Lithosphere facts for kids

The lithosphere is the Earth's strong, rocky outer layer. Think of it as our planet's hard shell.

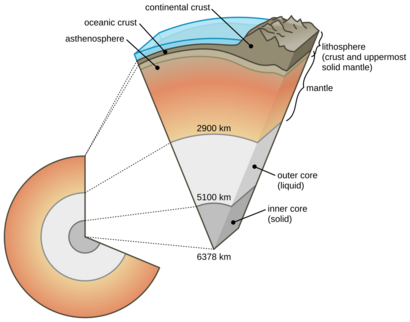

On Earth, the lithosphere includes the crust, which is what we walk on, and the very top part of the mantle. This top mantle layer is called the lithospheric mantle. Together, these parts act like a solid, rigid layer.

The lithosphere's total thickness varies, from as little as 5 kilometers (3 miles) under mid-ocean ridges to as much as 200 kilometers (124 miles) under older parts of continents. On average, it's about 100 kilometers (62 miles) thick.

Scientists tell the crust and the upper mantle apart by looking at their different chemicals and minerals. This rocky shell is very important because it's where plate tectonics happens.

Contents

What is the Lithosphere?

Earth's lithosphere is the tough, solid outer layer of our planet. It includes the crust and the top part of the mantle. This part of the mantle is called the lithospheric mantle. Unlike the deeper mantle, it doesn't flow or mix much.

Below the lithosphere is a layer called the asthenosphere. This layer is hotter and weaker. It can slowly flow, like very thick syrup. The difference between the rigid lithosphere and the flowing asthenosphere is key.

The lithosphere stays stiff for millions of years. It can bend a little or break. But the asthenosphere can slowly change shape. This difference helps us understand how plate tectonics works.

Scientists figure out the lithosphere's thickness by finding where rocks change. This is where they go from being stiff to being able to flow. A mineral called olivine becomes soft around 1,000 degrees Celsius. This temperature often marks the bottom of the lithosphere.

The lithosphere isn't one solid piece. It's broken into many large sections. These sections are called tectonic plates. These plates are always moving, though very slowly.

How We Learned About the Lithosphere

The idea of the lithosphere as Earth's strong outer layer started a long time ago. An English mathematician named A. E. H. Love first described it in 1911. Later, an American geologist, Joseph Barrell, developed the idea more. He also gave it the name "lithosphere."

Barrell noticed strange gravity patterns over the continents. He thought there must be a strong, solid layer on top. This layer, the lithosphere, would sit above a weaker, flowing layer. He called this weaker layer the asthenosphere.

These ideas were further explored by Canadian geologist Reginald Aldworth Daly in 1940. Today, most scientists agree with these concepts. Understanding the strong lithosphere and the flowing asthenosphere is key to understanding plate tectonics.

Two Main Types of Lithosphere

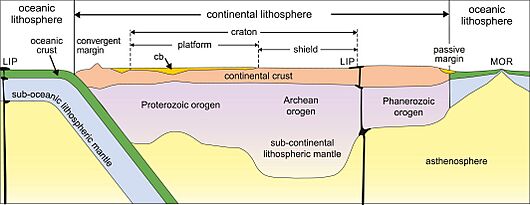

The lithosphere comes in two main types: oceanic and continental. Each type is found in different places on Earth. They also have slightly different features.

Oceanic Lithosphere

Oceanic lithosphere is found under the ocean basins. It is made mostly of a type of rock called mafic crust and a very dense rock called peridotite. This makes it heavier than continental lithosphere.

When oceanic lithosphere is new, near mid-ocean ridges, it's quite thin. But as it gets older and moves away from these ridges, it gets thicker. The oldest oceanic lithosphere can be about 140 kilometers thick. This happens as it cools down and more of the mantle becomes part of the rigid lithosphere.

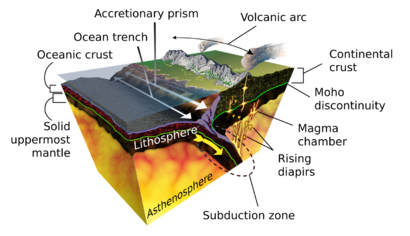

Oceanic lithosphere is always being made at mid-ocean ridges. It is also constantly being recycled back into the mantle. This happens at places called subduction zones. Because of this, oceanic lithosphere is much younger than continental lithosphere. The oldest parts are about 170 million years old.

Sinking Lithosphere

Scientists have studied how oceanic lithosphere sinks. They found that large pieces can go very deep into the mantle. Some even reach near the Earth's core. This sinking process is called subduction.

When oceanic lithosphere sinks, it stays rigid for a long time. We know this because deep earthquakes happen within it. These earthquakes can occur up to about 600 kilometers deep.

Continental Lithosphere

Continental lithosphere is found under the continents and continental shelves. It varies in thickness, from about 40 kilometers to as much as 280 kilometers. The top 30 to 50 kilometers of this is the continental crust.

The crust is separated from the upper mantle by a boundary called the Moho discontinuity. The oldest parts of the continents are called cratons. The lithosphere under these cratons is extra thick and less dense. This lower density helps these ancient regions stay stable.

Because continental lithosphere is lighter, it doesn't sink easily. When it reaches a subduction zone, it usually can't go much deeper than about 100 kilometers. Instead of sinking, it often gets pushed up or folded. This means continental lithosphere is not recycled like oceanic lithosphere. It is a very long-lasting part of Earth. Some parts are billions of years old.

Clues from Deep Rocks

Scientists can learn about the mantle by studying special rocks. These rocks are called xenoliths. They are pieces of the mantle brought to the surface by volcanic pipes. These pipes are like natural elevators from deep underground.

By studying these xenoliths, scientists can learn about the mantle's history. They look at tiny details, like different types of osmium and rhenium atoms. These studies have shown that the mantle under some ancient continental areas, called cratons, has been there for over 3 billion years. This is amazing, especially since the mantle is always slowly flowing.

Plate Tectonics

One of the most fascinating things about the lithosphere is that it's not one solid, unbroken shell. Instead, it's broken into several enormous pieces called tectonic plates. Imagine a giant jigsaw puzzle covering the entire Earth! These plates are constantly, though very slowly, moving across the Earth's surface.

These plates "float" on a semi-fluid layer beneath them called the asthenosphere, which is part of the mantle. Heat from Earth's core creates convection currents in the asthenosphere, slowly pushing and pulling the plates.

When these plates interact, incredible things happen:

- Collisions: When two continental plates collide, they can crumple and push upwards, forming massive mountain ranges like the Himalayas. When an oceanic plate collides with a continental plate, the denser oceanic plate often slides beneath the continental plate in a process called subduction, leading to volcanoes and deep ocean trenches.

- Separation: When plates pull apart, magma (molten rock) from the mantle rises to fill the gap, creating new oceanic crust, often seen at mid-ocean ridges.

- Sliding Past Each Other: When plates slide horizontally past each other, immense stress can build up and be suddenly released, causing earthquakes.

The movement of these plates, along with other geological processes, creates all the major landforms we see:

- Mountains: Formed by plate collisions or volcanic activity.

- Valleys and Canyons: Often carved by rivers or glaciers, or formed by fault lines.

- Ocean Basins: Vast depressions filled with water, created by the spreading of oceanic plates.

- Volcanoes: Openings in the Earth's crust where molten rock, ash, and gases erupt.

- Earthquakes: Sudden shaking of the ground caused by the movement of tectonic plates.

Tiny Life Deep Down

The upper part of the lithosphere is home to many tiny living things. These are microorganisms, like bacteria. Some have been found more than 5 kilometers (about 3 miles) below Earth's surface. This shows that life can exist in very extreme places!

Importance of the Lithosphere

- The lithosphere provides the solid ground for all terrestrial life – plants, animals, and humans.

- It's the source of vital natural resources like minerals (iron, copper, gold), fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas), and geothermal energy.

- It's the stable foundation upon which our cities, roads, and infrastructure are built.

- The lithosphere drives geological processes that shape the planet's surface over millions of years.

Intersting Facts About the Lithosphere

- Origin of the name:The word "lithosphere" comes from Greek words meaning "rocky" and "sphere."

- Average thickness: Approximately 100 km (62 miles).

- Major Tectonic Plates: There are about 7-8 major plates (e.g., African, Pacific, North American) and many smaller ones.

- Plate Movement Speed: Plates move at speeds ranging from 0.6 cm (0.24 inches) to 10 cm (4 inches) per year – about as fast as your fingernails grow!

- Highest Point: Mount Everest, 8,848.86 meters (29,031.7 feet) above sea level.

- Deepest Point: Mariana Trench, about 11,000 meters (36,000 feet) below sea level

Related pages

See also

In Spanish: Litosfera para niños

In Spanish: Litosfera para niños

- Carbonate–silicate cycle

- Climate system

- Cryosphere

- Geosphere

- Kola Superdeep Borehole

- Mohorovičić discontinuity

- Pedosphere

- Solid earth

- Vertical displacement

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |