Jeanne Villepreux-Power facts for kids

Jeanne Villepreux-Power (born Jeanne Villepreux on September 24, 1794 – died January 25, 1871) was a remarkable French scientist. She is known as a pioneer in marine biology, the study of ocean life. The English biologist Richard Owen even called her the "Mother of Aquariophily."

In 1832, Jeanne invented and built the very first aquariums. These special glass tanks allowed her to study aquatic animals up close. Her method of using aquariums to observe marine life is still used by scientists today. She was also a leading researcher on cephalopods, a group of animals that includes octopuses and squids. She famously proved that the Argonauta argo (also called the paper nautilus) creates its own shell, rather than finding one like a hermit crab. Besides her science, Villepreux-Power was a talented dressmaker, an author, and someone who cared deeply about protecting nature. In 1832, she became the first female member of the Accademia Gioenia di Catania, a scientific academy.

Contents

Early Life and Big Dreams

Jeanne Villepreux-Power was born in Juillac, Corrèze, France. Her birthday was either September 24 or 25, 1794. She was the oldest child of a shoemaker and a seamstress. Jeanne grew up in the countryside and learned to read and write. Her family lived simply, and her mother passed away when Jeanne was eleven.

A New Life in Paris and Sicily

In 1812, at age 18, Jeanne made a long journey to Paris. She walked over 400 kilometers to become a dressmaker. During her trip, she faced a difficult situation and lost her important travel documents. She had to get new papers before continuing.

This delay meant she missed her first job opportunity. However, she soon found work as a seamstress assistant. Jeanne worked hard and became very skilled. By 1816, she was famous for designing the wedding dress of Princess Caroline.

In 1818, she met and married James Power, an English merchant. She then took the name Villepreux-Power. The couple moved to Sicily, an island in Italy, and lived in Messina for about 25 years.

Exploring the World of Science

After moving to Sicily, Jeanne became very interested in learning more. She began to study geology (the study of Earth), archeology (the study of ancient cultures), and natural history. She especially loved observing and experimenting with animals, both on land and in the sea.

Jeanne wanted to understand all the plants and animals on the island. She explored Sicily, carefully noting its flora and fauna (plants and animals). She collected samples of minerals, fossils, butterflies, and shells. She wrote down her discoveries in books like Itinerario della Sicilia and Guida per la Sicilia.

Inventing the Aquarium

Jeanne then focused on cephalopods and other marine creatures. She realized it was hard to study sea animals over time. Land animals were easier to watch, but marine life was hidden underwater. To solve this, she invented a special glass container.

She developed three types of these containers to study live marine life. The first was the glass aquarium we know today. The second was a glass container inside a case that could be lowered into the ocean. The third was a large cage, anchored at sea, for bigger marine animals like molluscs. This was a huge step forward! She was the first to record that some octopuses could use tools to open the shells of their prey.

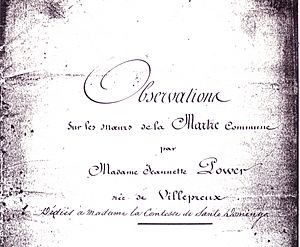

In 1834, a professor named Carmelo Maravigna praised Jeanne's invention. He wrote that she deserved credit for creating the aquarium and using it to study sea life. Her first book, published in 1839, described her experiments. It was called Observations et expériences physiques sur plusieurs animaux marins et terrestres.

Her second book, Guida per la Sicilia, came out in 1842. It has been republished by the Historical Society of Messina. She also studied molluscs and their fossils. She was especially fascinated by the Argonauta argo, also known as the paper nautilus.

At that time, scientists weren't sure if the Argonaut made its own shell. Some thought it might find and use a shell from another animal, like a hermit crab. Jeanne's careful work proved that Argonauts do indeed grow their own beautiful shells. This was a groundbreaking discovery, though she faced some disagreement for her findings.

Protecting Ocean Life

Jeanne Villepreux-Power also cared about conservation. She helped develop ideas for sustainable aquaculture in Sicily. Aquaculture is like farming fish and other sea animals. She was one of the first to explore how aquaculture could help protect and bring back fish populations. She thought about using cages near the shore to raise fish at different stages of their lives. These fish could then be moved to rivers where populations were low.

Her important work earned her recognition. She became the first woman member of the Accademia Gioenia di Catania. She was also a correspondent member of the London Zoological Society and many other scientific groups.

Amazing Innovations and Lasting Impact

Jeanne Villepreux-Power greatly advanced marine biological research. She joined important scientific societies because of her incredible invention. Her innovation solved a big problem: how to see underwater clearly. Her solution, the first-ever glass aquarium, completely changed how scientists studied marine life.

Before her invention, studying sea creatures was very difficult. It was hard to observe them in their natural homes. This made it tough for marine biology to grow as a science. Jeanne's idea fixed this problem. It helped scientists learn so much more about how marine animals live and behave. She created different aquarium models. Some were for shallow waters, and others were cage-like designs that could be lowered deep into the ocean. This expanded what marine biologists could study. For her outstanding work, Villepreux-Power became the first female member of the Catania Accademia and many other science academies.

Jeanne Villepreux-Power’s invention is still used today. While aquariums have improved over time, her core idea lives on. There are now more than 200 marine aquariums and ocean life centers around the world. Aquariums are popular places for both kids and adults to learn about sea creatures. We wouldn't be able to study aquatic life so easily without her innovation. The modern style of the glass aquarium was further developed by British biologist Philip Gosse (1810–1888). The first public aquarium opened in London in 1853, and Gosse provided the displays. Aquariums quickly became popular with many people. After London, the Berlin Aquarium Unter den Linden opened in 1869, and the Public Aquarium of Trocadero in Paris opened in 1867.

Later Years and Legacy

In Jeanne's time, women were not allowed to give talks at scientific conferences or work in universities. So, her discoveries were shared around the world with the help of others. Sir Richard Owen, a leading British scientist, presented her research to the London Zoological Society. They had communicated throughout her experiments. Her findings were quickly published in German, French, and English, spreading across Europe.

Jeanne Villepreux-Power and her husband left Sicily in 1843. Sadly, many of her research notes and scientific drawings were lost in a shipwreck. Even though she continued to write, she did not conduct new research. However, she became a public speaker. She and her husband divided their time between Paris and London. During a difficult time in Paris in the winter of 1870, she returned to her hometown of Juillac. She passed away in January 1871.

Remembering Jeanne Villepreux-Power

It took many years for Jeanne Villepreux-Power's amazing work to be fully recognized again. In 1997, her contributions were rediscovered after being largely forgotten for over a century. That same year, a crater on the planet Venus was named "Villepreux-Power" in her honor. It was discovered by the Magellan probe.

In 2026, Jeanne Villepreux-Power was announced as one of 72 historical women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics). Their names were proposed to be added to the 72 men already celebrated on the Eiffel Tower in Paris. This plan was announced by the Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo. It followed recommendations from a committee led by Isabelle Vauglin and Jean-François Martins.

See also

In Spanish: Jeanne Villepreux-Power para niños

In Spanish: Jeanne Villepreux-Power para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |