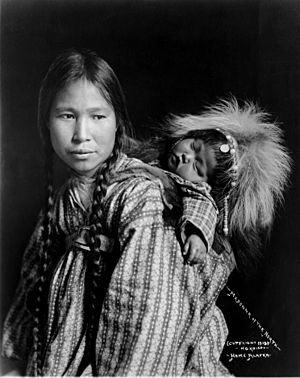

Inuit women facts for kids

The Inuit are Native people who live in the very cold Arctic and subarctic areas of North America. These regions include parts of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. The Inuit are related to the Iñupiat from northern Alaska and the Yupik from Siberia and western Alaska, as well as the Aleut people. The word "Eskimo" used to describe these groups, but it is not used much anymore.

In Inuit communities, women have always been very important for the group to survive. The jobs and duties of Inuit women were seen as just as important as those of men. Because of this, women were respected and had an equal say in many things.

Today, with modern changes and people moving to towns, traditional Inuit culture has changed. This has also changed the role of women. These changes have brought both good and bad effects for Inuit women.

Contents

Family Life and Marriage

In traditional Inuit culture, marriage was not just about choosing someone you loved. It was a necessary partnership for survival. Inuit men and women needed each other to live through the very tough Arctic conditions. Because everyone relied on a partner, marriages were often planned when children were born. This helped make sure the family would survive. While love marriages happened, most were still planned because there were not many people to choose from. A young woman could marry after puberty, but a man had to show he was a good hunter first. He needed to prove he could feed a family.

Inuit marriages usually did not have big ceremonies. Couples were often seen as married after their first child was born. Some marriages were between two people, and some were between more than two people. However, a man having many wives was rare because it was hard to support more than one. Families would exchange gifts before marriages, but there was no official payment for the bride or groom. Even though men were often seen as the head of the family, both men and women could ask for a divorce. But divorce was not common because it was bad for the family and the whole community.

Sometimes, spouses were traded or exchanged between families. Women had some say in this process. This was a common way to avoid divorce, as it made sure no family was left without a mother or wife, who were vital for survival. In Inuit culture, the family was often linked to the kudlik (lamp) or hearth. This lamp belonged to the wife and was her responsibility. It had a very special meaning for the family, community, and culture.

Food and Cooking

Hunting and fishing were the main ways Inuit people got food. Men traditionally did most of the hunting. Women's jobs included gathering other foods, like eggs and berries. They also prepared the food the hunters brought back. Seals, walrus, whales, and caribou were common animals hunted by the Inuit. Animals killed by hunters had to be cut up and frozen quickly. This was done before they spoiled or froze solid before being butchered. Women were traditionally in charge of cutting up, skinning, and cooking the animals.

In Inuit culture, people believed that if women respected the animals killed during hunts and took good care when butchering them, it would lead to successful hunts in the future. Food and other resources were often shared throughout the community when needed. Women were responsible for sharing food with families in the community.

The Inuit moved with the seasons to find the best hunting spots. Whole families often moved together. Because of this, tools for hunting and cooking had to be light and easy to carry. Some Inuit groups developed clever tools. These included light, strong metal harpoons and wood stoves, which were used by the late 1800s.

Children and Motherhood

Having children and taking care of them were two of the most important jobs for an Inuit woman. Inuit parents showed a lot of love and care to their children. Inuit children usually started helping their family and community by age 12. They would pick berries or hunt small animals. During this time, they learned skills from their parents by watching closely. Learning by watching was the best way. It was not practical for children to practice by sewing valuable skins or joining men on important hunts.

Women raised both boys and girls. Men taught boys certain skills, like hunting. Women taught girls skills, like sewing.

Kinship is very important for an Inuit child's cultural identity. From birth, children learn about their duties and family ties. One way the Inuit do this is through a practice called name-soul. After a family member passes away, their name is given to a child in the same family line. The name gives a child a cultural link, a sense of belonging, and their own identity. Also, name-soul allows past family members to continue their legacy. Children are raised in a family-focused way. Their name reminds them that the group comes first. There were no separate boy's and girl's names in Inuit culture. So, it was common for a girl to have her grandfather's name, for example.

Children were taught early on to listen to their parents and respect elders. They were given more freedom than non-Inuit children. Too much discipline was seen as unhelpful. So, children were rarely punished for mistakes. Learning was seen as a team effort between child and adult. Children were guided through life rather than directly taught or lectured.

Adoption was very common in Inuit culture and often informal. Babies who were not wanted, or babies a family could not support, could be offered to another family. If the other family agreed, the adoption was complete.

Pregnancy and Birth Beliefs

Young women often learned about their first pregnancy from their mother or grandmother. Elders could tell by "looking into the face" or feeling the stomach. Once a woman knew she was pregnant, it was important to tell her mother, husband, and close community right away. The Inuit believed her condition needed special care to keep the mother, baby, and camp healthy.

To prevent miscarriage, the husband and camp made sure the woman was not stressed or tired. The husband was not allowed to get angry with his wife during pregnancy. If a miscarriage happened, the woman had to tell her mother and the camp right away. Hiding it was believed to bring bad luck, like hunger or illness.

Traditional Inuit beliefs, called pittailiniq, guided women's care during pregnancy. These rules were passed down through generations. They helped prevent problems, promote a healthy birth, and ensure the baby had good qualities. For example, women were told to stay active during pregnancy. Being lazy was thought to make labor harder. There were also rules about massaging the stomach so the baby would not "stick" to the uterus.

Elders shared many pittailiniq about a woman's actions during pregnancy. For example, they were told to go outside quickly in the morning for a short labor. They should not lie around too much, or labor might be long. They were also told not to tie ropes around their hands when stretching sealskin. This was to prevent the umbilical cord from wrapping around the baby's neck.

There were also pittailiniq about how a pregnant woman should behave. For instance, if asked to do something, she should do it right away for a speedy delivery. She should finish any project, like sewing, or labor would be longer. She should not scratch her stomach to avoid stretch marks. She should untie everything tied up to help with dilation during birth.

The Inuit also had many pittailiniq about diet during pregnancy. Pregnant women were told not to eat raw meat. They should only eat boiled or cooked meat. Men also followed this rule when with their wives. Pregnant women always got the best pieces of meat and food. These rules also linked diet to the baby's beauty. For example, finishing a meal and licking the plate was believed to make the baby beautiful. Eating caribou kidneys was thought to ensure beautiful babies.

Preparing for Birth

Women were not taught how to prepare for birth beforehand. They trusted they would get instructions from their midwife and other helpers, like their mother. When labor seemed close, the woman and her helpers would set up a soft bed of caribou skins or plants. A thick layer of caribou fur was good for soaking up blood.

Ideally, birth happened with a helper and a midwife. But because of hunting, many births happened while traveling or at a hunting camp. In these cases, men might help, or the woman might give birth alone. Women often did not know who their midwife would be until birth.

A midwife (Kisuliuq, Sanariak) was a highly respected woman in the community. She gained experience by helping her mother or other midwives. Midwives comforted the woman, knew her body, told her what to expect, helped her change positions for quick deliveries, and dealt with problems.

Sometimes, an angakkuq (spiritual healer) would get involved. If the midwife thought there was a "spiritual problem," the angakkuq would try to fix it to bring back balance and normal birth.

During Labor and Birth

Labor and birth were big celebrations in the Inuit community. When a woman started contractions, her midwife would gather other women to help. Other signs of labor included discharge, water breaking, or stomachache. Even though it was a celebration, labor was a quiet and calm time. The midwife would often whisper advice. If the woman followed traditions during pregnancy, her labor was expected to be quick and easy. Women were often expected to continue daily chores until late in labor. They endured pain without pain relief.

The midwife tried to keep the woman calm and active. They encouraged position changes. Women labored in different positions, like lying on their side, squatting, or standing. A caribou pelt was placed under the woman. Some communities used ropes to pull on or a box to lean over to ease pain. There was little use of medicine for pain. Traditionally, the woman had to keep her spine straight. The midwife might use a wooden board to keep her back aligned. A rolled towel or wood block kept the legs apart, which midwives believed sped up labor.

During birth, the midwife mostly handled everything. But the woman was active and followed her body's cues for pushing and resting. When ready to push, the midwife told her to pull her hair and bear down. Most Inuit women gave birth at home. Some Alaskan communities had special birthing huts (aanigutyak). If not, the place where the woman gave birth had to be left empty.

Once the baby was born, the midwife cut the umbilical cord with a special knife and tied it with caribou sinew. Sinew had a lower risk of infection. The cord was left long enough to pull out the placenta if needed. After the baby was born and the placenta was ready, many midwives told the woman to get on her hands and knees and push. Midwives also massaged the stomach to reduce bleeding after birth. Some Inuit communities wrapped the placenta in cloth and buried it in the tundra rocks.

After Birth and the Newborn

There is not much information about the time right after birth (postpartum) in traditional Inuit practices. One elder midwife said her mother-in-law briefly helped with house chores until she felt better. But she also said she felt better quickly and eagerly did chores behind her mother-in-law's back.

Women who could breastfeed did so right after birth, often for two years or longer. Breastfeeding was their only way to space out births.

The birth of a newborn was a cause for celebration. Everyone, including children, would shake hands to welcome the baby. It was believed that if the mother followed the pittailiniq during pregnancy, the child would be healthy and have a good life.

Right after birth, the baby was checked for breathing. If not breathing, the midwife would hang the baby upside down by its feet and slap its bottom. The midwife also removed mucus from the baby's mouth to help it "fatten up." The umbilical cord stump was covered with burnt arctic moss. The baby was placed in a rabbit fur or cloth pouch. This pouch kept the baby warm, acted as a diaper, and protected the healing cord stump. It was believed the cord stump should fall off on its own. If the mother found it, the child would become very active around age four. Babies were not usually washed after birth.

By one year of age, elders said children were toilet trained.

Also right after birth, a special person, often the midwife, determined the baby's gender. This person became the baby's sanaji (for a boy) or arnaliaq (for a girl). This person had a lifelong role in the child's life. If the baby was a boy, he would later call this person his arnaquti and give her his first catch as a child. The sanaji also cut the umbilical cord, provided the baby's first clothes, named the child (tuqurausiq), blessed the child (kipliituajuq), and gave the child desired traits. It was believed that a child's path was set from early life. These practices were highly valued as they shaped the child's future.

In rare cases, a child might be considered sipiniq (Inuktitut: ᓯᐱᓂᖅ). This meant the baby was believed to have changed physical sex from male to female at birth. This idea was mainly found in parts of the Canadian Arctic, like Igloolik and Nunavik. Sipiniq children were treated as socially male. They would be named after a male relative, do male tasks, and wear men's traditional Inuit clothing. This usually lasted until puberty, but sometimes continued into adulthood, even if the sipiniq person married a man.

Once checked by the midwife or sanaji, the baby was quickly given to the mother to start breastfeeding. Elders said the baby stayed in almost constant physical contact with its mother from birth. It slept on the family platform, rode in the amauti (baby carrier worn by the mother), or was nestled in her parka for feeding.

Naming the Newborn

The tuqurausiq was a very important naming practice done by the sanaji or midwife. It linked the child to a relative or a family friend who had passed away. The Inuit believed that when a baby was born, it took on the soul or spirit of a recently deceased relative or community member. Through the name, the child literally took on the relationship of the person they were named after. For example, if a child was named after someone's mother, family members would call that child "mother." They would give the child the same respect given to that mother. The baby's name also affected its behavior. The Inuit believed that crying meant the baby wanted a certain name. Often, once named, the baby would stop crying. Also, since the baby or child represented their namesake, they were thought to know what they wanted or needed, like when they were hungry or tired. Because of this belief, it was considered wrong to tell a baby or child what to do. It was like telling an elder or adult what to do, which was against Inuit social rules. When a baby or child acted like the person they were named after, it was called atiqsuqtuq. Children today are still named after family members, but the name might be an English one instead of a traditional Inuit name.

Other Responsibilities

Besides having and raising children, women were also responsible for sewing skins to make clothes. They preserved, processed, and cooked food. They cared for the sick and elderly. They also helped build and take care of the family's home. Warm, light, and useful clothing was perhaps the greatest achievement of the Inuit. For protection against the harsh Arctic winter, it has not been beaten by even the best modern clothing.

The clothing made by women was vital. Life in the Arctic was not possible without extremely well-made clothes to protect from the bitter cold. The clothing was made by carefully sewing animal skins and furs using ivory needles. These needles were very valuable. The process of preparing skins for sewing was done by women and was very hard work. Skins had to be scraped, stretched, and softened before they were ready to be sewn.

Inuit women also helped build and care for homes. These could be igloos, semi-underground sod houses, or tents in the summer. This needed knowledge of building and how to keep warm. A lot of strength was needed to build Inuit shelters. Because of this, Inuit women often worked together and asked men for help to build their homes. For both practical and social reasons, these houses were built close together. Or they were made big enough for more than one family to live in.

Status in Inuit Culture

Different Jobs, Equal Respect

Jobs in Inuit culture were not seen as just "men's work" or "women's work." Instead, the Inuit believed in men's skills and women's skills. For example, hunting was usually done by men. Sewing clothes, cooking, preparing food, gathering food (not hunting), and caring for the home were usually done by women. This does not mean women never hunted, or men never helped with other jobs. This was just how the work was traditionally divided.

Women hunted and boated for fun, or when food was scarce and the community needed more hunters. Men and women worked together to make their culture function well. Men could not go hunting without the warm clothes women sewed for them. And women would not have enough food without the meat men brought back from their hunts.

Because of this, the work done by women was respected just as much as the work done by men. While men and women generally did different jobs, one type of work was not seen as better or more important than another. It might seem like men did less work because they mainly hunted. But hunting was extremely hard physically and took a lot of time. It often meant traveling for days or weeks. So, the way jobs were divided in Inuit culture meant that both men and women did a similar amount of work.

Power and Influence

While women were respected by men and often treated as equals, they did not have equal power in the community. Important decisions, like when and where to move, were made only by men. The Inuit had very little government. But some groups had tribal councils or groups of elders who made decisions for the community. These councils were almost always made up of men.

Because of this, Inuit women had little to no say in some of their communities' most important decisions. Men usually had the final say in things like arranging marriages and adoptions. Even though women had a fairly high social position and controlled their own homes, their power was usually limited to those areas. They also had important ceremonial jobs, like lighting and tending lamps and sharing food.

Also, if men were unhappy with how a woman handled her duties, they could take over her work. Or they could give her work to another woman they thought was more capable. With women having less power, they were sometimes in difficult situations when they were not part of the decision-making. For example, a pregnant woman or a woman with a newborn might not be able to travel hundreds of miles in the Arctic to find better hunting grounds. These factors were rarely considered when men were the only ones making decisions for a community.

Modern Changes for Inuit Women

After meeting other cultures, the Inuit learned about new technologies and modern ways of life. This changed their lives a lot. The Inuit are now a modern people. Like almost all Native groups, they no longer live exactly like their ancestors. This is especially true for Inuit women.

New Roles in Culture

After modernization, the Inuit started moving into Arctic towns. They began to work for wages, for the government, and on community councils. They also got modern clothes, homes, and vehicles. Inuit men first led the way in adapting. They learned the language of the new cultures and took on modern, wage-earning jobs. However, a lack of education started to make it hard for men to find and keep jobs.

Because of this, women began to lead the way in adapting to new ways. Women started finding work as house helpers, store clerks, hospital aides, classroom assistants, and interpreters. They also worked in weaving and knitting shops. Inuit women tend to go to school more than Inuit men, especially college. Some universities in Inuit regions, like the Nunavut Arctic College, have programs just for the Inuit. Women use these programs much more often than men.

Because Inuit women seek more education and better jobs, they have increasingly become the main earners for their families. This has caused men to take on duties in the house that women traditionally did, like raising children and keeping the home in order.

Changes in Status and Power

The "role reversal" happening in Inuit society has given women a big increase in power and influence. Women have started to seek more power for themselves. This includes making decisions in the family and for the culture as a whole. As the main wage earners, working women are now often seen as the heads of their families. They have more say in family decisions. This has made relationships between Inuit men and women more complex. Some men have started to feel upset that women are "taking their rightful place as the head of the family."

Another change is that Inuit women have increasingly started to run for political office. While the positions they seek are often at the community and local levels, this increase in activism shows the new confidence Inuit women have found in the modern world.

The second premier of Nunavut was a woman, Eva Aariak. She was one of two female members of the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut at the time. Other women in elected positions include Elisapee Sheutiapik, also a member of the assembly, and Madeleine Redfern, both mayors of Iqaluit. Three out of four members of parliament for the Nunavut area have been women: Nancy Karetak-Lindell, Leona Aglukkaq, and Mumilaaq Qaqqaq.

Health Changes

Scientists have found that Inuit people seem to have more illnesses and health problems than other groups. This is especially true for women and children, and it has become more noticeable after modernization. One possible reason is that the traditional Inuit diet was high in fat and protein but low in fruits and vegetables.

More likely reasons include changes in diet after modernization. Also, there is less physical activity as traditional jobs like hunting and building homes are done less often. Whatever the cause, diabetes, heart disease, and high cholesterol are common health problems for the Inuit. Studies have shown that these issues are worse for women than for other groups.

There is a lot of pressure for Inuit women to look and act like people in modern Western cultures. However, many parts of modern culture are new to Inuit women. They can clash with their traditional practices.

See also

- Inuit art

- Inuit languages

- Inuit religion

- Lists of Inuit

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |