Levi Hill facts for kids

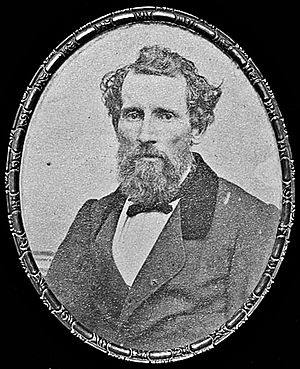

Levi Hill (born February 26, 1816 – died February 9, 1865) was an American minister who lived in upstate New York. In 1851, he announced that he had invented a way to take color photographs. He named his special process "heliochromy," and the pictures he made were called "heliochromes." However, people soon started calling his color photos "Hillotypes," much like the "daguerreotype" process was named after its inventor, Louis Daguerre. Many people doubted Hill's claims during his lifetime. For over a hundred years after he died, most photography historians believed his invention was a trick. But later on, researchers discovered that his very difficult process could actually show some colors from real life.

His Life and Discoveries

Levi Hill was a Baptist minister in a place called Westkill, located in the Catskill Mountains of New York.

In the early 1840s, Hill learned about the daguerreotype process. This was the most common way to take pictures back then. Daguerreotypes produced black-and-white photos, showing light and shadow but no color. By 1851, Hill had developed his own unique version of this process. He claimed his method could also capture the colors of whatever he was photographing. Many thought the colors in Hill's pictures were just added by hand. However, some scientists, like Samuel F. B. Morse (who invented the telegraph), supported him.

Hill's claims about his secret color photography process caused a lot of debate. Professional photographers were upset because they thought customers might wait for color "Hillotypes" instead of getting their pictures taken in black and white. In 1851, a group of photographers investigated Hill's invention. They decided it was "a delusion," meaning they thought it was not real.

In 1856, Hill wrote a book called A Treatise on Heliochromy. He promised this book would finally reveal his secret methods. It cost $25, which was a very high price at that time. A few copies of the book still exist today. They show that the book included parts of his life story, a history of photography, and many other photo recipes. But the instructions for making Hillotypes were so complex that they were almost impossible to follow.

Hill passed away in 1865 when he was 48 years old. It's thought that his death might have been caused by working with many dangerous chemicals during his experiments.

Uncovering the Truth About Hillotypes

In 1981, a photography professor and historian named Joseph Boudreau tried to recreate Hill's methods. He used the old chemical recipes and techniques described in Hill's book. Boudreau was able to make Hillotypes that clearly showed muted versions of many colors. These included red, green, blue, yellow, magenta, and orange. These colors were made by light alone, without any added dyes or paints.

Later, in 2007, scientists from the National Museum of American History did a chemical analysis of Hill's original photo plates. They found that some pigments (colors) had indeed been added by hand to make the pictures look more colorful. However, this was only true for some of the photographs. They discovered that reds and blues were mostly reproduced by the photographic process itself, even if they looked a bit rough. Other colors, though, had been added later. A scientist named Dusan Stulik, who helped with the analysis, said that Hill likely started adding extra colors by hand when people pressured him to show more colors in his photos.