Gwichʼin facts for kids

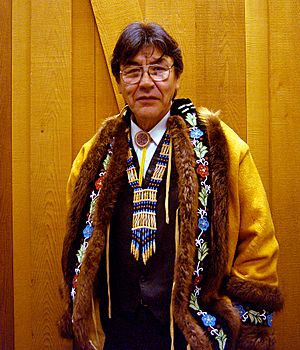

Former Grand Chief Clarence Alexander, Ecotrust Indigenous Leadership Award ceremony, Portland, Oregon, 2004

|

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Canada (Northwest Territories, Yukon) | 3,275 |

| United States (Alaska) | 1,100 |

| Languages | |

| Gwichʼin, English | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Alaskan Athabaskans and other Athabaskan peoples |

|

The Gwichʼin (say "Gwit-chin") are a group of First Nations people in Canada and Alaska Native people in the United States. They speak a language from the Athabaskan family. Most Gwichʼin live in northwestern North America, often above the Arctic Circle.

The Gwichʼin are famous for making things like snowshoes, birchbark canoes, and special two-way sleds. They are also known for their beautiful and detailed beadwork. They still create traditional clothes from caribou skin and use porcupine quills for embroidery. Today, the Gwichʼin mainly hunt, fish, and work in jobs that change with the seasons.

Contents

- What Does the Name Gwichʼin Mean?

- The Gwichʼin Language

- Gwichʼin Groups and Families

- Where Gwichʼin People Live

- Gwichʼin Stories and Traditions

- Traditional Beliefs

- Caribou: A Cultural Symbol

- Traditional Tattoos

- Plants Used by Gwichʼin

- Christianity Among the Gwichʼin

- Recognition of Gwichʼin Culture

- Current Issues and Politics

- See Also

What Does the Name Gwichʼin Mean?

The name Gwichʼin is sometimes spelled Kutchin or Gwitchin. It means "one who lives" or "resident of a region." In the past, the French called the Gwichʼin Loucheux, which means "squinters." They also used the terms Tukudh or Takudh. These names sometimes referred to specific ways of speaking the Gwichʼin language.

Gwichʼin people often call themselves Dinjii Zhuu instead of Gwichʼin. Dinjii Zhuu literally means "Small People." But it is used to refer to all First Nations people, not just the Gwichʼin.

The Gwichʼin Language

The Gwichʼin language is part of the Athabaskan language family. It has two main dialects: eastern and western. These dialects are roughly divided by the border between the United States and Canada. Each village has its own unique ways of speaking, special phrases, and expressions. For example, people in Old Crow, Yukon speak a dialect similar to those in Venetie, Alaska and Arctic Village, Alaska.

About 300 Gwichʼin people in Alaska speak their language. However, the UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger says that Gwichʼin is a "severely endangered" language. This means very few people still speak it fluently. There are fewer than 150 fluent speakers in Alaska and about 250 in northwest Canada.

People are working hard to keep the language alive. They are documenting the language and helping younger Gwichʼin speakers improve their writing and translation skills. For example, an elder named Kenneth Frank works with language experts and young Gwichʼin speakers. They are documenting traditional knowledge about caribou, including all the Gwichʼin names for caribou body parts.

Old place names show that the Gwichʼin have lived in this region for a very long time. They have likely been there since about 8,000 years ago.

Gwichʼin Groups and Families

The Gwichʼin people are made up of many different groups or tribes. Some of these include: Deenduu, Draanjik, Di’haii, Gwichyaa, Kʼiitlʼit, Neetsaii or Neetsʼit, Ehdiitat, Danzhit Hanlaii, Teetlʼit, and Vuntut or Vantee.

Three main family groups, called clans, have existed for a very long time across Gwichʼin lands. Two are primary clans, and the third has a lower status.

- The first clan is the Nantsaii, which means "First on the land."

- The second clan is the Chitsʼyaa, which means "The helpers" (second on the land).

- The last clan is the Tenjeraatsaii, meaning "In the middle" or "independents." This clan is for people who marry within their own clan. It is also for children whose parents are outside the clan system.

Where Gwichʼin People Live

About 4,500 Gwichʼin people live in 15 small communities. These communities are in the Northwest Territories and the Yukon Territory of Canada, and in northern Alaska.

Here are some of the Gwichʼin communities:

- Alaska

- Arctic Village (home to Dihai-kutchin and Neetsaii Gwichʼin)

- Beaver (Gwichyaa Gwichʼin)

- Birch Creek (Deenduu Gwichʼin)

- Chalkyitsik (Draanjik Gwichʼin)

- Circle (Danzhit Hanlaii Gwichʼin)

- Fort Yukon (Gwichyaa Gwichʼin)

- Venetie (Dihai-kutchin and Neetsaii Gwichʼin)

- Northwest Territories

- Aklavik (Ehdiitat Gwichʼin)

- Fort McPherson (traditional name: Tetlit Zheh, Tetlit Gwichʼin)

- Inuvik (This is the largest of the four Gwichʼin communities in the Gwichʼin Settlement Area. English is the main language, but schools teach Gwichʼin, and some local people still speak it.)

- Tsiigehtchic (formerly Arctic Red River) (Gwichyaa Gwichʼin)

- Yukon

Gwichʼin Stories and Traditions

The Gwichʼin have a strong tradition of telling stories. These stories have only recently started to be written down. Gwichʼin folk stories include the "Vazaagiitsak cycle." These stories are about the funny adventures of a Gwichʼin misfit. Other important characters in Gwichʼin stories are Googhwaii, Ool Ti’, Tł’oo Thal, K’aiheenjik, K’iizhazhal, and Shaanyaati’.

Many folk tales about ancient times begin with the phrase Deenaadai’', which means "In the ancient days." This is usually followed by saying that this was "when all of the people could talk to the animals, and all of the animals could speak with the people." These stories often teach lessons about how Gwichʼin people should behave. Themes often include equality, generosity, hard work, kindness, mercy, working together, and fair revenge. Examples of these stories are "Tsyaa Too Oozhrii Gwizhit" (The Boy In The Moon), "Zhoh Ts’à Nahtryaa" (The Wolf and the Wolverine), and "Vadzaih Luk Hàa" (The Caribou and the Fish).

Traditional Beliefs

Important people who have represented traditional Gwichʼin beliefs in recent times include Johnny and Sarah Frank, Sahneuti, and Ch’eegwalti’.

Caribou are a very important part of First Nations and Inuit stories and legends. The Gwichʼin have a creation story about how Gwichʼin people and the caribou came from the same being. There are many woodland caribou in the Gwichʼin Settlement Area. Woodland caribou are an important food source for the Gwichʼin, even though they hunt them less often than other caribou. Gwichʼin living in Inuvik, Aklavik, Fort McPherson, and Tsiigehtchic hunt woodland caribou. However, they prefer to hunt Porcupine caribou or the barren-ground Blue Nose herd when they are available. These herds travel in large groups. Many hunters say that woodland caribou, which form very small groups, are wilder and harder to find and hunt. They are very smart and hard to catch.

Caribou: A Cultural Symbol

The caribou, called vadzaih, is a very important cultural symbol for the Gwichʼin. It is like the buffalo for the Plains Indians. Sarah James, a Gwichʼin elder, said, "We are the caribou people. Caribou are not just what we eat; they are who we are. They are in our stories and songs and the whole way we see the world. Caribou are our life. Without caribou we wouldn't exist."

Traditionally, Gwichʼin tents and most of their clothes were made from caribou skin. They lived "mostly on caribou and all other wild meats." Caribou fur skins were used as bedding and flooring. Soap was made from boiled poplar tree ashes mixed with caribou fat. Drums were made from caribou hide. Overalls were made from "really good white tanned caribou skin."

Elders have identified at least 150 Gwichʼin names for all the caribou's bones, organs, and tissues. Along with these names, there is "an encyclopedia of stories, songs, games, toys, ceremonies, traditional tools, skin clothing, personal names and surnames, and a highly developed ethnic cuisine."

Traditional Tattoos

Yidįįłtoo are the traditional face tattoos of the Hän Gwich’in people.

Plants Used by Gwichʼin

In 2002, the Gwichʼin Social and Cultural Institute, the Aurora Research Institute, and Parks Canada published a book. It was called Gwichʼin Ethnobotany: Plants Used by the Gwichʼin for Food, Medicine, Shelter and Tools. This book, made with the help of elders, described many trees, shrubs, berry plants, and other plants that the Gwichʼin used. For example, black spruce and white spruce, called Ts’iivii, were used for "food, medicine, shelter, fuel and tools." Boiled cones and branches were used to prevent and treat colds.

Christianity Among the Gwichʼin

Christianity came to Gwichʼin lands in the 1840s. This led to spiritual changes that are still seen today. Many Gwichʼin people became Christian, influenced by Anglican and Catholic missionaries. These two Christian groups became the main ones among the Gwichʼin. Important people in this missionary movement were Archdeacon Hudson Stuck, William West Kirkby, Robert McDonald, Deacon William Loola, and Deacon Albert Tritt. The Traditional Chief of one Gwichʼin village, the Rev. Traditional Chief Trimble Gilbert of Arctic Village, is also an Episcopal priest. Chief Gilbert is recognized as the Second Traditional Chief of all the Athabascan tribes in Interior Alaska.

The Takudh Bible is a translation of the entire King James Bible into Gwichʼin. This Bible uses an older way of writing that is not very accurate and hard to read. In the 1960s, Richard Mueller created a new way to write Gwichʼin, which is now the standard.

Recognition of Gwichʼin Culture

On April 4, 1975, Canada Post released two stamps in the "Indians of Canada, Indians of the Subarctic" series. Both were designed by Georges Beaupré. One stamp showed "Ceremonial Dress" based on a painting by Lewis Parker of a "ceremonial costume of the Kutchin tribe" (Gwichʼin people). The other stamp, "Dance of the Kutcha-Kutchin," was based on a painting by Alexander Hunter Murray.

Current Issues and Politics

Caribou are a very important part of the Gwichʼin diet. Many Gwichʼin people rely on the Porcupine caribou herd. This herd has its babies on the coastal plain in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). Gwichʼin people have been very active in protesting and speaking out against the idea of oil drilling in ANWR. They worry that oil drilling will harm the Porcupine Caribou herd.

Bobbi Jo Greenland Morgan, who leads the Gwichʼin Tribal Council, has shared concerns with the United States. The Canadian government, the Yukon and Northwest territories, and other First Nations also worry about plans to allow energy drilling in the caribou's calving grounds. This is despite international agreements to protect the herd. In December, the United States released a plan for oil leases with a public comment period. Environment Canada wrote a letter to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Alaska office. It said that "Canada is concerned about the potential impacts of oil and gas exploration and development planned for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Coastal Plain."

For similar reasons, Gwichʼin people also protested against oil development in the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge. They also opposed a proposed land trade involving the United States Wildlife Refuge system and Doyon, Limited.

See Also

In Spanish: Kutchin para niños

In Spanish: Kutchin para niños

- Arctic Son

- Oil on Ice

- Being Caribou