Mano Negra affair facts for kids

The Black Hand (Spanish: La Mano Negra) was a group that people believed was a secret organization of anarchists in the Andalusia region of Spain. It became known for murders, setting fires, and burning crops in the early 1880s. These events happened in 1882 and 1883. At that time, there was a lot of tension between different social classes in the countryside of Andalusia. Also, new ideas about anarchism were spreading, and there were disagreements within the Federación de Trabajadores de la Región Española (Workers' Federation of the Spanish Region).

Contents

Why the Black Hand Appeared

Between 1881 and 1882, there was a bad drought and poor harvests in Andalusia. This caused a lot of social tension and hunger. People started stealing, robbing, and setting fires. Some farms were raided, and riots broke out because people couldn't find work. Those protesting demanded that local councils give them jobs in public projects.

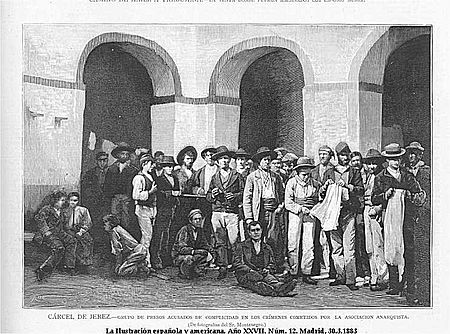

One serious riot happened on November 3, 1882, in Jerez de la Frontera. About 60 people were arrested when the Civil Guard (a police force) and the army stepped in. Landowners were scared of the rioters, but the rioters usually did not act violently towards people or farm guards.

Newspapers in Madrid, like El Imparcial, wrote about the tough lives of farm workers in Andalusia in late 1882. They described people looting bakeries and butchers because they were so hungry. The newspaper said people had to choose between begging, stealing, or starving. Leopoldo Alas also wrote about the hunger in Andalusia for the newspaper El Día.

By the end of 1882, the rains returned, and the farm workers of the new Federación de Trabajadores de la Región Española decided to go on strike. They wanted higher wages because a good harvest was expected.

The Story of the Black Hand

How the Black Hand Was "Found"

In early November 1882, a Civil Guard member in Western Andalusia sent the government some papers. These papers were supposedly the "rules" of a secret group called la Mano Negra, or "the Black Hand." The official report said these rules proved that the group was behind fires, cutting down forests, and murders in previous months.

These "rules" were two documents. One was called "The Black Hand: Regulation of the Society of the Poor, against their thieves and executioners, Andalusia." The other was just titled "Statutes." This second document did not use the name "Black Hand." Instead, it explained rules for a "People's Court" that would punish crimes by rich people. The first document specifically mentioned "the rich."

The government sent more Civil Guard officers to Cádiz province about two weeks after getting these documents. On November 21, 90 officers arrived in Jerez. With help from the local police, they arrested many farm workers and members of the FTRE. They believed these people were connected to the Black Hand. By early December, a newspaper reported that hundreds of "Black Hand internationalists" had been caught, along with their weapons and papers.

Within a few weeks, 3,000 farm workers and anarchists were put in prison. Some historians say the number was even higher: 2,000 in Cádiz and 3,000 in Jerez. Reports sent to the Ministry of Labor showed that most people were arrested just for being members of the Federación de Trabajadores (FTRE). The FTRE's newspaper, Revista Social, complained that their members were being arrested without good reason.

Were the Documents Real?

Historians have debated whether the documents the Civil Guard claimed to find under a rock were real. They also questioned if these documents truly proved the Black Hand existed. Manuel Tuñón de Lara thought the document seemed made up. He doubted it was legally or historically valid. Josep Termes wrote that the Black Hand was something the police created. He believed the Civil Guard's documents were actually older papers from a different collection.

Historian Clara Lida noted that the secret documents looked like ones from an earlier time. She said the name "Black Hand" would fit with other secret groups from the anarchist movement in Europe. Lida believed that bringing up old documents to make threats seem new was a trick. She thought it was done to make the public turn against the organized farm workers.

Juan Avilés Farré wrote that the documents were most likely real. However, he thought they came from two different, unknown groups. The first document, "The Black Hand," was probably found by the Jerez police years earlier. It was sent to the Minister of War and then forgotten. Someone likely brought it up again to try and solve the crimes in Jerez in 1882. This document did not mention the First International (a group of workers' organizations). The second document came from a secret period of the First International's Spanish Regional Federation, between 1873 and 1881.

Linking the Black Hand and the FTRE

The government, shop owners, and most newspapers (except El Liberal) tried to connect the Black Hand with the Federación de Trabajadores (FTRE). According to historian Clara Lida, they did this for two reasons. First, they wanted to stop the International's growing influence in Spain. Second, more locally, they wanted to prevent farm workers from organizing and striking before the harvest.

The FTRE's Federal Committee said they had no connection to the Black Hand. They repeated that they were against violence and would not support criminal groups. They stressed the difference between their growing workers' movement in Catalonia and the violent acts happening in Andalusia. However, the anarchist Peter Kropotkin's newspaper, Le Révolté, based in Geneva, supported the workers linked to the Black Hand. It criticized the FTRE for not showing solidarity with them.

In March, the FTRE's Federal Committee published a statement against the government's attempts to link their group with the Black Hand.

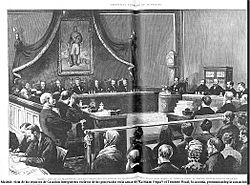

Court Cases

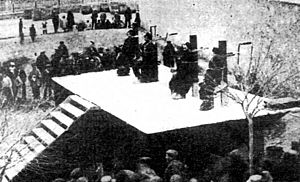

In June 1883, the court in Jerez sentenced seven people to death. Eight others were sentenced to 17 years and four months in prison. Two people were found not guilty. However, the prosecutor appealed the sentences to the Supreme Court. In April 1884, the Supreme Court decided that all but one of the accused should face the death penalty. Nine of these sentences were changed to jail time. But seven people were executed by garrote (a method of execution) two months later in Jerez de la Frontera's Plaza del Mercado. Three days later, the judges who made these decisions were honored by the Order of Isabella the Catholic.

In another case, involving the murder of innkeepers, one of the five attackers was shot dead at the crime scene. The other four were sentenced to death but were never executed. In the death of a ranch guard, two people were tried, and one received a long prison sentence.

After these events, the FRTE's newspaper, La Revista Social, showed support for workers. However, it did not support those who were condemned. The secret newspaper of Los Desheredados, an anarchist group that had left the FTRE, was sad that the Jerez executions were not challenged.

Campaign for the Prisoners

Almost 20 years later, in January 1902, an anarchist newspaper in Madrid called Tierra y Libertad started a campaign. They wanted to free the eight people who were still in jail. Soledad Gustavo, who was the partner of Joan Montseny, led this effort. Other newspapers in Europe, both anarchist and not, joined in. They held meetings in Paris, similar to those against the Montjuïc trial. They presented the prisoners as heroes of anarchism, saying they were among the first to fight social unfairness. They called them victims of a big crime against working-class people. Because of this, the group described the murdered people, like El Blanco de Benaocaz, as traitors and informants.

The prisoners wrote letters to newspapers, saying that their confessions were forced through torture. The Spanish government tried to fight this campaign until early 1903. Then, it changed the sentences to exile, meaning the prisoners had to leave the country.

What Happened Next

The third meeting of the FTRE, held in Valencia in October 1883, said that the Black Hand affair caused fewer people to attend. The group again protested attempts to link their organization with the Black Hand. They condemned groups that did illegal acts. They also agreed to break up their organization if they could not act legally.

Josep Llunas, a member of the FTRE Federal Committee, accused the government of using the Black Hand as an excuse to stop anarchists.

The Black Hand affair put pressure on the FTRE Federal Committee, which was based in Barcelona. They decided to distance themselves from the movement in Andalusia to avoid being blamed. They did not challenge the government's and newspapers' stories about the events. This made the Andalusian groups very angry. The result was a huge division within the FTRE. This division led to fewer members and the group breaking up five years later.

Different Views on the Black Hand

Historians have different ideas about whether the Black Hand organization truly existed. Tuñón de Lara believed there was no single organization. Instead, he thought there were small groups of anarchists who committed crimes. He said these groups were used to justify the harsh actions that led to the end of the FTRE. Termes called the whole affair a police setup, but he agreed that there was violence in rural Andalusia.

Avilés Farré argued that whether the Black Hand existed was less important than what happened because of it. He thought the documents were likely real. However, he said there was no actual activity linked to the group. There was also no proof that the group successfully formed or committed any crimes. If the group did exist, it left no trace. Even those found guilty of crimes linked to the Black Hand had never heard of the organization.

The police presented the found documents as proof of a big conspiracy. This conspiracy was supposed to explain the wave of violence happening across western Andalusia. The scary name "Black Hand" made it sound mysterious and appealing to journalists. Avilés Farré believed the documents were written by someone trying to start a secret group for class warfare. He thought it was likely by hidden members of the FTRE's local group in San José del Valle. However, the historian said there was no proof that the group actually started or carried out its threats.

The question of whether the Black Hand affair was a false flag (a trick to make it look like someone else did something) or just an unfounded government attempt to stop farm revolts was explored in a 1905 novel. This novel, La bodega, was written by Republican politician and writer Vicente Blasco Ibáñez.

Historian and journalist Juan Madrid wrote that governments often try to link anarchists to any crime. This is done to damage their reputation, and it has happened throughout history in Spain and around the world.

Legacy

The Black Hand story inspired a made-up South American guerrilla group in the comic series Condor. This comic was written by French writer Dominique Rousseau. Reading this comic, French-Spanish singer Manu Chao decided to name his band "Mano Negra." His father, Ramón, a journalist living in France after leaving the Francoist dictatorship, approved the name. He told Manu about the historical origins of the name.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: La Mano Negra para niños

In Spanish: La Mano Negra para niños