London Beer Flood facts for kids

The London Beer Flood was a strange accident that happened at the Meux & Co brewery in London on 17 October 1814. It all started when a huge wooden barrel, about 22 feet (6.7 meters) tall, filled with fermenting beer called porter, suddenly burst.

This powerful burst caused a chain reaction. The gushing beer knocked loose the valve of another large barrel and destroyed several smaller ones. In total, between 128,000 and 323,000 imperial gallons (580,000–1,470,000 liters) of beer flooded out!

The massive wave of beer crashed through the back wall of the brewery. It then swept into a nearby area of poor homes called the St Giles rookery. Sadly, eight people lost their lives. Five of them were attending a wake (a gathering for a deceased person) for a two-year-old boy. An official investigation later ruled that the deaths were "casually, accidentally and by misfortune," meaning they were an accident.

The brewery almost went out of business because of the disaster. However, they were saved when the government gave them a tax refund for the lost beer. After this event, breweries slowly stopped using such giant wooden barrels. The Meux & Co brewery moved in 1921, and today, the Dominion Theatre stands where the brewery once was.

Contents

About the Brewery and Area

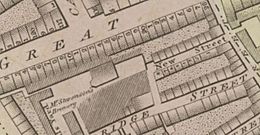

In the early 1800s, Meux Brewery was one of London's biggest breweries. In 1809, Sir Henry Meux bought the Horse Shoe Brewery. It was located at the corner of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street. Henry Meux followed his father's example and built a huge wooden barrel. This barrel was 22 feet (6.7 meters) tall and could hold 18,000 imperial barrels of beer. Heavy iron bands were used to make the barrel stronger.

Meux & Co only brewed a dark beer called porter. Porter was first made in London and was the most popular alcoholic drink in the city. The brewery made a lot of it, over 100,000 imperial barrels in one year! This beer was left in the large barrels to age for several months, sometimes even a year, to get the best quality.

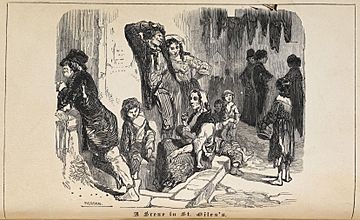

Behind the brewery was a small street called New Street. This street was part of the St Giles rookery. A rookery was a very crowded and poor area. One writer described the St Giles rookery as "a meeting place for the worst parts of society."

The Day of the Flood: 17 October 1814

Around 4:30 in the afternoon on 17 October 1814, George Crick, a worker at the brewery, noticed something. One of the heavy iron bands around a large beer barrel had slipped. This barrel was 22 feet (6.7 meters) tall and almost full with 3,555 imperial barrels of porter that had been aging for ten months.

Crick wasn't too worried because these bands slipped a few times a year. He told his boss, who said "no harm whatever would ensue." Crick was told to write a note to one of the brewery owners, Mr. Young, to have it fixed later.

About an hour after the band slipped, Crick was standing on a platform near the barrel. Suddenly, without any warning, the huge barrel burst open! The force of the beer rushing out was so strong that it knocked the tap off a nearby barrel, which also started emptying its contents. Several other large barrels were destroyed, adding to the flood. In total, between 128,000 and 323,000 imperial gallons of beer were released.

The powerful wave of liquid destroyed the brewery's back wall. This wall was 25 feet (7.6 meters) high and very thick. Some of its bricks were thrown upwards and landed on the roofs of houses on a nearby street.

A wave of porter, about 15 feet (4.6 meters) high, rushed into New Street. It destroyed two houses and badly damaged two others. In one house, a four-year-old girl named Hannah Bamfield was having tea with her mother. The wave of beer swept her mother and another child into the street, but Hannah was killed.

In the second destroyed house, an Irish family was holding a wake for a two-year-old boy. Anne Saville, the boy's mother, and four other people (Mary Mulvey, her three-year-old son Thomas Murry, Elizabeth Smith, and Catherine Butler) were killed. Eleanor Cooper, a 14-year-old servant, died when she was buried under the brewery's collapsed wall while washing pots in a pub yard. Another child, Sarah Bates, was found dead in a different house on New Street.

The area around the brewery was low and flat, and there wasn't enough drainage. So, the beer flowed into cellars, where many people lived. People had to climb onto furniture to avoid drowning. Luckily, everyone inside the brewery survived, though three workers had to be rescued from the rubble.

After the Flood

The area behind the brewery looked like a disaster zone, "equal to that which fire or earthquake may be supposed to occasion." Watchmen at the brewery charged people money to see the remains of the destroyed beer barrels. Hundreds of people came to look at the scene.

The people killed in the cellar had their own wake at a nearby pub. The other bodies were laid out in a yard by their families. People came to see them and donated money to help pay for their funerals. Collections were also taken up more widely to help the families affected by the flood.

Official Investigation

An official investigation, called a coroner's inquest, was held on 19 October 1814. It took place at the workhouse of the St Giles parish. The coroner, George Hodgson, led the proceedings. The names and ages of the eight victims were read out:

- Eleanor Cooper, age 14

- Mary Mulvey, age 30

- Thomas Murry, age 3 (Mary Mulvey's son)

- Hannah Bamfield, age 4 years 4 months

- Sarah Bates, age 3 years 5 months

- Ann Saville, age 60

- Elizabeth Smith, age 27

- Catherine Butler, age 65

The jury went to see the brewery and the bodies before hearing from witnesses. George Crick, who saw the barrel burst, was the first witness. He explained that the barrel hoops failed a few times a year, but nothing like this had ever happened before. Other people, including the landlord of a pub where one victim worked, also gave their accounts. The jury decided that the eight people died "casually, accidentally and by misfortune." This meant it was a pure accident.

What Happened Next

Because the investigation ruled the event an "act of God" (meaning an unavoidable accident), Meux & Co brewery did not have to pay money to the victims' families. However, the disaster still cost the company a lot of money. They lost the beer, their buildings were damaged, and they had to replace the huge barrel. This cost them about £23,000 (which would be millions in today's money). After asking the government for help, they got back about £7,250 in taxes, which saved them from going bankrupt.

The Horse Shoe Brewery started making beer again soon after the flood. But it closed in 1921 when Meux moved its production to another brewery. The old brewery site was torn down the next year, and the Dominion Theatre was built there later. Meux & Co eventually closed down completely in 1961.

As a result of this terrible accident, breweries across the industry gradually stopped using such enormous wooden tanks. They started using concrete tanks instead, which were much safer.

See also

- List of non-water floods

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |