Kakiniit facts for kids

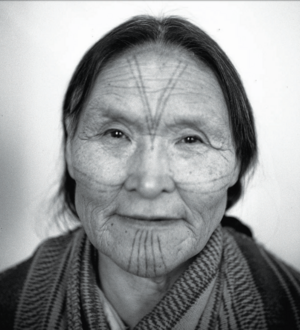

Kakiniit are special traditional tattoos of the Inuit people who live in the Arctic parts of North America. These tattoos are mostly worn by women, and women traditionally tattooed other women. Men could also get tattoos, but their designs were usually smaller.

Facial tattoos are called tunniit. They often marked a girl's journey into womanhood. Each tattoo has a unique meaning for Inuit women, telling a story or showing something important. Historically, these tattoos were for beauty, healing, religious reasons, and to help people reach a good afterlife.

During the 1900s, Christian missionaries tried to stop this practice. However, today, many Inuit women are bringing back kakiniit as a way to show pride in their Inuit culture. Groups like the Inuit Tattoo Revitalization Project are helping to make this happen.

Contents

What the Names Mean

The word Kakiniit (pronounced kah-kih-NEET) is an Inuktitut term for Inuit tattoos. If you're talking about just one tattoo, it's called kakiniq. The word tunniit (pronounced too-NEET) is used specifically for women's facial tattoos.

These words come from very old Inuit languages. For example, *kaki- means 'to pierce or prick'. This is why the word for tattoo in many Inuit languages is similar to kakiniq. The word tunniit for facial tattoos might come from an even older word meaning 'ornamental dots'.

What Kakiniit Look Like

Kakiniit are tattoos on the body, while tunniit are tattoos on the face. They all have special meanings. Tattoos were commonly placed on the arms, hands, chest, and thighs. Sometimes, women would have tattoos all over their bodies.

Only women received the extensive tattoos, and only women did the tattooing. Men's tattoos were much smaller and were often seen as good luck charms. Facial tattoos were an important part of a girl becoming a woman. It was believed that women could not marry until their faces were tattooed. These tattoos also showed that they had learned important skills for adult life.

The designs varied by region. Each pattern had a special meaning for the person wearing it. Some tattoos were given to celebrate big life events. For example:

- Y-shaped marks could represent tools used for seal hunting.

- V-shaped marks on the forehead often meant a girl was entering womanhood.

- Stripes on the chin could symbolize a girl's transition to womanhood.

- Chest tattoos were sometimes given after childbirth, showing motherhood.

- Marks on the arms and fingers often referred to the legend of Sedna, the sea goddess.

Because the practice was stopped for a while, some of the original meanings were lost. Today, many people who get these tattoos create new meanings for them as they bring the tradition back.

How Tattoos Were Made

Traditionally, tattoo artists were usually older women who were skilled in sewing. They used a special thread made from caribou sinew (a strong tissue). This thread was soaked in a mix of qulliq lampblack (soot from a lamp) and seal fat.

Then, the thread was poked under the skin using a needle made of bone, wood, or steel. Other tools like pokers and knives were also used. After the tattoo was finished, the area was cleaned with a mix of urine and soot to prevent infection.

Today, tattoos are often made using modern tattoo machines with needles and ink. However, some people still choose the traditional poking method to honor the old ways.

History of Kakiniit

Inuit stories about tattoos often connect to the sea goddess Sedna. The legend says that when her angry father threw her into the sea, he chopped off her fingers. These fingers then became sea animals. Tattoos on the hands and arms often represent this story, showing where her hands were cut.

In Inuit tradition, wearing kakiniit was believed to help women reach a happy afterlife. It was thought that women without hand tattoos might not be allowed into the afterlife by Sedna. Women without facial tattoos were said to go to a sad place where their heads would hang down forever.

Anthropologists believe that Inuit tattooing methods stayed the same for thousands of years. Very old tattoo evidence found in Alaska looks like tattoos seen on women in Greenland in the 1880s. This shows that the practice was widespread and unchanged before European contact.

Besides making people happy, tattoos were also used for other reasons:

- For healing, like acupuncture or pain relief.

- For beauty.

- For spiritual reasons, connected to shamans.

When Western medicine and fashion arrived, the first two reasons became less popular. The spiritual reasons were strongly discouraged by Christian missionaries.

In the early 1900s, the Catholic Church and missionaries banned kakiniit. They saw the practice as wrong because it was not Christian. For Inuit women, tattoos were a source of pride and a rite of passage. But missionaries saw them as shamanistic. Bible passages against tattooing were also used to pressure people to stop. An Anglican missionary named Edmund Peck, who spoke Inuktitut, was very effective in stopping many Inuit cultural and religious practices, including kakiniit. However, the practice did not completely disappear; it just went underground.

Bringing Kakiniit Back

Recently, there has been a strong movement to bring back kakiniit. This is happening because people want to preserve their culture and are worried the practice might disappear.

The Inuit Tattoo Revitalization Project, started in 2017 by Angela Hovak Johnson, is working to revive this tradition in Inuit communities. Johnson began the project when she learned that the last Inuk woman with traditional facial tattoos was very old, and the practice might die out with her.

The film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner helped bring more public attention to Inuit culture. Also, Inuit filmmaker Alethea Arnaquq-Baril made a 2010 film called Tunniit: Retracing the Lines of Inuit Tattoos. This film explores the history of the practice. For her film, Arnaquq-Baril interviewed 58 elders from 10 Inuit communities.

Many well-known Inuit people now wear traditional tattoos to show their pride in their heritage. These include Celina Kalluk, Lucie Idlout, Angela Hovak Johnston, Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory, Nancy Mike, and Johnny Issaluk. Mumilaaq Qaqqaq, who was elected to Parliament in 2019, also wears traditional facial tattoos.

See also

- History of tattooing

- Tavlugun

- Yidįįłtoo are the traditional face tattoos of the Hän Gwich’in.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |