Raphael Weldon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

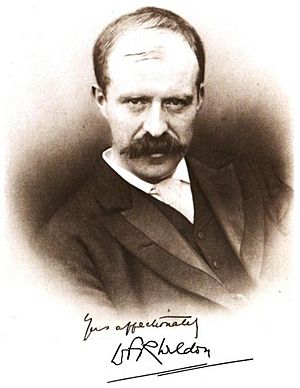

Walter Frank Raphael Weldon

|

|

|---|---|

Raphael Weldon

|

|

| Born | 15 March 1860 London, England

|

| Died | 13 April 1906 (aged 46) Oxford, England

|

| Alma mater | St John's College, Cambridge |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Zoology, biometry |

| Institutions | St John's College, Cambridge University College London Oxford University |

| Academic advisors | Francis Maitland Balfour |

| Influences | Francis Galton, Karl Pearson |

Walter Frank Raphael Weldon (born March 15, 1860 – died April 13, 1906) was an English scientist. He was an evolutionary biologist, which means he studied how living things change over many generations. He also helped start a field called biometry, which uses math and statistics to study biology. Weldon was one of the first editors of a science magazine called Biometrika, working with Francis Galton and Karl Pearson.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Walter Weldon was the second child of Walter Weldon and Anne Cotton. His father was a journalist and chemist. In 1883, Walter Weldon married Florence Tebb. Her father, William Tebb, worked to make society better.

Weldon first planned to become a doctor. He studied at University College London in 1876-1877. There, he learned from the zoologist E. Ray Lankester and the mathematician Olaus Henrici. The next year, he moved to King's College London and then to St John's College, Cambridge in 1878.

At Cambridge, Weldon studied with Francis Maitland Balfour, a scientist who studied how living things develop. Balfour greatly influenced Weldon, and he decided to focus on science instead of medicine. In 1881, he earned a top degree in Natural Science. After that, he went to the Naples Zoological Station to study marine animals. He died in 1906 from a lung illness and is buried in Oxford.

A Career in Zoology

When Weldon returned to Cambridge in 1882, he became a university lecturer. He taught about Invertebrate Morphology, which is the study of how animals without backbones are shaped. Weldon focused on understanding marine life and why some of these animals died more often than others.

In 1889, Weldon took over from E. Ray Lankester as the head of Zoology at University College London. He also became the curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology. In 1890, he was chosen to be a member of the Royal Society, a famous group of scientists. Many important zoologists supported his election, including Thomas Henry Huxley and Edward Bagnall Poulton.

The Birth of Biometry

Weldon's interests began to shift from studying animal shapes to looking at how living things vary and how different traits are connected. He started using statistical methods developed by Francis Galton. Weldon believed that understanding how animals change over time was "essentially a statistical problem."

He began working with Karl Pearson, a mathematician at University College. Their partnership was very important. Pearson laid the groundwork for modern statistics during their time together. Even when Weldon moved to Oxford University in 1899, their collaboration continued.

Weldon was one of the first scientists to show how natural selection works in wild animal groups. He showed how it could keep traits stable or make them change in a certain direction.

In 1893, a Royal Society group was formed with Weldon, Galton, and Pearson. Their goal was to use statistics to study how organisms vary. In 1894, Weldon wrote that the questions about evolution were "purely statistical." He felt that using statistics was the only way to test the idea of evolution.

The Mendel vs. Biometry Debate

Around 1900, the work of Gregor Mendel on genetics was rediscovered. This led to a big disagreement between Weldon and Pearson on one side, and William Bateson on the other. Bateson, who had been taught by Weldon, strongly disagreed with the biometricians.

This argument was about how evolution works and whether statistical methods were useful. The debate became less intense after Weldon died in 1906. However, the general discussion between those who favored statistics (biometricians) and those who favored genetics (Mendelians) continued. It wasn't until the 1930s that these ideas were combined into what is now called the modern evolutionary synthesis.

After Weldon's death, Oxford University created the Weldon Memorial Prize in his honor. It is given out every year.

Weldon's Dice Experiment

In 1894, Weldon did an interesting experiment. He rolled 12 dice 26,306 times! He collected all this data to see if the differences he observed in his results were just due to chance. Karl Pearson later used Weldon's dice data in his important work on the chi-squared statistic, which helps scientists understand if their results are meaningful or just random.

Images for kids

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |