Henry Walter Bates facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Walter Bates

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 8 February 1825 |

| Died | 16 February 1892 (aged 67) |

| Resting place | East Finchley Cemetery, London |

| Known for | Amazon voyage Batesian mimicry |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Ann Mason |

| Awards | President of the Entomological Society of London, fellow of the Linnaean Society, and of the Royal Society |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mimicry, natural history, geography |

| Institutions | Royal Geographical Society, London |

| Influences | Alfred Russel Wallace (and others) |

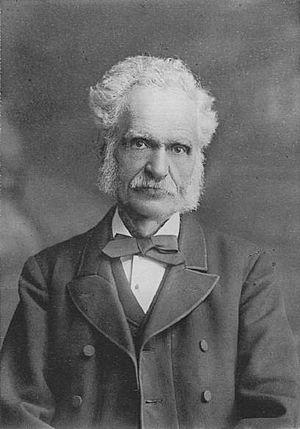

Henry Walter Bates FRS FLS FGS (born February 8, 1825, in Leicester – died February 16, 1892, in London) was an English naturalist and explorer. He was the first scientist to describe mimicry in animals.

Bates is most famous for his trip to the rainforests of the Amazon. He went with Alfred Russel Wallace in 1848. Wallace returned in 1852, but sadly lost his collection when his ship caught fire. Bates stayed for eleven years, returning in 1859. He sent back over 14,712 species, mostly insects. About 8,000 of these were new to science! Bates wrote about his amazing discoveries in his well-known book, The Naturalist on the River Amazons.

Contents

Early Life and Inspiration

Bates grew up in Leicester in a family that loved to read. Like many famous scientists, he had a basic education until he was about 13. Then, he started working for a hosiery maker.

In his free time, Bates studied and collected insects in Charnwood Forest. He even had a short paper about beetles published in a science journal in 1843.

Bates became good friends with Alfred Russel Wallace, who was also interested in insects. They both read many books about nature and the world. These books included ideas about how populations grow and how Earth's geology changes. They also read about Charles Darwin's voyage on the The Voyage of the Beagle. A book called Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation made them think about how living things change over time.

They also read about an expedition up the Amazon River. This made them dream of their own adventure. They hoped it would help them start their careers as naturalists.

The Great Amazon Adventure

In 1847, Wallace and Bates decided to go on an expedition to the Amazon rainforest. Their plan was to pay for their trip by sending animal and plant specimens back to London. An agent there would sell them.

The two friends were already skilled at studying insects. They met in London to get ready. They looked at South American plants and animals in big collections. They also made lists of what museums and collectors wanted. You can find letters between Wallace and Bates online at Wallace Letters Online.

Bates and Wallace sailed from Liverpool in April 1848. They arrived in Pará (now Belém) in May. For their first year, they lived near the city, collecting birds and insects. After that, they decided to explore separately.

Bates traveled up the Amazon River. He went to places like Óbidos, Manaus, and the Upper Amazon. Tefé became his main base for four and a half years. His health eventually got worse, and he returned to Britain in 1859. He had spent almost eleven years in the Amazon!

To avoid losing his collection like Wallace did, Bates sent his specimens on three different ships. He then spent the next three years writing his book, The Naturalist on the River Amazons. It is known as one of the best books about natural history travels.

Life After the Amazon

In 1863, Bates married Sarah Ann Mason. From 1864, he worked as an assistant secretary for the Royal Geographical Society. He sold his butterfly collection and started focusing on beetles.

Bates was also the president of the Entomological Society of London for a few years. In 1871, he became a member of the Linnaean Society. In 1881, he was chosen as a member of the important Royal Society.

He passed away in 1892. A large part of his collections are now in the Natural History Museum. Bates was often asked to help identify difficult insect specimens.

Alfred Russel Wallace wrote about Bates after his death. He called Bates's 1861 paper on mimicry in butterflies "remarkable and epoch-making." Wallace praised Bates's work in entomology (the study of insects).

Bates's Discoveries

Henry Bates was one of several great naturalists who supported the idea of evolution by natural selection. This idea was developed by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace.

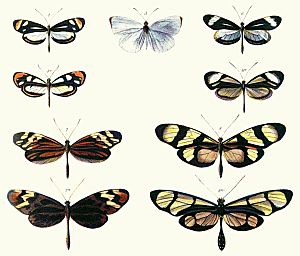

Bates studied butterflies in the Amazon. His work led him to explain mimicry for the first time. The type of mimicry named after him is called Batesian mimicry. This is when a harmless animal looks like a harmful or bad-tasting animal.

For example, some hover-flies look like wasps or bees. Hover-flies don't sting, but their colors warn predators to stay away. This helps the hover-fly survive because predators avoid what looks like a stinging insect. The mimicry doesn't have to be perfect to help the harmless animal.

Bates noticed that some butterflies, called Heliconids, were:

- Common and easy to spot.

- Slow-flying.

- Found in groups.

- Adults visited flowers often.

- Their young (larvae) fed together.

Bates saw that many Heliconid species had other species (Pierids) that looked just like them. It was hard to tell them apart when they were flying! These mimic butterflies flew in the same parts of the forest as the Heliconids. They often flew together.

Bates thought that predators learned to avoid the bad-tasting Heliconids. Because the harmless species looked like the Heliconids, they also gained some protection. This idea about warning signals and mimicry helped create the study of evolutionary ecology.

Bates, Wallace, and another scientist named Fritz Müller believed that Batesian mimicry and Müllerian mimicry showed how natural selection works. This idea is now a standard part of biology. Scientists still study these ideas today. They connect to how new species form, genetics, and how living things develop.

Life in Ega

Bates spent almost a year in a place called Ega (now Tefé) in the Upper Amazon. He wrote that people there ate turtle regularly. He also found many insects. He discovered over 7,000 species of insects in the area, including 550 different kinds of butterflies.

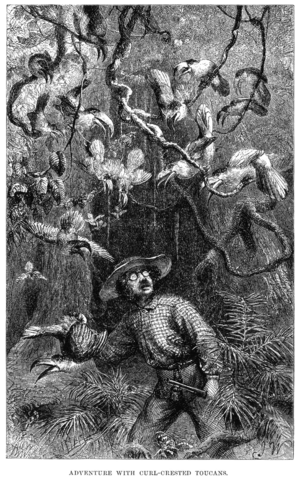

Bates even nursed a sick toucan back to health. He named the toucan Tocáno, after its calls. Tocáno was smart and fun. He loved to eat! He mainly ate fruit but learned meal times perfectly. He would also eat meat and fish.

Butterfly Classification

Bates did his original work on a group of noticeable butterflies he called Heliconidae. He divided them into two groups. One group, the Danaoid Heliconids, are now called Ithomiini. They are related to milkweed butterflies. The other group, the Acraeoid Heliconids, are now called tribe Heliconiini, or longwings.

Both groups belong to the family Nymphalidae. Both tend to eat poisonous plants. Milkweed plants give poisonous chemicals to milkweed butterflies, making both the caterpillar and adult bad-tasting. Ithomiines get their toxins from the nectar they drink as adults. Heliconiine caterpillars eat poisonous Passiflora vines.

Legacy

Henry Walter Bates is remembered in the scientific name of a South American snake, Corallus batesii. His theory of mimicry is also named after him: Batesian mimicry.

See also

In Spanish: Henry Walter Bates para niños

In Spanish: Henry Walter Bates para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |