish, or possibly krill-like zooplankton. The mouth-plates would have held the prey while allowing water to escape when it closed its mouth. | |||

| Materpiscis |

Materpiscis (meaning "mother fish") is a group of ptyctodontid placoderm from about 380 million years ago. It is unique because one specimen has an unborn embryo inside, with a preserved placental feeding structure (like an umbilical cord). This makes Materpiscis the first known vertebrate to give birth to live young. The specimen was named Materpiscis attenboroughi after David Attenborough. |

|||

| Hyneria | Hyneria is a group of predatory lobe-finned fish, about 2.5 meters long, that lived 360 million years ago. | |||

| Rhizodonts | Rhizodonts were a group of lobe-finned fish that survived until the end of the Carboniferous, 377–310 million years ago. They grew to huge sizes. The largest known species, Rhizodus hibberti, grew up to 7 meters long, making it the largest freshwater fish known. | |||

From Fish to Four-Legged Animals

The first tetrapods are four-legged, air-breathing land animals from which all land vertebrates, including humans, descended. They evolved from lobe-finned fish of the group Sarcopterygii. They appeared in coastal waters in the middle Devonian and gave rise to the first amphibians.

The group of lobe-finned fish that were ancestors of tetrapods are called Rhipidistia. The first tetrapods evolved from these fish over a relatively short time, 385–360 million years ago. The early tetrapod groups are called Labyrinthodontia. They kept aquatic, tadpole-like young, a system still seen in modern amphibians.

From the 1950s to the early 1980s, it was thought that tetrapods evolved from fish that could already crawl on land, perhaps to move between drying pools. However, in 1987, nearly complete fossils of Acanthostega from about 363 million years ago showed that this Late Devonian transitional animal had legs, lungs, and gills, but could not have survived on land. Its limbs and joints were too weak to support its weight, and its ribs were too short to prevent its lungs from being crushed. Its fish-like tail fin would have been damaged by dragging on the ground.

The current idea is that Acanthostega, which was about 1 meter long, was a water predator that hunted in shallow water. Its skeleton was different from most fish in ways that allowed it to raise its head to breathe air while its body stayed underwater. For example, its jaws could gulp air, and the bones at the back of its skull were locked together, providing strong attachment points for muscles that raised its head. Its head was not joined to its shoulder, giving it a distinct neck.

The increase in land plants during the Devonian might explain why air-breathing was helpful. Leaves falling into streams would have encouraged aquatic plants to grow. This would attract grazing invertebrates and small fish that ate them. These would be attractive prey, but the water would have had low oxygen because warm water holds less oxygen, and decaying plants use up oxygen. Air-breathing would have been necessary in these conditions.

There are different ideas about how tetrapods evolved their stubby fins (proto-limbs). The traditional idea is the "shrinking waterhole hypothesis" or "desert hypothesis." This suggests that limbs and lungs evolved because fish needed to find new water bodies as old ones dried up.

A second idea, the "inter-tidal hypothesis," suggests that lobe-finned fish first came onto land from intertidal zones (areas covered and uncovered by tides) rather than inland waters. This idea is based on 395-million-year-old fossil tracks found in Poland, the oldest evidence of tetrapods.

A third idea, the "woodland hypothesis," suggests that limbs developed in shallow waters in woodlands. These limbs would have helped fish move through environments filled with roots and plants. This idea is based on the fact that transitional tetrapod fossils are often found in places that were once humid, wooded floodplains.

Research by Jennifer A. Clack and her team showed that the very earliest tetrapods, like Acanthostega, were fully aquatic and not suited for life on land. This goes against the earlier idea that fish first invaded land (like modern mudskippers) and then evolved legs and lungs.

For a long time, scientists debated whether fingers and toes were new features in tetrapods or if their basic parts were already in the fins of early lobe-finned fish. Recently, a 3D reconstruction of Panderichthys, a coastal fish from the Devonian (385 million years ago), showed that these animals already had many of the same bones found in the front limbs of vertebrates. For example, they had radial bones similar to simple fingers, but located in the arm-like base of their fins. This suggests that in the evolution of tetrapods, the outer part of the fins was lost and replaced by early digits.

From the end of the Devonian to the Mid Carboniferous, there is a 30-million-year gap in the fossil record. This gap, called Romer's gap, is missing fossils of early tetrapods and other vertebrates that looked well-adapted for land.

| Key Steps from Lobe-finned Fish to Tetrapods | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ~385 million years ago | Eusthenopteron |

This group of extinct lobe-finned fish is famous for its close link to tetrapods. Early drawings showed it coming onto land, but scientists now agree it was strictly aquatic. Eusthenopteron lived during the Late Devonian, about 385 million years ago. |

|

| Gogonasus | Gogonasus (meaning "snout from Gogo") was a lobe-finned fish known from 3D fossils from 380 million years ago. It was a small fish, 30-40 cm long. Its skeleton shows several tetrapod-like features, including its middle ear structure. Its fins show the early forms of forearm bones (radius and ulna). Scientists believe it used its forearm-like fins to dart out of the reef to catch prey. Gogonasus is now considered a better example than Eusthenopteron for showing stages in the evolution from lobe-finned fish to tetrapods. | ||

|

~385 million years ago |

Panderichthys | This fish was adapted to muddy, shallow waters and could move its body in a flexible way in shallow water or on land. It could prop itself up. They had large, tetrapod-like heads and are thought to be the most advanced fish-tetrapod ancestor with paired fins. | |

|

~375 million years ago |

Tiktaalik | This fish had limb-like fins that could take it onto land. It is an example of ancient lobe-finned fish developing adaptations for low-oxygen, shallow-water habitats. This led to the evolution of tetrapods. Scientists suggest it represents the transition between fish like Panderichthys (380 million years old) and early tetrapods like Acanthostega and Ichthyostega (about 365 million years old). Its mix of fish and tetrapod features led one of its discoverers to call Tiktaalik a "fishapod". | |

|

365 million years ago |

Acanthostega | This fish-like early labyrinthodont lived in swamps and changed how scientists viewed early tetrapod evolution. It had eight digits on each hand, connected by webbing. It lacked wrists and was not well-suited for land. Later discoveries showed even earlier transitional forms between Acanthostega and fully fish-like animals. | |

|

374–359 million years ago |

Ichthyostega |

Until other early tetrapods and related fish were found in the late 20th century, Ichthyostega was the main transitional fossil between fish and tetrapods. It had a fish-like tail and gills, but an amphibian skull and limbs. It had lungs and limbs with seven digits that helped it move through shallow swamp water. |

|

|

359–345 million years ago |

Pederpes | Pederpes is the earliest known fully land-dwelling tetrapod. It is included here to show the complete transition from lobe-finned fish to tetrapods, even though Pederpes is no longer a fish. | |

By the late Devonian, land plants had made freshwater habitats more stable. This allowed the first wetland ecosystems to develop, with more complex food webs that offered new opportunities. Swampy areas like shallow wetlands, coastal lagoons, and large river deltas also existed. There is much evidence that tetrapods evolved in these environments. Early fossil tetrapods have been found in marine sediments. Since primitive tetrapod fossils are found worldwide, they must have spread along coastlines, not just in freshwater.

Fish After the Devonian

- During the Carboniferous period, fish diversity seemed to decrease, reaching low levels in the Permian period.

- The Mesozoic Era began about 252 million years ago after the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the largest mass extinction in Earth's history. It ended about 66 million years ago with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, which killed off non-avian dinosaurs and many other species. The Mesozoic is often called the Age of Reptiles because reptiles were the main vertebrates. During this time, the supercontinent Pangaea slowly broke apart. The climate changed between warm and cool periods, but overall Earth was hotter than today. Bony fish were mostly unaffected by the Permian-Triassic extinction event.

- The Mesozoic saw the diversification of neopterygian fish, which include holostean and teleost fish. Most of them were small. The variety of body shapes in Triassic, Jurassic, and Early Cretaceous neopterygian fish shows that new body shapes in teleost fish appeared gradually over 150 million years (250-100 million years ago). Holostean fish seemed to gain body shape variety between the early Triassic and Toarcian stages. After that, their body shape variety stayed stable until the end of the Early Cretaceous.

| Carbon- iferous |

Carboniferous (359–299 million years ago): Sharks underwent a major period of evolution during the Carboniferous. This happened because the decline of placoderms at the end of the Devonian left many environmental niches empty, allowing new organisms to evolve and fill them. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal seas during the Carboniferous: The first 15 million years of the Carboniferous have very few land fossils. This gap, called Romer's gap, is named after the American paleontologist Alfred Romer. While debated, recent work suggests this gap saw a drop in atmospheric oxygen, indicating an ecological collapse. This period saw the end of the Devonian fish-like labyrinthodonts and the rise of more advanced amphibians that are typical of Carboniferous land vertebrates.

The Carboniferous seas had many fish, mainly Elasmobranchs (sharks and their relatives). Some, like Psammodus, had crushing teeth for grinding shells of brachiopods and crustaceans. Other sharks had piercing teeth, and some had unique cutting teeth. Most sharks were marine, but some invaded freshwater swamps. Among bony fish, ray-finned fish found in coastal waters also seem to have moved to rivers. Lobe-finned fish were also common, and one group, the Rhizodonts, grew very large. Most Carboniferous marine fish species are known from teeth, fin spines, and skin bones, while smaller freshwater fish are preserved whole. Freshwater fish were abundant, including Ctenodus, Uronemus, Acanthodes, Cheirodus, and Gyracanthus. |

|||

| Stethacanthus |

As a result of evolution, Carboniferous sharks took on many strange shapes. This included sharks of the family Stethacanthidae, which had a flat, brush-like dorsal fin with a patch of denticles (small, tooth-like scales) on top. Stethacanthus' unusual fin might have been used in mating rituals. Besides the fins, Stethacanthidae looked like Falcatus (below). |

||

| Falcatus | Falcatus is a group of small, cladodont-toothed sharks that lived 335–318 million years ago. They were about 25–30 cm long. They are known for the prominent fin spines that curved forward over their heads. | ||

| Belantsea | Belantsea is an example of the Carboniferous to Permian group Petalodontiformes. Petalodontiforms are known for their unique teeth. The group died out in the late Permian. One of the last survivors was Janassa, which looked like modern rays, though it is not closely related to them. | ||

| Orodus | Orodus is another shark from the Carboniferous, a group that lived into the early Permian from 303 to 295 million years ago. It grew to 2 meters long. | ||

| Chondrenchelys | Chondrenchelys is an extinct group of cartilaginous fish from the Carboniferous period. It had a long, eel-like body. Chondrenchelys is a holocephalan and a distant relative of modern ratfishes. | ||

| Edestus |

Edestus is a group from the extinct Eugeneodontida order, a group of cartilaginous fish related to modern chimerids (ratfishes). Other Carboniferous groups include Bobbodus, Campodus, and Ornithoprion. Eugeneodontids were common during the Carboniferous period. Members of this order typically had tooth whorls, mostly formed by their lower jaws. In Edestus, both the upper and lower jaws formed a tooth whorl. Some species of Edestus could reach body lengths of 6.7 meters. |

||

| Permian | Permian (298–252 million years ago): | ||

| Helicoprion |

Helicoprion is perhaps the most famous group of the extinct Eugeneodontida. This group of cartilaginous fish is related to modern chimerids (ratfishes). Eugeneodontids disappeared during the Permian period, with only a few groups surviving into the earliest Triassic (Caseodus, Fadenia). Typically, members of this group had tooth whorls. Species of Helicoprion could reach between 5 meters and 8 meters in size. |

||

| Triodus | Triodus is a group of xenacanthid cartilaginous fish. The order Xenacanthida existed during the Carboniferous to Triassic period, and is well known from many complete skeletons from the early Permian. They typically had a prominent dorsal fin spine. Xenacanthids were fierce freshwater predators. | ||

| Acanthodes | Acanthodes is an extinct group of spiny shark. It had gills but no teeth, and was likely a filter feeder. Acanthodes had only two skull bones and were covered in cubical scales. Each pair of pectoral and pelvic fins had one spine, as did the single anal and dorsal fins, giving it a total of six spines, less than half that of many other spiny sharks. Acanthodians share qualities of both bony fish and cartilaginous fish. Spiny sharks became extinct in the Permian. | ||

| Palatinichthys | Megalichthyids are an extinct family of lobe-finned fish. They are tetrapodomorphs, a group of lobe-finned fish closely related to land-living vertebrates. Megalichthyids survived into the Permian but became extinct during this period. Palatinichthys from the early Permian of Germany was one of the last survivors of this group. | ||

| Acrolepis | Acrolepis is a group of palaeoniscoid ray-finned fish that existed during the Carboniferous to Triassic period. It had long jaws and its eyes were at the front of the skull. Acrolepis had a heterocercal tail fin and a spindle-shaped body. Its body was covered in thick ganoid scales. This body shape is typical for many late Paleozoic ray-finned fish. | ||

| The Permian ended with the largest extinction event ever recorded: the Permian–Triassic extinction event. 90% to 95% of marine species became extinct, as well as 70% of all land organisms. It is also the only known mass extinction of insects. Recovery from this event was slow; land ecosystems took 30 million years to recover, and marine ecosystems took even longer. However, bony fish were mostly not affected by this extinction event. | |||

| Triassic | Triassic (252–201 million years ago): The fish of the Early Triassic were very similar worldwide. This shows that the surviving families spread globally after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Many new types of ray-finned fish appeared during the Triassic, setting the stage for many modern fish. | ||

| Foreyia |

The Middle Triassic Foreyia, along with Ticinepomis, is one of the earliest known members of the family Latimeriidae, which also includes the living coelacanth Latimeria. Foreyia had an unusual body shape for a coelacanth, a group known for their unchanging body plan. Rebellatrix is another Triassic coelacanth with an unusual shape. This group had a forked tail fin, suggesting it was a fast swimmer. Coelacanths had one of their highest diversities after the Devonian during the Early Triassic. |

||

| Saurichthys |

Saurichthyiformes are an extinct group of ray-finned fish that evolved shortly before the Permian–Triassic extinction event and quickly diversified after it. The Triassic group Saurichthys includes over 50 species, some reaching up to 1.5 meters long. Some Middle Triassic species show evidence of giving birth to live young, with embryos preserved in females and male reproductive organs. This is the earliest known case of a ray-finned fish giving birth to live young. Saurichthys was also the first ray-finned fish to show adaptations for ambush hunting. |

||

| Perleidus |

Perleidus was a ray-finned fish from the Middle Triassic. About 15 cm long, it was a marine predatory fish with jaws that hung vertically, allowing them to open wide. The Triassic Perleidiformes were very diverse in shape and had specialized teeth for feeding. Colobodus, for example, had strong, button-like teeth. Some perleidiforms, like Thoracopterus, were the first ray-finned fish to glide over water, much like modern flying fish, though they are only distantly related. |

||

| Robustichthys | Robustichthys is a Middle Triassic ionoscopiform ray-finned fish. They belong to the group Halecomorphi, which were once diverse during the Mesozoic Era, but today are represented by only one species, the bowfin. Halecomorphs are holosteans, a group that first appeared in the fossil record during the Triassic. | ||

| Semionotus |

Semionotiformes are an extinct group of holostean ray-finned fish that existed during the Mesozoic Era. They were known for their thick scales and specialized jaws. They are relatives of modern gars, both belonging to the group Ginglymodi. This group first appears in the fossil record during the Triassic. Once diverse, they are only represented by a few species today. |

||

| Pholidophorus | Pholidophorus was an extinct group of teleost fish, about 40 cm long, from about 240–140 million years ago. Although not closely related to modern herring, it was somewhat similar. It had a single dorsal fin, a symmetrical tail, and an anal fin placed towards the rear. It had large eyes and was probably a fast-swimming predator, hunting tiny crustaceans and smaller fish. A very early teleost, Pholidophorus had many primitive features like ganoid scales and a spine that was partly made of cartilage, not just bone. Teleosts first appeared in the fossil record during the Triassic. One of the earliest members is Prohalecites. | ||

| The Triassic ended with the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event. About 23% of all families, 48% of all groups (20% of marine families and 55% of marine groups), and 70% to 75% of all species became extinct. Ray-finned fish, however, were mostly unaffected by this extinction event. Non-dinosaurian archosaurs continued to dominate water environments, while non-archosaurian diapsids continued to dominate marine environments. | |||

| Jurassic | Jurassic (201–145 million years ago): During the Jurassic period, the main vertebrates in the seas were fish and marine reptiles. Reptiles included ichthyosaurs (at their peak), plesiosaurs, pliosaurs, and marine crocodiles. Many turtles could be found in lakes and and rivers. | ||

| Pachycormiformes |

Pachycormiformes are an extinct group of ray-finned fish that lived from the Early Jurassic to the K-Pg extinction (below). They were known for their serrated pectoral fins, small pelvic fins, and a bony snout. Their relationship with other fish is unclear. |

||

| Leedsichthys | Along with its close relatives Bonnerichthys and Rhinconichthys, Leedsichthys is part of a group of large filter-feeding fish that swam the Mesozoic seas for over 100 million years, from the middle Jurassic until the end of the Cretaceous period. These fish might be an early branch of Teleostei, the group most modern bony fish belong to. If so, Leedsichthys is the largest known teleost fish. In 2003, a fossil specimen 22 meters (72 feet) long was found. | ||

| Ichthyodectidae |

The family Ichthyodectidae (meaning "fish-biters") was a family of marine ray-finned fish. They first appeared 156 million years ago during the Late Jurassic and disappeared during the K-Pg extinction event 66 million years ago. They were most diverse throughout the Cretaceous period. Most ichthyodectids were between 1 and 5 meters long. All known types were predators, feeding on smaller fish. In some cases, larger Ichthyodectidae ate smaller members of their own family. Some species had very large teeth, though others, like Gillicus arcuatus, had small ones and sucked in their prey. The largest Xiphactinus was 20 feet long and appeared in the Late Cretaceous (below). |

||

| Cret- aceous |

Cretaceous (145–66 million years ago): | ||

| Sturgeon | True sturgeons appear in the fossil record during the Upper Cretaceous. Since then, sturgeons have changed very little in their body shape, showing their evolution has been very slow. This has earned them the informal status of living fossils. This is partly because they live a long time, can handle wide ranges of temperature and saltiness, have few predators due to their size, and have plenty of food on the ocean floor. | ||

| Cretoxyrhina | Cretoxyrhina mantelli was a large shark that lived about 100 to 82 million years ago, during the mid-Cretaceous period. It is commonly known as the Ginsu Shark.

This shark was first identified by the famous Swiss Naturalist, Louis Agassiz in 1843. However, the most complete specimen was found in 1890 by fossil hunter Charles H. Sternberg, who published his findings in 1907. The specimen included a nearly complete backbone and over 250 teeth. This kind of excellent preservation of fossil sharks is rare because a shark's skeleton is made of cartilage, which doesn't fossilize easily. Charles called the specimen Oxyrhina mantelli. This specimen was a 20-foot-long shark. |

||

| Enchodus | Enchodus is an extinct group of bony fish. It was common during the Upper Cretaceous and was small to medium in size. One of its most notable features is the large "fangs" at the front of its upper and lower jaws and on its palate bones. This led to its nickname, "the saber-toothed herring." These fangs, along with a long, sleek body and large eyes, suggest Enchodus was a predatory species. | ||

| Xiphactinus |

Xiphactinus is an extinct group of large predatory marine bony fish from the Late Cretaceous. They grew more than 4.5 meters long. |

||

| Ptychodus | Ptychodus is a group of extinct hybodontiform shark that lived from the late Cretaceous to the Paleogene. Ptychodus mortoni (pictured) was about 32 feet long and was found in Kansas, United States. | ||

| The end of the Cretaceous was marked by the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (K-Pg extinction). There are many fossils of jawed fish across this boundary, showing how these marine vertebrates were affected. Among cartilaginous fish, about 80% of shark, ray, and skate families survived. More than 90% of teleost fish (bony fish) families survived. There is evidence of a mass death of bony fish at a fossil site near Antarctica right above the K-T boundary layer, likely caused by the K-Pg extinction event. However, the marine and freshwater environments helped fish survive the environmental effects. Evidence shows a major increase in the size and number of teleosts right after the extinction, likely because their ammonite competitors were gone (sharks didn't show a similar change). | |||

| Cenozoic Era |

Cenozoic Era (66 million years ago to present): The current era has seen many new types of bony fish. Over half of all living vertebrate species (about 32,000 species) are fish. They live in all water environments, from snow minnows in Himalayan lakes (over 4,600 meters high) to flatfish in the Challenger Deep (about 11,000 meters deep). Fish are the main predators in most of the world's water bodies, both freshwater and marine. | ||

| Amphistium | Amphistium is a 50-million-year-old fossil fish that has been identified as an early relative of the flatfish, and a transitional fossil. In a typical modern flatfish, the head is uneven, with both eyes on one side. In Amphistium, the change from a normal symmetrical head is incomplete, with one eye placed near the top of the head. | ||

| Megalodon |

Megalodon is an extinct species of shark that lived about 28 to 1.5 million years ago. It looked much like a very strong version of the great white shark, but was much larger, with fossil lengths reaching 20.3 meters. Found in all oceans, it was one of the largest and most powerful predators in vertebrate history, and likely had a big impact on marine life. |

||

Prehistoric Fish

Prehistoric fish are early fish known only from fossil records. They are the earliest known vertebrates. This group includes the first and extinct fish that lived from the Cambrian to the Tertiary periods. The study of prehistoric fish is called paleoichthyology. A few living types, like the coelacanth, are also called prehistoric fish or living fossils because they are rare today and look similar to extinct forms. Fish that have recently become extinct are usually not called prehistoric fish.

Living Fossils

Jawless Fish

Bony Fish

- Arowana and Arapaima

- Bowfin

- Coelacanth

- Gar

- Queensland lungfish

- Protanguilla palau (eel)

- Sturgeons and paddlefish

- Bichir

Sharks

The coelacanth was thought to have died out 66 million years ago, until a living one was found in 1938 off the coast of South Africa.

Fossil Sites

Some fossil sites that have produced important fish fossils:

- Abbey Wood SSSI

- Besano Formation

- Bracklesham Beds

- Bear Gulch Limestone

- Burgess Shale

- Canowindra

- Cleveland Shale

- Crato Formation

- Dura Den

- Feltville Formation

- Fossil Butte National Monument

- Fur Formation

- Gogo Formation

- Green's Creek

- Green River Formation

- Guanling Formation

- Kakwa Provincial Park

- Land Grove Quarry

- Maotianshan Shales

- Matanuska Formation

- McAbee Fossil Beds

- Miguasha National Park

- MoClay

- Monte Bolca

- Mount Ritchie

- Orcadian Basin

- Posidonia Shale

- Portishead Pier to Black Nore SSSI

- Santana Formation

- Southerham Grey Pit

- Thanet Formation

- Towaco Formation

- Weydale

- Zhoukoudian

Paleoichthyologists

Paleoichthyology is the scientific study of prehistoric fish life. Here are some researchers who have made important contributions to this field:

- Louis Agassiz

- Mary Anning

- Michael Benton

- Derek Briggs

- Hans C. Bjerring

- John Samuel Budgett

- Henri Cappetta

- Meemann Chang

- Frederick Chapman

- Jenny Clack

- Ted Daeschler

- Bashford Dean

- Robert Dick

- Philip Grey Egerton

- Brian G. Gardiner

- Sam Giles

- Lance Grande

- Edwin Sherbon Hills

- Jeffrey A. Hutchings

- Thomas Henry Huxley

- Johan Aschehoug Kiær

- Philippe Janvier

- Erik Jarvik

- George V. Lauder

- John A. Long

- Hugh Miller

- Charles Moore

- Paul E. Olsen

- Heinz Christian Pander

- Elizabeth Philpot

- Jean Piveteau

- Colin Patterson

- Alfred Romer

- Ira Rubinoff

- Lauren Sallan

- Neil Shubin

- Franz Steindachner

- Erik Stensiö

- Ramsay Heatley Traquair

- Thomas Stanley Westoll

- Tiberius Cornelis Winkler

- Arthur Smith Woodward

Images for kids

-

†Placoderms (extinct) were armored jawed fish.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |