Cesare Lombroso facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

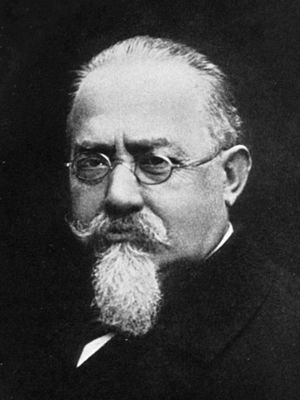

Cesare Lombroso

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Ezechia Marco Lombroso

6 November 1835 Verona, Lombardy–Venetia

|

| Died | 19 October 1909 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Italian school of positivist criminology |

| Children | Gina Lombroso |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Influences | |

| Influenced |

|

| Signature | |

Cesare Lombroso was an Italian doctor and professor who lived from 1835 to 1909. He is famous for his ideas about crime and criminals. Lombroso believed that people were "born criminals" and that you could tell if someone was a criminal by certain physical features. He thought these features were like signs from an earlier stage of human development. His ideas helped start the "Italian school of criminology," which is the study of crime.

Contents

Early Life and Studies

Cesare Lombroso was born in Verona, Italy, on November 6, 1835. His family was wealthy and Jewish. His father, Aronne Lombroso, was a tradesman, and his mother was Zeffora Levi. Because his family had many rabbis, Lombroso studied many different subjects at university.

He went to universities in Padua, Vienna, and Paris. He studied literature, languages, and old history. Even with these studies, he decided to become a doctor. He earned his medical degree from the University of Pavia.

His Career and Ideas

Lombroso started his career as an army surgeon in 1859. Later, in 1866, he became a lecturer at the University of Pavia. In 1871, he took charge of a mental hospital in Pesaro.

In 1878, he became a professor at the University of Turin. He taught about forensic medicine, which is how medicine is used in legal cases. That same year, he wrote his most important book, L'uomo delinquente (which means The Criminal Man). This book became very famous and was translated into many languages.

Lombroso's main idea was that criminal behavior was inherited, like a trait passed down in a family. He thought that criminals had certain physical signs, such as unusual skull shapes or facial features. He believed these signs showed that criminals were less developed, like people from ancient times.

He later became a professor of psychiatry in 1896 and then of criminal anthropology in 1906 at Turin University.

Personal Life and Later Years

Cesare Lombroso married Nina de Benedetti on April 10, 1870. They had five children. One of their daughters, Gina Lombroso, later wrote a summary of her father's work.

Later in his life, Lombroso's ideas changed a bit. His son-in-law, Guglielmo Ferrero, influenced him. Lombroso started to believe that social factors, not just inborn traits, could also play a part in why someone became a criminal.

He passed away in Turin in 1909.

Lombroso's Impact

Lombroso is often said to have created the word "criminology," which is the scientific study of crime. He also helped make the study of psychiatry a recognized field in universities.

His ideas were part of what was called the "positivist school" of criminology. This school believed that criminal behavior was caused by things you could measure, like physical traits, rather than just being a choice. This was different from earlier ideas that said people chose to commit crimes.

Lombroso thought that a person's chances of having a mental illness could be seen in their appearance. For example, he looked for links between tattoos and certain behaviors. He also believed that being left-handed was connected to criminal behavior, which was a common belief at the time.

His work also changed how criminals were treated. Sometimes, the punishment for a crime would depend on the defendant's physical appearance, based on Lombroso's theories.

Lombroso is also known for helping to create places called "criminal insane asylums." These were hospitals where people who committed crimes and had mental illnesses could get treatment. Before this, they might have just been put in regular jails. Places like Bridgewater State Hospital in the United States are examples of such institutions.

Genius and Madness

Lombroso also wrote a book called Genio e Follia (Genius and Madness). In this book, he explored the idea that genius was a special kind of mental illness. He believed that brilliant people and people with mental illnesses shared some of the same roots.

He tried to prove this by looking for "degenerate symptoms" in famous geniuses like William Shakespeare and Plato. He even wanted to examine the famous writer Leo Tolstoy to see if he had these signs. However, their meeting did not go well, and Tolstoy later showed his dislike for Lombroso's methods in his novel Resurrection.

Lombroso collected a lot of "psychiatric art" to support his ideas. He thought he could find common features in the art made by people with mental illnesses. While his specific ideas are not used today, his work inspired later studies on art and mental health.

Later Interests

Towards the end of his life, Lombroso became interested in spiritualism, which is the belief in spirits and communication with them. Even though he was an atheist, he started to believe in the existence of spirits. He wrote a book called After Death – What? where he talked about his views on the paranormal. He even thought that a medium named Eusapia Palladino was truly able to communicate with spirits. However, many other scientists thought she was a fraud.

Lombroso also studied a disease called pellagra, which was common in rural Italy. He believed it was caused by a lack of proper food, which was later proven to be true. This disease, like cretinism (which he studied early in his career), was often linked to poverty.

Before he died, the Italian government passed a law in 1904. This law set rules for how mental hospitals should treat patients and how mentally ill criminals should be admitted. This law gave doctors more power in deciding how to treat people with mental illnesses who had committed crimes.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Cesare Lombroso para niños

In Spanish: Cesare Lombroso para niños