Invertebrate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Invertebrates

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

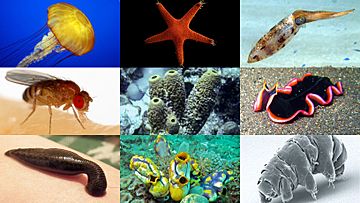

| Left to right: Chrysaora fuscescens (Cnidaria), Fromia indica (Echinodermata), Caribbean reef squid (Mollusca), Drosophila melanogaster (Arthropoda), Aplysina lacunosa (Porifera), Pseudobiceros hancockanus (Platyhelminthes), Hirudo medicinalis (Annelida), Polycarpa aurata (Tunicata), Milnesium tardigradum (Tardigrada). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Filozoa |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Groups included | |

|

|

Invertebrates are a huge group of animals that do not have a backbone or spinal column. This means they are all animals except for those in the chordate group called Vertebrata. You might know some invertebrates like arthropods (insects, spiders), mollusks (snails, squid), annelids (worms), echinoderms (starfish), and cnidarians (jellyfish).

Most animal species on Earth are invertebrates. Some experts believe that about 97% of all animal species are invertebrates! Many groups of invertebrates have more types of species than all vertebrates combined. Invertebrates come in all sizes, from tiny rotifers that are only 50 micrometers long (smaller than a grain of sand) to giant colossal squid that can be 9–10 meters (30–33 feet) long.

Some animals that are called invertebrates, like tunicates and lancelets, are actually more closely related to vertebrates than to other invertebrates. Because of this, the term "invertebrates" is not a true scientific grouping in taxonomy. It's more of a convenient way to talk about animals without backbones.

Contents

What does the word "invertebrate" mean?

The word "invertebrate" comes from Latin. The word vertebra means a joint, especially a joint in the spinal column. The root verto or vorto means "to turn." The prefix in- means "not" or "without." So, "invertebrate" simply means "without a backbone."

Why is "invertebrate" a special term?

The term invertebrates is not a precise scientific term like Arthropoda (arthropods) or Vertebrata (vertebrates). Those terms describe real scientific groups. "Invertebrata" is just a convenient word for animals that are not vertebrates. It doesn't describe a single, natural group of animals.

Even though it's not a formal scientific group, the idea of "invertebrates" has been used for over a hundred years. Scientists still use it as a simple way to refer to all animals that are not part of the Vertebrata group. Invertebrates do not have a skeleton made of bone, either inside or outside their bodies. They have many different body shapes. Many have soft, fluid-filled bodies, like jellyfish or worms. Others have hard outer shells, called exoskeletons, like insects and crustaceans.

Some of the most well-known invertebrate groups include sponges, cnidarians, flatworms, roundworms, segmented worms, echinoderms, mollusks, and arthropods. Arthropods include insects, crustaceans, and arachnids (spiders, scorpions).

How many invertebrate species are there?

The largest number of known invertebrate species are insects. The table below shows how many species have been described for some major invertebrate groups, according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species from 2014.3.

| Invertebrate group | Phylum | Image | Estimated number of described species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insects | Arthropoda |  |

1,000,000 |

| Arachnids | Arthropoda |  |

102,248 |

| Snails | Mollusca |  |

85,000 |

| Crustaceans | Arthropoda |  |

47,000 |

| Clams | Mollusca |  |

20,000 |

| Corals | Cnidaria |  |

2,175 |

| Octopuses/Squid | Mollusca |  |

900 |

| Velvet worms | Onychophora |  |

165 |

| Nautilus | Mollusca |  |

6 |

| Horseshoe crabs | Arthropoda |  |

4 |

| Others jellyfish, echinoderms, sponges, other worms etc. |

— | — | 68,658 |

| Total: | ~1,300,000 |

The IUCN estimates that about 66,178 vertebrate species have been described. This means that over 95% of all known animal species in the world are invertebrates!

What are the main characteristics of invertebrates?

The main thing all invertebrates have in common is that they do not have a backbone. This is the only trait that separates them from vertebrates. Like all animals, invertebrates are heterotrophs. This means they need to eat other organisms to get energy. Most invertebrates, except for sponges, have bodies made of different tissues. They also usually have a stomach or gut with one or two openings.

Body shape and symmetry

Most animals with many cells have some kind of symmetry. This can be radial (like a starfish), bilateral (like a human), or spherical (like a ball). However, some invertebrates have no symmetry at all. For example, all gastropods (snails and slugs) are asymmetrical. You can easily see this in snails with their spiral shells. Slugs look symmetrical on the outside, but their breathing hole is on the right side.

Other examples of asymmetry are fiddler crabs and hermit crabs. They often have one claw that is much bigger than the other. If a male fiddler crab loses its big claw, it will grow a new one on the opposite side after it molts. Animals that stay in one place, like sponges and coral colonies, are also asymmetrical.

Nervous system

The nerve cells (neurons) in invertebrates are different from those in mammals. Invertebrate cells react to things like injury, high temperatures, or changes in pH, just like mammals. The first neuron identified in an invertebrate was in the medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis.

Scientists have studied how sea hares (a type of mollusk) learn and remember using their pain-sensing neurons. Mollusk neurons can detect increasing pressure and tissue damage. Neurons have been found in many invertebrate species, including worms, mollusks, nematodes, and arthropods.

Respiratory system

One type of breathing system in invertebrates is the open respiratory system. This system is found in land arthropods like insects. It uses small openings called spiracles, tubes called tracheae, and even smaller tubes called tracheoles. These tubes carry gases like oxygen and carbon dioxide to and from the body's tissues.

The spiracles can be different in various insects. Generally, each body segment can have one pair of spiracles. These connect to a larger tracheal tube. The tracheae are like tiny tunnels that branch out all over the body, from very small to about 0.8 mm wide. The smallest tubes, tracheoles, go right into the cells. This is where diffusion of water, oxygen, and carbon dioxide happens.

Insects do not usually carry oxygen in their blood (called haemolymph), unlike vertebrates. Gas can move through this system by active breathing or just by passive diffusion. Many insects, like grasshoppers and bees, can actively pump air sacs in their abdomen to control airflow. In some water insects, the tracheae can exchange gas directly through the body wall, acting like a gill. Even though they are inside the body, the tracheae of arthropods are shed when the animal molts its exoskeleton.

Reproduction in invertebrates

Like vertebrates, most invertebrates reproduce through sexual reproduction. They create special cells called gametes. These are either small, moving sperm or larger, non-moving eggs. When sperm and egg join, they form a zygote, which grows into a new individual. Some invertebrates can also reproduce without a partner (asexually), or sometimes use both methods.

Scientists have learned a lot about meiosis (how reproductive cells are made) and reproduction by studying invertebrate species like the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) and the nematode worm (Caenorhabditis elegans). However, there is an amazing variety of ways invertebrates reproduce. For example, some oribatid mite species have reproduced asexually for over 400 million years!

Social interaction

Many invertebrates show social behavior. This includes cockroaches, termites, aphids, thrips, ants, bees, spiders, and more. Social interaction is especially clear in eusocial species, where animals live in highly organized groups, but it happens in other invertebrates too. Insects can recognize and use information shared by other insects.

Main invertebrate groups (Phyla)

The term invertebrates includes many different phyla (major animal groups). One of these groups is the sponges (Porifera). They were once thought to be very simple animals that branched off early from other animals. They don't have the complex organization seen in most other groups. Their cells are different, but usually not organized into clear tissues. Sponges typically eat by pulling water through their pores. Some scientists now think sponges might not be as primitive as once thought.

The ctenophores (comb jellies) and cnidarians (which include sea anemones, corals, and jellyfish) have radial symmetry. They have a digestive chamber with only one opening, which acts as both mouth and anus. Both groups have distinct tissues, but they are not organized into organs. They only have two main cell layers, so they are sometimes called diploblastic.

The echinoderms are also radially symmetrical and live only in the ocean. This group includes starfish, sea urchins, brittle stars, sea cucumbers, and feather stars.

The largest animal phylum is also found within invertebrates: the Arthropoda. This group includes insects, spiders, crabs, and their relatives. All arthropods have bodies divided into repeating segments, usually with paired legs or other parts. They also have a hard exoskeleton that they shed regularly as they grow. Two smaller groups, the Onychophora (velvet worms) and Tardigrada (tardigrades or water bears), are close relatives of arthropods and share some traits with them, but they don't have a hardened exoskeleton.

The Nematoda, or roundworms, are possibly the second largest animal phylum, and they are also invertebrates. Roundworms are usually microscopic and live in almost every environment where there is water. Many are important parasites. Smaller groups related to them are the Kinorhyncha, Priapulida, and Loricifera. These groups have a simpler body cavity. Other invertebrates include the Nemertea (ribbon worms) and the Sipuncula (peanut worms).

Another phylum is Platyhelminthes, the flatworms. These were once thought to be very simple, but it now seems they developed from more complex ancestors. Flatworms do not have a body cavity, just like their tiny relatives, the gastrotrichs. The Rotifera, or rotifers, are common in water environments. Invertebrates also include the Acanthocephala (spiny-headed worms), the Gnathostomulida, Micrognathozoa, and the Cycliophora.

Two very successful animal phyla are the Mollusca and Annelida. Mollusks are the second-largest animal phylum by number of species. They include animals like snails, clams, and squids. Annelids are segmented worms, such as earthworms and leeches. These two groups were once thought to be closely related because they both have a type of larva called a trochophore. Annelids were also thought to be closer to arthropods because they are both segmented. However, scientists now believe this segmentation developed separately in each group, due to many differences in their bodies and genes.

Some lesser-known invertebrate phyla include the Hemichordata (acorn worms) and the Chaetognatha (arrow worms). Other groups are Acoelomorpha, Brachiopoda, Bryozoa, Entoprocta, Phoronida, and Xenoturbellida.

How are invertebrates classified?

Invertebrates can be put into several main groups. Some of these groups are not used in formal scientific classification anymore, but they are still convenient terms. You can find more about each group at the links below.

- Sponges (Porifera)

- Comb jellies (Ctenophora)

- Medusozoans and corals (Cnidaria)

- Acoels (Xenacoelomorpha)

- Flatworms (Platyhelminthes)

- Bristleworms, earthworms and leeches (Annelida)

- Insects, springtails, crustaceans, myriapods, chelicerates (Arthropoda)

- Chitons, snails, slugs, bivalves, tusk shells, cephalopods (Mollusca)

- Roundworms or threadworms (Nematoda)

- Rotifers (Rotifera)

- Tardigrades (Tardigrada)

- Scalidophores (Scalidophora)

- Lophophorates (Lophophorata)

- Velvet worms (Onychophora)

- Arrow worms (Chaetognatha)

- Gordian worms or horsehair worms (Nematomorpha)

- Ribbon worms (Nemertea)

- Placozoa

- Loricifera

- Starfishes, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, sea lilies and brittle stars (Echinodermata)

- Acorn worms, cephalodiscids and graptolites (Hemichordata)

- Lancelets (Amphioxiformes)

- Salps, pyrosomes, doliolids, larvaceans and sea squirts (Tunicata)

History of invertebrates

The oldest animal fossils found seem to be from invertebrates. Fossils found in South Australia, about 665 million years old, might be early sponges. Some scientists think animals appeared even earlier, possibly a billion years ago, but they likely became multicellular later. Trace fossils (like tracks and burrows) from the late Neoproterozoic era show that there were worms, about 5 mm wide, that were as complex as earthworms.

Around 453 million years ago, animals started to become very diverse. Many important invertebrate groups developed at this time. Invertebrate fossils are found in different types of rock from the Phanerozoic eon. These fossils are often used to help date layers of rock.

How invertebrates were classified in the past

Carl Linnaeus first divided these animals into only two groups: Insecta and a group called Vermes (worms), which is no longer used. Later, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who worked at the National Museum of Natural History in France in 1793, created the term "invertebrate." He then split Linnaeus's two groups into ten. He separated Arachnida (spiders) and Crustacea (crabs) from Insecta. He also separated Mollusca (mollusks), Annelida (segmented worms), Cirripedia (barnacles), Radiata, Coelenterata, and Infusoria from Vermes. Today, invertebrates are classified into over 30 phyla, from simple animals like sea sponges and flatworms to complex ones like arthropods and mollusks.

Why is the "invertebrate" group still used?

The idea of "invertebrates" as animals without a backbone has led some to think of them as different from the "normal" animals (vertebrates). This might be because early researchers, like Lamarck, saw vertebrates as the "standard." In Lamarck's ideas about evolution, he thought that animals progressed toward a "higher form," and humans and vertebrates were closer to this ideal than invertebrates. Even though this idea of "goal-directed evolution" is no longer accepted, the division between invertebrates and vertebrates continues today.

Another reason this distinction remains is that Lamarck set a precedent with his classifications that is now hard to change. Also, some people might feel that vertebrates, including humans, deserve more attention. However, a zoology book from 1968 noted that dividing the animal kingdom into vertebrates and invertebrates is "artificial" and shows a human bias. The book also points out that this group combines a huge number of species, so no single trait describes all invertebrates. Plus, some species called invertebrates are actually more closely related to vertebrates than to other invertebrates.

Invertebrates in scientific research

For many centuries, biologists didn't pay much attention to invertebrates. They focused more on large vertebrates or animals that were useful or popular. The study of invertebrate biology didn't become a major field until the work of Linnaeus and Lamarck in the 18th century. In the 20th century, invertebrate zoology became a very important area of natural science. It led to big discoveries in medicine, genetics, paleontology (study of fossils), and ecology. Studying invertebrates has even helped law enforcement, as arthropods, especially insects, can provide information for crime scene investigators.

Two of the most studied animals in science today are invertebrates: the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) and the nematode worm (Caenorhabditis elegans). They have been studied very closely and were among the first living things to have their entire genetic code (genome) sequenced. This was easier because their genomes are smaller. Scientists also study invertebrates in aquatic biomonitoring to see how water pollution and climate change affect the environment.

See also

In Spanish: Invertebrado para niños

In Spanish: Invertebrado para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |