Jiuhuang Bencao facts for kids

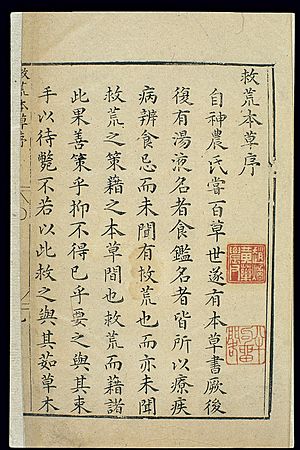

The Jiuhuang bencao (which means "Famine Relief Herbal" in Chinese) is a very old and important book from 1406. It was written by a Chinese prince named Zhu Su during the Ming dynasty. This book was the first of its kind to show pictures of wild plants that people could eat to survive during times of famine (when there isn't enough food). It was like a survival guide for finding food in nature.

Contents

Meet the Author: Prince Zhu Su

Prince Zhu Su was born in 1361. He was the fifth son of the Hongwu Emperor, who started the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Zhu Su was a very smart and talented scholar. He wrote poetry and even other medical books.

He became interested in botany (the study of plants) when he lived in Kaifeng. This area was often hit by natural disasters like floods, which caused famines.

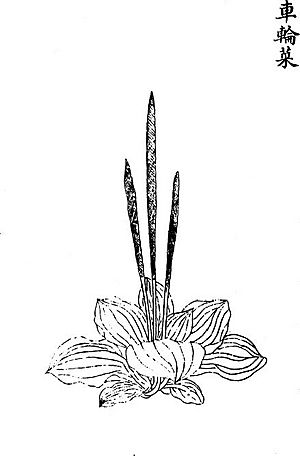

Prince Zhu Su spent many years researching and writing the Jiuhuang bencao from 1403 to 1406. He wanted to help people avoid suffering and death during famines. He even had special "famine gardens" where he grew and studied different plants. He hired artists to draw very realistic pictures of these plants for the book. These drawings were so good that some experts said they were better than European drawings from the 1600s!

What Does the Title Mean?

The title Jiuhuang bencao has two main parts.

- Jiùhuāng means "to help or rescue during a famine."

- Běncǎo usually means a book about herbal medicines. But in this case, it means a book about "herbal plants" that can be used as food.

So, the full title means something like "Herbal for Famine Relief." People have translated it in different ways, such as:

- "The Famine Herbal"

- "Treatise on Wild Food Plants for Use in Emergencies"

- "Materia Medica for the Relief of Famine"

Different Editions of the Book

The first edition of the Jiuhuang bencao was published in 1406. A scholar named Bian Tong, who worked for the prince, wrote an introduction for it. He explained that Prince Zhu Su had set up special gardens to test over 400 kinds of plants from fields and wild areas. The prince watched them grow and had artists draw them. He also wrote down which parts of the plants (like flowers, fruits, roots, or leaves) could be eaten.

Bian Tong wrote that people often forget about hunger when they have plenty of food. But when a famine hits, they don't know what to do. So, the prince wrote this book to help people prepare.

Over the years, many new versions of the Jiuhuang bencao were printed.

- In 1525, a governor named Bi Mengzhai ordered a second edition. The doctor Li Lian wrote a new introduction for it. He explained that plants look different in different places, and it's easy to confuse them. He said that making mistakes could be dangerous, even deadly. So, the book included pictures and clear descriptions to help people identify plants correctly and know how to prepare them safely.

- The third edition came out in 1555. Sometimes, later editions had fewer plants than the original 414. For example, one edition from 1562 left out almost half of the plants!

- After a bad famine in 1565, a man named Zhu Kun paid to have the original version republished in 1566. This version, reprinted in 1586, is the oldest one still kept in China today.

- The first Japanese version of the book was published in 1716.

In 1846, a French expert named Stanislas Julien shared a copy of the Jiuhuang bencao with the French Academy of Sciences. It was said that the Chinese government printed thousands of these books every year and gave them away for free in areas that often faced natural disasters.

What's Inside the Book?

The Jiuhuang bencao describes 414 different plants that could be used as famine foods.

- 138 of these plants were already known for both food and medicine from older books.

- 276 were new plants that hadn't been listed in Chinese medicine books before.

Prince Zhu Su organized the plants into five main groups:

- Herbs (245 kinds)

- Trees (80 kinds)

- Cereals (20 kinds)

- Fruits (23 kinds)

- Vegetables (46 kinds)

He also grouped them by which part of the plant could be eaten, such as leaves, fruits, or roots.

Many of the plants Zhu Su described became common foods in China, like taro and water-chestnut. Some even became popular in Japan or Europe, like watercress.

For example, the book describes the "arrowhead" plant, which is now a common food in China, especially during Chinese New Year. Zhu Su explained how it grows in water and described its leaves and roots. He suggested eating the young shoots after scalding them and adding oil and salt. It's interesting that he didn't mention eating the starchy root, which is the part commonly eaten today!

Important Safety Note: The Jiuhuang bencao was a great help, but some of its information isn't always perfect. For example, it mentions a plant called "marsh pea" and says you can boil its pods or peas to eat. However, it doesn't warn that eating too much of this plant, especially during a famine when it might be the only food, can cause a serious illness called lathyrism. This illness can lead to paralysis of the legs. This shows why it's important to be very careful and get expert advice before eating wild plants.

The "Esculentist Movement"

The Jiuhuang bencao started what some experts call the "Esculentist Movement" in China. "Esculent" means "edible" or "safe to eat." This movement was all about studying wild plants that were safe to eat during emergencies.

This movement lasted from the late 1300s to the mid-1600s. During this time, many other important books about edible wild plants were written, such as:

- The Yecai pu ("Treatise on Wild Vegetables") from 1524, which described 60 plants.

- The Shiwu bencao ("Food Herbal") from around 1550, which listed 400 plants.

- The Yecai bolu ("Encyclopedia of Wild Vegetables") from 1622, with 438 plants.

These books often included plants that weren't in the original Jiuhuang bencao. Experts believe that this movement was a huge help to people in China. There wasn't anything similar in Europe, Arabic countries, or India during that time. The first similar book in a European language didn't appear until 1783!

Why This Book is Important

Even though only a few Western scholars have studied the Jiuhuang bencao, they have praised Prince Zhu Su's 700-year-old book very highly.

One expert said it wasn't just a copy of older books but an original work based on the author's own experiences. Another called it "a valuable early book on Chinese botany" and the "earliest known, and still today the best" book on famine food plants. A famous historian of science, George Sarton, even called it "the most remarkable herbal of medieval times." He said that looking at Zhu Su's work, you can see how original and unique it was.

Today, the Jiuhuang bencao is still known as one of the most complete studies of famine food plants ever written.

See also

- Bigu (avoiding grains) – Ancient Chinese dietary practices that sometimes involved eating wild plants.

- Caigentan ("Vegetable Root Discourse") – A collection of wise sayings from 1590.