Helicoprion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Helicoprion |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Tooth-whorl, Utah Field House of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | †Eugeneodontida |

| Family: | †Helicoprionidae |

| Genus: | †Helicoprion Karpinsky, 1899 |

| Type species | |

| Helicoprion bessonowi Karpinsky, 1899

|

|

| Species | |

|

|

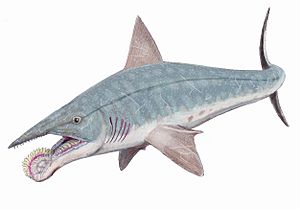

Helicoprion was an extinct fish that looked a bit like a shark. It lived in the oceans about 290 million years ago during the Early Permian period. Scientists have found its fossils in places like North America, Eastern Europe, Asia, and Australia.

What made Helicoprion special was its amazing set of teeth. Almost all the fossils we find are of a spiral-shaped group of teeth, called a "tooth whorl". This tooth whorl was located in its lower jaw. Because Helicoprion was a cartilaginous fish (meaning its skeleton was made of cartilage, not bone), most of its body didn't turn into fossils.

The closest living relatives of Helicoprion today are the chimaeras, which are also a type of cartilaginous fish. Scientists think the unique tooth whorl helped Helicoprion catch soft prey. It might have also helped it crush the shells of hard-bodied cephalopods like nautiloids and ammonoids.

Contents

Discovering the Ancient Helicoprion

The first Helicoprion fossil was a small tooth whorl found in Western Australia. Henry Woodward described it in 1886. At first, he thought it belonged to a different animal called Edestus.

In 1899, Alexander Karpinsky officially named Helicoprion. He found six tooth whorls in the Ural Mountains. He named the main species Helicoprion bessonowi. Karpinsky also realized that the Australian fossil was actually a Helicoprion, so he renamed it Helicoprion davisii.

Over the years, more Helicoprion fossils were found. These discoveries happened in places like Idaho, Wyoming, California, and Nevada in North America. Fossils were also found in Mexico, China, and Svalbard, Norway. More than half of all known Helicoprion fossils come from Idaho.

How Scientists Thought Helicoprion Looked

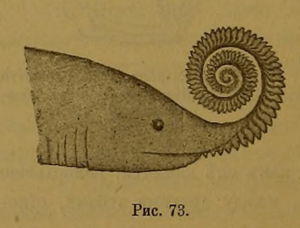

For a long time, scientists weren't sure exactly where the tooth whorl was located. Some early drawings showed it at the very front of the lower jaw. It looked like a circular saw sticking out!

It wasn't until a related fish, Ornithoprion, was discovered that scientists understood the tooth whorl was inside the lower jaw. The whorl held all the teeth an individual Helicoprion ever grew. As the fish got older, new, larger teeth pushed the older, smaller ones into the center of the spiral.

In 1994, author Brad Matsen and artist Ray Troll suggested that Helicoprion might not have had any teeth in its upper jaw. They thought the tooth whorl in the lower jaw would cut against crushing plates in the upper jaw. They imagined Helicoprion having a long, narrow head, similar to a modern-day goblin shark.

Later, in 2008, a new reconstruction by the Smithsonian placed the tooth whorl deeper inside the throat. However, other studies didn't agree with this idea.

What Helicoprion Looked Like

The Amazing Tooth Whorls

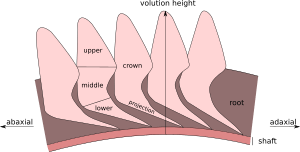

Most of what we know about Helicoprion comes from its unique "tooth whorls." These whorls are made of dozens of teeth arranged in a spiral shape. The teeth are set into a root made of a special bone-like material called osteodentine.

The very first tooth a young Helicoprion had was hooked. But as it grew, the adult teeth became triangular and often had serrated (saw-like) edges. These teeth pointed forward in the spiral. The tooth whorl was like a growth ring for the fish. Each new set of teeth pushed the older ones further into the spiral.

Its Cartilaginous Skull

Since Helicoprion was a cartilaginous fish, its skeleton was made of cartilage. Cartilage usually breaks down quickly after an animal dies. This means we rarely find complete skeletons.

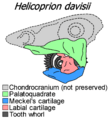

However, one amazing Helicoprion fossil (IMNH 37899) was found in Idaho in 1950. This fossil was so well-preserved that scientists could study parts of its cartilaginous skull. Using CT scans, they saw the upper and lower jaw cartilage, along with the tooth whorl.

The upper jaw had no teeth. The lower jaw's cartilage had a part that fit against the upper jaw. This might have stopped the tooth whorl from poking through the upper jaw. This study, from 2013, showed the tooth whorl was located at the back of the jaw. It filled almost the entire lower jaw arch.

Main Helicoprion Species

H. bessonowi

Helicoprion bessonowi is the first and most famous species of Helicoprion. Alexander Karpinsky described it in 1899. This species has a tooth whorl that is short and has teeth close together. The tips of its teeth point backward, and the bases of the teeth are wide.

Another species, H. nevadensis, was described in 1939. However, later studies showed that its features were very similar to H. bessonowi. So, scientists now think it's the same species.

H. svalis, found in Norway, was described in 1970. It has a very large tooth whorl. While it's hard to be completely sure, many of its features are very similar to H. bessonowi.

H. davisii

H. davisii was first found in Western Australia in 1886. It was initially thought to be a different type of fish. But Karpinsky later moved it to the Helicoprion group.

This species has a tall tooth whorl with teeth that are spaced far apart. These features become even clearer as the fish gets older. Its teeth also curve noticeably forward. H. davisii was very common around the world during the middle Permian period.

H. ferrieri was another species described in 1907 from fossils in Idaho. Later, scientists realized that its features were just variations seen within H. davisii. So, H. ferrieri is now considered to be the same as H. davisii.

H. jingmenense, found in China in 2007, was also very similar to H. davisii. After careful study, scientists decided it was also the same species.

H. ergassaminon

H. ergassaminon is a rarer species found in Idaho. It was described in detail in 1966. The original fossil showed signs of wear, suggesting it was used for feeding.

This species is somewhat in between H. bessonowi and H. davisii. It has tall teeth, but they are spaced closely together. Its teeth also have a gentle curve and wide bases.

Images for kids

-

IMNH 30900, a Helicoprion ergassaminon tooth-whorl from Gay Mine in Bingham County, Idaho.

See also

In Spanish: Helicoprion para niños

In Spanish: Helicoprion para niños