Jerez uprising facts for kids

The Jerez uprising was a short rebellion by farmers in Jerez, Spain, in 1892. About 500 to 600 farmworkers marched into the town with their tools. They wanted prisoners to be set free and better economic conditions for everyone. The uprising was stopped within hours, and three people died. Even though the event was small, the government's very harsh response led to many protests and even bombings later on.

After the uprising, 315 farmworkers, anarchists, and labor organizers were arrested. The authorities focused on stopping anarchism in the area. Anarchism is a political idea that believes in no government or rulers. Historians still discuss how much anarchism was truly involved in this specific uprising.

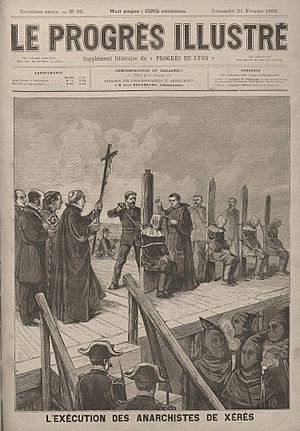

Many trials were held by military courts. Of 54 people on trial, four were executed. Fourteen others were sentenced to life in prison, and seven received shorter sentences. Newspapers that supported freedom and independent ideas said the government's response was too harsh. They felt it didn't help the desperate people who started the uprising. Anarchist newspapers, which were also targeted by the government, warned of revenge. After the executions, protests happened across Spain and at Spanish offices in Europe. Bombings also occurred. Later, in 1893, an anarchist named Paulí Pallàs tried to assassinate a military general involved in the repression. This led to more bombings throughout the 1890s.

Why the Uprising Happened

The rural region of Andalusia in Spain had a long history of peasant rebellions. These revolts started in the 1850s and continued into the 20th century. By 1870, some of these revolts began to be linked with the anarchist movement. They were connected to the Spanish Chapter of the First International, a group that aimed to unite workers worldwide. However, experts still debate how strongly anarchism caused these rural rebellions.

What Happened During the Uprising

On the night of January 8, 1892, about 500 to 600 farmworkers, known as campesinos, entered Jerez. They carried their farm tools. They hoped to start a rebellion. The uprising didn't have one single cause. Their main demands were the release of prisoners and improvements to the local economy.

The uprising was quickly stopped within hours. The townspeople did not support the farmworkers, and the military stepped in. Three people were killed: a tax official, a wine salesman, and a soldier. The tax official and wine salesman were attacked because they were seen as wealthy. The soldier was shot by mistake.

Historians have long discussed how much anarchism was connected to the Jerez uprising. Some of the farmworkers were anarchists, but not all of them. The group had clear demands about their living conditions. They were not just trying to cause destruction. One historian, James Michael Yeoman, noted that the desire for revolution was a factor, but so was the rain that night, which kept many potential participants at home. While the violence that followed is linked to anarchism, the ideas of anarchism don't fully explain everything that happened.

What Happened After

The government's response to the uprising was extremely harsh, even though the uprising itself was not very big. The labor movement in the Cádiz province was forced to go underground. Their organizations were closed, their newspapers stopped publishing, and their activists were arrested.

Local authorities immediately blamed the uprising on the anarchist movement. The army was ordered to bring back order. They strongly put down what they saw as a military revolt. The Spanish Civil Guard spent months arresting anarchists and labor activists from the countryside. They especially targeted people who wrote and shared anarchist newspapers. They believed these papers were key to spreading ideas of revolt among workers. In court, simply having issues of anarchist newspapers was seen as proof of guilt. In total, 315 people were arrested during this time. Most of them were farmworkers who identified as anarchists.

The government's crackdown was so fast that anarchist newspapers struggled to report on the uprising. Anarchists often had to rely on official and mainstream news reports. Some anarchist papers described the uprising as revolutionary violence. They called it a natural reaction to the extreme poverty in the region. The Seville anarchist paper La Tribuna Libre was shut down after it supported future revolutionary actions.

More often, anarchist papers denied that the uprising was fully anarchist, but they didn't condemn it. Le Corsair from A Coruña said the farmworkers' anger was caused by unfair treatment from farm owners. It also mentioned the 1882 Mano Negra affair, another controversial event. This paper criticized the "bourgeois press" (newspapers for the wealthy) for using the uprising to make anarchism look bad. La Anarquía, the largest Spanish anarchist newspaper outside of Catalonia, doubted the uprising's potential for revolution. It felt the uprising was not organized enough to be a true political or social revolution. All anarchist papers denied the mainstream claim that anarchists had started the uprising. They did this either to avoid censorship or because anarchists believed their revolutions would not have leaders, only ideas spread through propaganda.

The first trials began a month after the uprising, in February. These were military trials for serious charges. The main evidence came from an informant and statements taken under pressure. Of the eight people on trial, four were executed on February 10, 1892. They were Antonio Zarzuela and Jesús Fernández Lamela, who said they were anarchists and were accused of starting the uprising. Manuel Fernández Reina and Manuel Silva Leal were executed for a murder. Four others received life sentences. One of them died in his cell on the day of the executions. Two denied being anarchists, and the fourth was the informant. Another trial later in 1892 involved 46 people. Ten received life sentences, and seven received sentences between 8 and 20 years. Two people accused of planning the uprising with Fermín Salvochea (who was in prison at the time) received life sentences. Salvochea himself received a 12-year sentence.

Independent and liberal newspapers criticized how severe the government's response was. El Heraldo de Madrid wrote that the hunger and hardship that caused the uprising would be better solved with knowledge, not violence. Madrid's republican paper La Justica agreed that "anarchists" were responsible. However, it called the military court's response an overreaction and a "political blunder." It said the government and press made the situation worse.

The angry anarchist newspapers showed the anger of the international anarchist movement. They warned of revenge. They said that the desperation caused by society led to the uprising. They also said that killing workers in response would only make relations worse and cause more hatred. Protests and attacks happened immediately after the executions and continued throughout the year. Spanish offices in Europe saw protests and clashes with police. Protests also happened across Spain, especially in Barcelona. An explosion in Barcelona's Plaza Real killed one person and injured others. There was also an attempted bombing of the Cortes parliament building in Madrid. Anarcho-communist newspapers in Catalonia encouraged and celebrated these attacks. However, anarcho-communist newspapers outside Catalonia were more peaceful or distanced themselves, blaming the attacks on the police instead.

Later, in September 1893, an anarchist named Paulí Pallàs tried to assassinate Arsenio Martínez Campos, a military general. Pallàs did this because of the general's role in the repression and executions after the Jerez uprising. The assassination attempt failed, and Pallàs was executed. This event led to a series of bombings in Spain throughout the 1890s.

See also

In Spanish: Sucesos de Jerez para niños

In Spanish: Sucesos de Jerez para niños