Kihansi spray toad facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kihansi spray toad |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Kihansi spray toad at the Toledo Zoo | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Bufonidae |

| Genus: | Nectophrynoides |

| Species: |

N. asperginis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Nectophrynoides asperginis Poynton, Howell, Clarke & Lovett, 1999

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

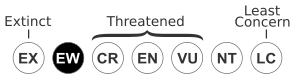

The Kihansi spray toad (Nectophrynoides asperginis) is a small toad that only lived in one special place in Tanzania. These toads give birth to live young, unlike most frogs and toads that lay eggs. They also eat insects. Sadly, the Kihansi spray toad is now listed as Extinct in the Wild by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This means they no longer live freely in nature. However, some of these toads are still alive in zoos and special breeding programs.

Contents

How the Kihansi Spray Toad Looks

The Kihansi spray toad is a small amphibian. Males and females look a bit different, which is called being sexually dimorphic. Females can grow up to about 2.9 cm long. Males are smaller, reaching about 1.9 cm.

These toads have yellow skin with brownish spots. Their back feet have webbing between the toes. But they do not have wide toe tips like some other frogs. They also do not have outside ears, but their inner ears work normally.

Female toads often have duller colors. Males usually have more noticeable markings. Males also have dark patches on their sides where their back legs meet their bellies. The skin on their bellies is clear. This means you can often see the baby toads growing inside pregnant females. These toads breed using internal fertilization. The female keeps the young inside her body until they are born.

Where the Kihansi Spray Toad Lived

Before they disappeared from the wild, Kihansi spray toads lived in a very small area. This was a 2-hectare (about 5-acre) spot. It was at the bottom of the Kihansi River waterfall in the Udzungwa Mountains of Tanzania. The Kihansi Gorge is about 4 km (2.5 miles) long.

The toads' home was made of several wet areas. These areas were kept moist by the spray from the waterfall. They had thick, grassy plants like Panicum grasses and Selaginella kraussiana clubmosses. The areas near the waterfall spray always had the same temperature and 100% humidity. Today, there is a special sprinkler system. It tries to copy the wet conditions that the toads needed. No other groups of these toads have been found anywhere else.

Why They Disappeared from the Wild

Before they became extinct in the wild, there were about 17,000 Kihansi spray toads. Their numbers naturally went up and down. In May 1999, their population was high. It dropped in 2001 and 2002. Then it went up again in June 2003 to almost 21,000 toads. But after that, their numbers fell very quickly. By January 2004, only three toads could be seen.

The species was listed as Extinct in the Wild in May 2009. The main reason for this was losing their habitat. This happened after the Kihansi Dam was built in 1999. The dam cut the amount of water flowing over the waterfall by 90 percent. This greatly reduced the water spray, especially in the dry season. It also changed the types of plants growing there.

The toads needed this water spray to survive. The special sprinkler system meant to help them was not ready when the dam opened. In 2003, the toad population crashed for good. This happened when the sprinkler system broke down during the dry season. Also, a disease called chytridiomycosis appeared. And the Kihansi Dam was briefly opened to wash out dirt. This dirt contained pesticides from farms upstream. The last time a wild Kihansi spray toad was seen was in 2004.

Helping the Kihansi Spray Toad

Protecting Their Home

Between 2000 and 2001, special sprinkler systems were built. They were placed in three wet areas affected by the Kihansi Dam. These systems were made to create the fine water spray that was there before the dam. This helped keep the toads' tiny habitat wet.

At first, the sprinklers worked well. But after 18 months, some of the original plants died back. Weedy plants took over the area. This changed the types of plants growing there. Next steps included watching the environment and making sure there was enough water for the toads.

Breeding in Zoos

Zoos in North America have a special breeding program. This program is called ex situ, which means "off-site" or outside their natural home. The goal is to bring the toads back to the wild one day. The Bronx Zoo started this program in 2001. Almost 500 Kihansi spray toads were brought from Tanzania to six U.S. zoos. This was done to save them from disappearing completely.

At first, it was hard to keep them alive in zoos. Only the Bronx Zoo and Toledo Zoo could keep them going. By December 2004, fewer than 70 toads were left in captivity. But when scientists learned exactly what the toads needed, more of them survived and bred.

In November 2005, the Toledo Zoo opened an exhibit for the Kihansi spray toad. For a while, it was the only place where people could see them. The Toledo Zoo now has thousands of these toads. Most of them are not on public display. The Bronx Zoo also has thousands and opened a small exhibit in 2010. In 2010, the Toledo Zoo sent 350 toads to the Chattanooga Zoo. Other zoos like the Detroit Zoo and Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo also have hundreds of them.

Bringing Them Back Home

In August 2010, 100 Kihansi spray toads were flown from the Bronx Zoo and Toledo Zoo back to Tanzania. This was part of a plan to reintroduce them to the wild. They went to a special breeding center at the University of Dar es Salaam.

In 2012, scientists sent a test group of 48 toads back to the Kihansi gorge. They found ways for the toads to live even with the chytrid fungus. This fungus was thought to be in the soil there. Researchers mixed soil from the gorge with captive toads. They also used other toad species from the wild. The reintroduction began because the soil seemed safe. In 2017, a larger reintroduction program was planned. A few Kihansi spray toads have been successfully returned to Tanzania.

Even with careful rules in the breeding centers, the toads sometimes get sick from the chytrid fungus. This has caused many deaths at the Kihansi facility. Problems with air conditioning and water filters have also led to toad deaths. Scientists believe it will take time for the toads to fully return to the wild. They need to learn how to find food, avoid predators, and fight off diseases on their own. This is very different from their safe life in captivity.