Ray Lankester facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

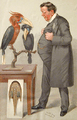

Sir E. Ray Lankester

|

|

|---|---|

Sir E. Ray Lankester in 1908

|

|

| Born | 15 May 1847 London, England

|

| Died | 13 August 1929 (aged 82) London, England

|

| Alma mater | Downing College, Cambridge Christ Church, Oxford |

| Known for | Evolution, Rationalism |

| Awards | Knight Bachelor (1906) Darwin-Wallace Medal (Silver, 1908) Copley Medal (1913) Linnean Medal (1920) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Zoology |

| Institutions | University College London Oxford University British Museum (Natural History) |

| Influences | Thomas Henry Huxley, August Weismann, Anton Dohrn |

| Influenced | E. S. Goodrich Raphael Weldon |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Lank. |

Sir Edwin Ray Lankester (born May 15, 1847 – died August 13, 1929) was an important British zoologist. He studied animals, especially those without backbones, and how living things change over time.

He taught at famous universities like University College London and Oxford University. He also led the Natural History Museum, London for a time. He received many awards for his work, including the Copley Medal.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Ray Lankester was born in London on May 15, 1847. His father, Edwin Lankester, was a doctor and naturalist who helped stop cholera in London. His mother, Phebe Lankester, was a botanist and writer. Ray was likely named after the famous naturalist John Ray.

He went to boarding school and then to St Paul's School. For university, he studied at Downing College, Cambridge and later at Christ Church, Oxford. He chose Oxford because it had better teachers for his chosen field.

Ray Lankester finished his studies with top honors in 1868. He also traveled to places like Vienna, Leipzig, and Jena to learn more. He even worked at a special marine biology station in Naples, Italy. He studied under Thomas Henry Huxley, a very famous scientist of his time.

Ray Lankester had a much better education than many scientists before him. His father's friends, who included famous people like Charles Darwin and Joseph Dalton Hooker, also influenced him greatly.

He was a big man with a strong personality. He admired Abraham Lincoln and was known for speaking his mind, sometimes a bit too forcefully. This directness sometimes caused problems in his career.

Ray Lankester never married. He passed away in London on August 13, 1929. You can find a special memorial plaque for him at the Golders Green Crematorium in London.

Career and Discoveries

In 1873, Lankester became a Fellow at Exeter College, Oxford. He helped edit the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, a science magazine his father started.

From 1874 to 1890, he was a professor at University College London. He then moved to Oxford University, where he taught from 1891 to 1898. After that, he became the director of the Natural History Museum, London from 1898 to 1907.

He also helped start the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom in 1884, which studies sea life. He was its president for many years.

Lankester was a very influential teacher and writer. He studied protozoa (tiny single-celled organisms), mollusca (like snails and clams), and arthropoda (like insects and crabs). He was knighted in 1907 and received several important awards for his scientific work.

Influential Teacher

At University College London, Lankester taught many students who became important scientists themselves. One of them was Raphael Weldon, who later took over Lankester's teaching position. Weldon is known for helping to create the science of biometry, which uses statistics to study biology.

Lankester was greatly influenced by August Weismann, a German zoologist. Weismann believed strongly in natural selection as the main way evolution happens. He also had an important idea about germplasm (the genetic material passed down) being separate from the rest of the body. Lankester was one of the first to understand how important this idea was. He even translated some of Weismann's writings into English.

Lankester's teaching had a huge impact. He helped create a group of scientists at Oxford who believed in natural selection. His students and their students went on to make big discoveries in fields like ecological genetics and marine biology.

Studying Invertebrates

As a zoologist, Lankester focused on comparing the bodies of different animals, especially invertebrates (animals without backbones). He was the first to show that the horseshoe crab was related to Arachnida (spiders and scorpions). You can still see his horseshoe crab specimens at the Grant Museum of Zoology in London today.

He also wrote many books and articles about biology for the general public, just like his mentor, Thomas Huxley. He published over 200 scientific papers.

Evolution and Degeneration

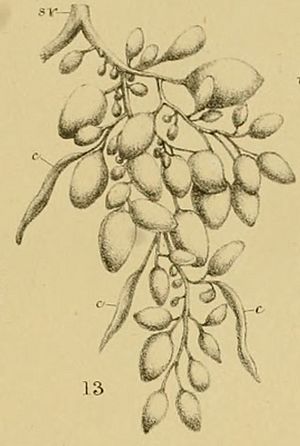

Lankester wrote important books like Developmental history of the Mollusca (1875) and Degeneration: a chapter in Darwinism (1880). In Degeneration, he explored the idea that evolution doesn't always lead to more complex forms. Sometimes, animals can become simpler over time, a process he called "degeneration."

He explained that if an animal finds food and safety easily, it might lose some of its features. This is common in parasites. For example, the female Sacculina, a barnacle that lives on crabs, becomes little more than a "sac of eggs" that absorbs food from the crab. Lankester called this retrogressive metamorphosis.

He also pointed out that this "degeneration" can happen when species adapt to new ways of life. For example, some lizards have tiny limbs, and snakes have no legs at all, likely because they adapted to burrowing or slithering.

Lankester also studied the axolotl, a type of salamander that can breed while still in its larval (young) form. He called this super-larvation, which is now known as neoteny. This means that sometimes, a species can evolve in a completely new direction by keeping its young features.

Trouble at the Museum

When Lankester became the director of the Natural History Museum, London in 1898, it was part of the British Museum. This meant the museum's director had to report to the head of the British Museum, who was not a scientist. This caused a lot of conflict.

Lankester wanted to make the Natural History Museum more independent and improve it. However, the head of the British Museum, Sir Edward Maunde Thompson, often got in his way. After eight years of disagreements, Lankester resigned in 1907. Thompson used a rule that allowed him to ask officials to resign at age 60.

Many people, including scientists from other countries, were upset about how Lankester was treated. However, Lankester still had powerful friends. He was offered a better pension and was knighted the next year.

This conflict eventually led to the Natural History Museum becoming completely separate from the British Museum. Today, the British Library, the British Museum, and the Natural History Museum are all independent.

Rationalism and Public Science

Lankester was part of a group called the Rationalists, who believed in using reason and science to understand the world. He was friends with other rationalist thinkers like Thomas Huxley.

He was also very interested in early human history and supported the idea that some very old stone tools were made by humans. He was even a friend of Karl Marx in his later years and was one of the few people at Marx's funeral.

In the 1920s, Lankester worked to show that some Spiritualist mediums (people who claimed to talk to spirits) were fakes. He was also a popular science writer, sharing scientific ideas with the public through his weekly newspaper columns. These columns were later collected into books called Science from an Easy Chair.

Lectures

In 1903, he was invited to give the famous Royal Institution Christmas Lectures for young people. His topic was Extinct Animals.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ray Lankester para niños

In Spanish: Ray Lankester para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |