Klondyke mill facts for kids

Klondyke Mill was a special factory that processed ore (rock containing valuable metals) in north Wales. It was located on the edge of the Gwydir Forest, near Trefriw.

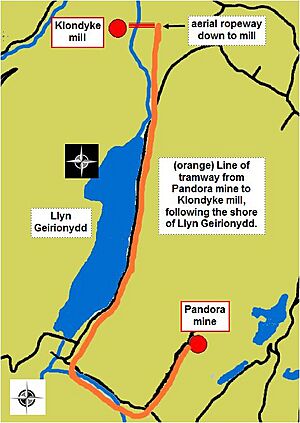

The mill was built in 1900 to handle lead ore and some zinc ore. This ore came from the Pandora mine, about 2 miles away. A special railway, called a tramway, carried the ore to the mill. It followed the eastern side of Llyn Geirionydd lake.

However, Klondyke Mill wasn't used much. The Pandora mine never made money after the mill was built. The mine closed in 1905, and Klondyke Mill shut down in 1911. It had a few different owners who hoped it would be successful, but it wasn't.

In the 1920s, the mill became famous for a big money-making trick. People were asked to invest in the "Klondyke mine," which was supposedly full of silver. This trick is why the mill is now called Klondyke Mill. Before that, it was known as Geirionydd Mill or the New Pandora Lead Works.

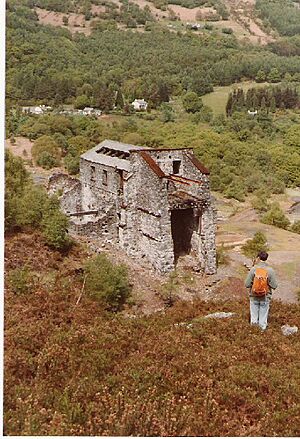

Today, the mill is in ruins. It reminds us of the false hopes from that time. It's thought to be the biggest old building related to lead mining still standing in north Wales. It's a protected ancient monument. Even though it's falling apart, Cadw (a Welsh heritage organization) looks after it. It's the only mine building in the Gwydir Forest that Cadw protects.

Contents

Mill History and Building

The Welsh Crown Spelter Company built Klondyke Mill in 1899. This company was connected to the English Crown Spelter Company, which needed a lot of blende (a type of zinc ore). The Welsh company bought several mines, including Pandora mine. They also started a smaller mine called Klondyke, right next to where the mill was built.

The company had big plans for Pandora mine. They wanted to build a large new mill at Klondyke. Ore would travel 2 miles on a tramway to the mill. Then, it would slide down an aerial ropeway from the hillside into the mill's top floor. The company even had a special petrol train to move things on the tramway.

Both Pandora and Klondyke were meant to be very modern. They would use a lot of electricity. Water from nearby lakes and streams powered generating stations. This water traveled through pipes and channels (called leats) to power the mill's machinery.

In 1901, an engineer named George Grant Francis reported on the progress. He said they had built water tanks and pipelines. They had also laid miles of tram lines and built the mill house. The mill was designed to process about 60 tons of ore in 10 hours.

The main walls of the mill building have strong supports called buttresses. It's not clear if these were part of the original plan or added later. They were definitely needed because one side of the building was made of wood and metal sheets. Inside, the mill had machines like a stone-breaker and jigs to process the ore. There was also a special room for the turbine that generated power.

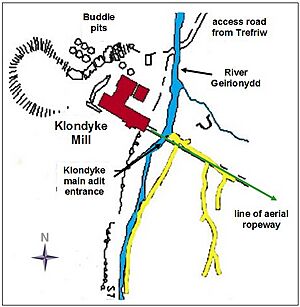

A new road was built to access the mine and mill. This road is now a public footpath. It crossed the river Geirionydd over a bridge. The bridge platform is gone, but its side walls are still there.

Klondyke Mine Details

The Klondyke mine was right next to the mill, across the river. It had one main tunnel, called an adit, heading southeast. This tunnel was directly below the aerial ropeway that went to the mill. There must have been a bridge with rails connecting the mine entrance to the mill.

Just inside the mine entrance, the main tunnel split into several shorter tunnels. This showed they planned to expand the mine in many directions. However, this didn't happen. Inside, three tunnels went off to the right, generally south. The first tunnel was the longest. All these tunnels showed signs of minerals.

Besides this main mine, Klondyke mine also included smaller tunnels upstream in the Geirionydd gorge. Some of these were part of the Bryn Cenhadon Mine.

Why the Mill Failed

After the mill was built, company owners were told that the future looked bright. They were told that there were huge amounts of ore, much more than first thought. These hopeful words were probably meant to keep the investors happy.

However, in 1901, two years after the mill was finished, it still wasn't making any money. The engineer, George Grant Francis, blamed this on problems with the new machinery. He said the mill needed time to work properly. He believed it would soon work well and cheaply. He also said that even with low metal prices, they would make a good profit. He was very proud of the mines and mill, calling them the most modern in the United Kingdom.

Despite Francis's hopeful words, investors were worried. A lot of money was being spent on developing Pandora mine and Klondyke mill, but no profits were coming in.

In July 1902, investors learned that Klondyke Mill still hadn't processed any ore. But Francis kept promising a bright future. Production finally started later that year. Work also began on new underground sections at Pandora.

The company employed about 100 men each year, which increased to 150. But the company had huge debts. Ore prices had dropped, and the large amounts of ore they expected weren't making the profits they hoped for. Pandora mine had been developed a lot on the surface, but not much underground.

In 1903, the Chairman, Edmund Pontifex, explained that delays at Klondyke Mill prevented them from testing the ore left by previous owners. He said they had to abandon those areas and dig into new ground.

The company's loans were much higher than expected. The mines had been bought for only £4,950, but over £27,791 had been spent on them since.

The situation didn't get better. Pandora mine never made a profit, even after spending about £70,000. The Welsh Crown Spelter Company went out of business in January 1905.

Klondyke Mill continued to operate on a smaller scale until it closed in 1911. The North Western Spelter Syndicate bought Pandora and Klondyke in 1906. They produced some lead and zinc ore, but their funding ran out after a year.

In June 1907, an advertisement appeared in a mining newspaper. It was selling many of the Welsh Crown Spelter Company's machines and equipment. This included railway tracks, a petrol train, wagons, and a cableway. It also listed mill equipment like a stone breaker, jigs, pulleys, and tools. The list showed that the mill relied heavily on electricity. Problems with the electrical pumping equipment might have also caused its decline.

A colliery owner from Liverpool bought everything at the auction. He formed the New Pandora Mining Syndicate Ltd. in 1908. About 50 men worked there, but the company closed in 1912. Another company, Hafna Mines Ltd., bought Pandora mine that year. However, they didn't buy Klondyke Mill because they had other places to process ore.

In 1919, an engineer named Edward McCarthy listed reasons why the Welsh Crown Spelter Company failed:

- They spent too much money on surface buildings and not enough on digging underground.

- They focused too much on a part of the mine that didn't have much ore.

- It was too expensive to get the right to build the tramway to the mill.

- The main tunnel (adit) wasn't ready until after the company left.

- The low prices of lead and zinc made it impossible to make a profit.

The Klondyke Scam

The mill is now known as Klondyke Mill because of a famous trick that happened there in the 1920s. The name comes from the Klondike Gold Rush, a time when many people rushed to find gold.

In 1918, a man named Joseph Aspinall, who had been in trouble with the law before, bought the mining rights from another company. In 1920, a mining newspaper reported that Aspinall's company had found a rich vein of silver in the Trefriw mines. The article claimed the mill machinery was modern and could process a lot of ore. But by 1920, Aspinall was in prison for running a scam.

Much of the story comes from Charles Holmes, who owned a nearby mine and helped expose the scam. Aspinall made unbelievable claims about how much ore the mine could produce. He hired many local men to help with his trick. He used the mill building and the mine entrance, even though the mine only had a couple of short tunnels with no minerals.

Aspinall would invite potential investors from London. He paid for their train tickets and hotels. Then, he would take them to see the mine and mill. As they approached the mine, he would honk his car horn. This was a secret signal for his "workers" to start their act.

The entrance tunnel to the mine had been cleaned. Aspinall had glued about 20 tons of lead ore (which he had shipped from another place) to the walls. This made the tunnel sparkle as if it were full of valuable minerals. He also bought galena (lead ore) locally, paying much more than the usual price. He claimed it was for a new secret process, but it was actually used to pretend he had mined ore. Men guarded the tunnel entrance, and others ran around, making it look like there was a lot of busy work happening.

Inside Klondyke Mill, most of the equipment was old and not very useful. But Aspinall installed a shaking table and set up a chute from the stone-breaker to it. With a few other machines, it all looked real and made convincing noises.

Charles Holmes became suspicious and told the police. Aspinall was eventually sent to prison for 22 months. He had tricked people out of about £166,000. After he was released, he moved to France and tried a similar scam, which led to 5 years in jail. In 1927, he received another 4 years for an oilfield scam.

The Site Today

Today, Klondyke Mill is quite dangerous and falling apart. The roof collapsed a long time ago. Recently, a small part of the east wall of the turbine house fell down. However, the rest of the building seems fairly stable because of its strong buttressed walls.

To the northwest of the mill, you can still see the remains of buddle pits. These were stone-lined pits used to clean and concentrate the lead ore. Further away, towards Crafnant road, are the remains of buddle ponds. These were reservoirs that stored water. You can legally access the site from Crafnant road along a public path. You can also get there from a path from Trefriw, which follows the old access road.

The waste heaps of shiny slag on the west side of the main building are still full of lead. Even after a hundred years, nothing grows on them.

The main mine tunnel (adit) was blocked with a metal grill in 2009 for safety. Inside, one of the main Klondyke tunnels is blocked by a concrete wall. It's thought this was done to use the tunnel as a pit for waste.

You can still see the route of the old tramway from Pandora mine. It runs down a hill on an embankment. It crosses the road and then follows the shore of Llyn Geirionydd. North of the lake, the tramway route is a flat path. It's now a public right of way and part of Trefriw trail No. 5. On the hillside above the mill, you can see small remains of the loading platform, water tank, and pipeline. From here, you can see where the aerial ropeway went steeply down to Klondyke Mill.

The Geirionydd gorge, with its old mine tunnels, is now a popular place for gorge walking (a type of outdoor activity).

Images for kids

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |