Edward Bagnall Poulton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

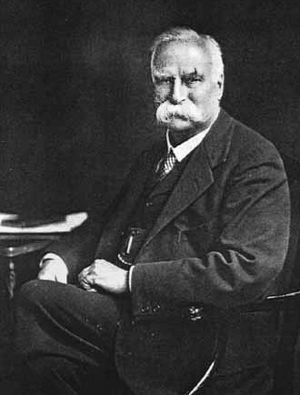

Sir Edward Bagnall Poulton

|

|

|---|---|

Sir Edward Bagnall Poulton

Photograph by James Lafayette |

|

| Born | 27 January 1856 |

| Died | 20 November 1943 (aged 87) |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Jesus College, Oxford |

| Known for | Aposematism, frequency-dependent selection, camouflage |

| Awards | Linnean Medal (1922) Hope Professor of Zoology |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Evolutionary biology |

| Institutions | University of Oxford |

| Influences | Charles Darwin, August Weismann, Alfred Russel Wallace |

Sir Edward Bagnall Poulton (born January 27, 1856 – died November 20, 1943) was an important British scientist. He studied how living things change over time, a field called evolutionary biology. Poulton strongly believed in natural selection, which is how nature chooses the best traits for survival. Many scientists at the time, like Reginald Punnett, doubted this idea.

Poulton came up with the word "sympatric" to describe how new species can evolve in the same place. In his book The Colours of Animals (1890), he was the first to explain "frequency-dependent selection". This is when the success of a trait depends on how common it is.

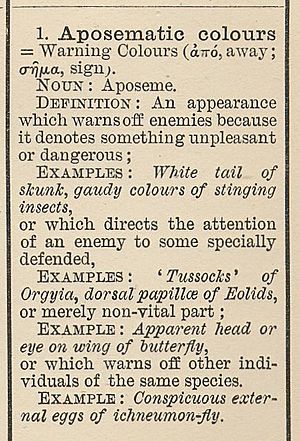

He is also famous for his groundbreaking work on animal coloration. Poulton invented the term "aposematism" for warning colors. These are bright colors that tell predators an animal is dangerous or tastes bad. He also did experiments on "protective coloration," which is another name for camouflage. Poulton became the Hope Professor of Zoology at the University of Oxford in 1893.

Contents

About Edward Poulton's Early Life

Edward Poulton was born in Reading, Berkshire, England, on January 27, 1856. His father, William Ford Poulton, was an architect. Edward went to Oakley House School in Reading.

From 1873 to 1876, Poulton studied at Jesus College, Oxford. His teachers included George Rolleston and John Obadiah Westwood. Westwood was an entomologist, a scientist who studies insects, but he did not agree with Charles Darwin's ideas. Poulton earned a top degree in natural science.

He stayed connected with Jesus College for 70 years. He was a student, a teacher, and later a Fellow (a senior member of the college). Poulton was very generous to the college.

King George V made him a knight in 1935, so he became "Sir" Edward Poulton. He passed away in Oxford on November 20, 1943.

Poulton's Scientific Career

Throughout his career, Poulton was a strong supporter of Charles Darwin's ideas. He believed that natural selection was the main force driving evolution. He not only admired Darwin but also defended August Weismann, who was a key figure in "neo-Darwinism." This idea focused on genes being passed down.

Poulton helped translate Weismann's work into English. He supported Weismann's idea that germ-plasm (the material that carries genetic information) is passed on unchanged. Poulton noted that new research showed that traits gained during an animal's life (called Lamarckism) likely did not play a role in how species form.

His 1890 book, The Colours of Animals, introduced important ideas. These included frequency-dependent selection and aposematic coloration. The book also supported Darwin's theories of natural selection and sexual selection, which were not very popular at the time.

Poulton did many experiments on the colors of caterpillars. He wanted to see if their food, background, or other things affected their color changes. He found that caterpillars could sense background colors even when they were blind. This was one of the first times scientists suggested that animals could "see" without their eyes.

Poulton also greatly expanded the Hope entomological collections. These are collections of insects at Oxford University. He collected so many specimens that he earned the nickname "Bag-all" Poulton. Many of his specimens are still kept in biscuit tins today.

In his 1896 book, Charles Darwin and the Theory of Natural Selection, Poulton called Darwin's Origin of Species the "greatest work" in biology. He felt that critics of natural selection had not truly understood it. This view is much more common today than it was then. At that time, scientists did not fully understand inheritance, which made it hard to grasp how evolution worked.

In 1897, Poulton talked to members of the Royal Entomological Society of London. He found that many doubted that mimicry (when one species looks like another) came from natural selection. Only three people fully supported Batesian mimicry and Müllerian mimicry. Others doubted if the "model" animals were truly inedible. Some even tasted them! Many scientists still preferred other ideas over natural selection.

Genetics and Evolution

The rediscovery of Gregor Mendel's work on genetics filled a big gap in evolution theory. However, at first, many thought it went against natural selection. There was a long debate between Poulton and Reginald Punnett. Punnett was a follower of William Bateson and the first Professor of Genetics at Oxford.

Punnett's 1915 book, Mimicry in Butterflies, argued against selection as the main cause of mimicry. He pointed out several things:

- He noted that there were no transitional forms (steps between species). Also, male butterflies often did not mimic other species. Selection theory did not explain this.

- He wondered about "polymorphic mimicry." This is when one butterfly species mimics several different models. Breeding experiments showed these different forms separated cleanly, following Mendel's laws.

- He felt there was little proof that birds were strong forces of selection. Not much was known about how well birds could tell things apart.

- He believed that tiny changes building up over time did not fit with how traits were inherited.

Punnett thought mimicry came from sudden, big changes called saltations (mutations). He thought natural selection might only help keep a mimic once it had formed.

However, over time, each of Punnett's points was disproven. Field observations and experiments showed that birds often did act as selective agents for insects. Evidence for small mutations being common appeared when experiments were designed to find them. Scientists like E.B. Ford and Theodosius Dobzhansky explained polymorphism. They developed ways to study animal populations in their natural homes.

The ideas from field observations and experimental genetics slowly came together. This led to the "modern synthesis" in the mid-1900s. It is now widely accepted that mutations create new variations in a population. Natural selection then describes how some of these variations help animals survive better. Poulton's ideas were much closer to our modern understanding of evolution.

In 1937, at age 81, Poulton gave a speech to the British Association. He talked about the history of evolutionary thought. He said the work of J.B.S. Haldane, R.A. Fisher, and Julian Huxley was vital. Their work showed how Mendel's genetics and natural selection were connected. Poulton said that many biologists' observations and experiments had "greatly strengthened" the research on mimicry and warning colors. This research was started by pioneers like Bates, Wallace, Meldola, Trimen, and Müller.

Poulton's Family Life

Poulton lived with his family at 56 Banbury Road in North Oxford. This was a large Victorian house built in 1866.

In 1881, he married Emily Palmer. Her father, George Palmer, was a Member of Parliament and head of the Huntley and Palmer biscuit company. Edward and Emily had five children. Sadly, three of their children passed away by 1919. Their oldest son, Dr. Edward Palmer Poulton, died in 1939. This meant that only his daughter Margaret Lucy (1887–1965) lived longer than Sir Edward. Margaret married Dr. Maxwell Garnett. Poulton's son, Ronald Poulton-Palmer, played international rugby for England. He died in May 1915 during World War I. His first daughter, Hilda, married Dr. Ernest Ainsley-Walker and died in 1917. His youngest daughter, Janet Palmer, married Charles Symonds in 1915 and died in 1919.

Poulton's Legacy

Poulton is remembered as one of the first to think about the biological species concept. This idea defines a species as a group of organisms that can reproduce with each other.

According to Ernst Mayr, Poulton created the term "sympatric" for species. He also invented the word "aposematism" for warning coloration.

Poulton, along with scientists like Julian Huxley, J.B.S. Haldane, R.A. Fisher, and E.B. Ford, helped promote the idea of natural selection. They did this during many years when it was not widely accepted.

G.D. Hale Carpenter took over Poulton's role as Hope Professor of Entomology at Oxford University from 1933 to 1948.

Poulton's Published Works

Poulton wrote over 200 scientific papers and books during his sixty-year career.

- 1890. The Colours of Animals: Their Meaning and Use, Especially Considered in the Case of Insects.

- 1896. Charles Darwin and the Theory of Natural Selection.

- 1904. What is a Species? (A speech he gave to the Entomological Society of London).

- 1908. Essays on Evolution.

- 1909. Charles Darwin and the Origin of species; addresses, etc., in America and England in the year of the two anniversaries.

- 1915. Science and the Great War: The Romanes Lecture for 1915.

Awards and Honours

- He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in June 1889.

- He was President of the Linnean Society from 1912 to 1916.

- He received the Royal Society's Darwin Medal in 1914.

- He was awarded the Linnean Society's Linnean Medal in 1922.

- He was made a Knight in 1935.

- He was President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1937.

See also

- Adaptive Coloration in Animals (a book by Hugh Cott)

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |