St Giles in the Fields facts for kids

Quick facts for kids St Giles in the Fields |

|

|---|---|

Church of St Giles-in-the-Fields, London

|

|

| Location | St Giles High Street, London, WC2H 8LG |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | Traditional Anglican Book of Common Prayer |

| Website | www.stgilesonline.org |

| History | |

| Founded | 1101 |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Architect(s) | Henry Flitcroft |

| Style | Palladian |

| Years built | 1731-33 |

| Administration | |

| Deanery | Westminster (St Margaret) |

| Archdeaconry | London |

| Diocese | Diocese of London |

St Giles in the Fields is an Anglican church in the St Giles area of London. It is part of the Church of England and the Diocese of London. The church is named after St Giles the Hermit. It started as a small chapel for a monastery and a hospital for people with leprosy in the 12th century.

The church was built in the fields between Westminster and the City of London. Today, it gives its name to the busy area of St Giles in the West End. This area is near Seven Dials, Bloomsbury, Holborn, and Soho. The building you see today is the third church on this spot since 1101. It was rebuilt between 1731 and 1733 in a Palladian style. The architect was Henry Flitcroft.

Contents

- History of St Giles Church

- St Giles Churchyard

- Interesting Features of St Giles

- Life at St Giles Church Today

- Rectors of St Giles from 1547

History of St Giles Church

Early Beginnings: 12th to 16th Centuries

A Hospital and Its Chapel

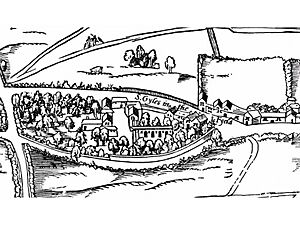

The first church here was a chapel. It was part of a monastery and a hospital for people with leprosy. Matilda of Scotland, Queen of Henry I, founded it between 1101 and 1109. At that time, it was outside the City of London. It stood on the main road leading to Tyburn and Oxford.

Later, Henry II gave the hospital land and gifts. This helped it grow and become secure. The chapel likely became the church for a small village that grew around the hospital. Records show that St Giles parish existed by 1222. This means the church was used by local people from then on.

The hospital area was quite large. It included the land where the church stands today. There were also other buildings, like the Master's House. The 'Spittle Houses' were homes for people connected to the hospital. The Angel Inn, which is still there, was also part of this area.

It's interesting that St Giles was built between Westminster and London. Many old English towns had a St Giles church outside their walls. This was because lepers were often kept outside the main settlements.

Managed by the Lazar Brothers

In the 13th century, the Pope gave the hospital special protection. This meant it was directly under the Pope's authority. The hospital had gardens and 8 acres of land. The King and the City of London supported it for 200 years.

In 1299, Edward I gave the hospital to the Lazar Brothers. This was a special group from the Crusades. The 14th century was a tough time for the hospital. There were many complaints about how it was managed. People said the Lazar brothers cared more about their order than the sick.

In 1348, people complained to the King. They said the friars had replaced the lepers with healthy brothers and sisters. The King stepped in and appointed new leaders.

In 1391, Richard II sold the hospital and its land. It went to the Cistercian abbey of Eastminster. But the Lazar brothers fought back. They even used armed men to take St Giles back. The City of London also protested by not paying rent. The dispute ended peacefully in court. The King admitted he was wrong and returned the property to the Lazar Brothers.

The property included 8 acres of farmland. It also had many animals like horses, oxen, pigs, and geese. Lepers were cared for here until the mid-1500s. After that, the hospital started caring for poor people instead. The hospital area was entered through a gatehouse on St Giles High Street.

The Lollard Uprising

In 1414, the fields around St Giles were important. Sir John Oldcastle led a group called the Lollards there. They were early Protestants who disagreed with the Catholic Church. They also had ideas about how the government should work.

The Lollards planned to meet in the 'dark thickets' near St Giles's Fields. This was on the night of January 9, 1414. But King Henry V knew about their plan. His agents warned him. The small group of Lollards were captured or scattered. This rebellion led to harsh punishments. Many rebels were executed. This event ended the Lollards' open political power.

The poet Lord Tennyson wrote about this event. His poem Sir John Oldcastle, Lord Cobham describes the Lollards meeting in the fields.

16th Century: Changes and Challenges

The Hospital Closes and a New Church Appears

During the reign of King Henry VIII, the hospital lost most of its land. This happened in 1536. Then, in 1544, the entire hospital was closed down. All its lands and rights were given to John Dudley.

However, the chapel survived. It became the local parish church. In 1547, the first Rector of St Giles was appointed. The phrase "in the fields" was added to its name. This helped tell it apart from St Giles Cripplegate.

We don't have much left of the medieval church. But we can imagine what it looked like. Records from 1623 say it was 153 feet long and 65 feet wide. It had a main area (nave) and a special area for the altar (chancel). Both had pillars and windows high up. There were also aisles on each side.

It seems the church had three parts. It likely had side aisles with rounded arches. Light came in through high windows. These led to chapels for St Michael and St Giles. A screen probably separated the main part from the altar area.

A record from 1617 suggests there was a round tower or spire at the west end. The 12th-century Church of St James in Burton Lazars, Leicestershire, looks similar. It was also part of the Order of St Lazarus.

The Babington Plot

About 140 years after the Lollard uprising, St Giles was involved in another event. This was the Babington Plot. In 1570, the Pope had allowed English Catholics to try and overthrow the Protestant Queen.

In 1585, a group of Catholics and Jesuit priests met near St Giles. They planned to kill Queen Elizabeth I. They also wanted to invite Spain to invade England. Their goal was to replace Elizabeth with the Catholic Queen Mary.

The main plotters were Anthony Babington and John Ballard. Ballard was a Jesuit priest. He hoped to get rid of Queen Elizabeth and free Queen Mary.

Queen Elizabeth's spy master, Francis Walsingham, quickly found out about the plot. He used it to trap Mary. The plans were made in talks held in St Giles's Fields and local taverns. When the plot was exposed, the plotters were brought back to St Giles churchyard. They were executed there.

Ballard and Babington were executed on September 20, 1586. Mary, Queen of Scots, was also executed in 1587. This was because she had approved the plot. This event made people in England even more against Catholics.

17th Century: War, Restoration, and Plague

Duchess Dudley's Church

By the early 1600s, the medieval church was falling apart. So, the local people decided to build a new one. Construction started in 1623 and finished in 1630. It was officially opened on January 26, 1630. Most of the money came from Duchess Dudley. Even the 'poor players' from The Cockpit theatre gave £20.

The new church was beautifully decorated. It was 123 feet long and 57 feet wide. It had a brick steeple and galleries on the sides. A large stained-glass window was at the east end.

William Laud, the Bishop of London, opened the new building. A list of everyone who donated money is still kept in the church.

Civil War and Religious Conflict

Problems between the church and state started early in St Giles parish. These problems eventually led to the Civil War. In 1628, the first rector, Roger Maynwaring, was punished. He had given two sermons that Parliament thought were against their rights. He had also supported the idea that kings had a Divine Right to rule.

The arguments continued into the 1630s. Archbishop Laud's former chaplain, William Heywood, became Rector. Heywood started adding many decorations to St Giles. He also changed how services were done. This made the Protestant (especially Puritan) church members angry.

They complained to Parliament. They listed the 'popish reliques' (Catholic-style items) Heywood had added. They also described the 'Superstitious and Idolatrous manner' of the services. For example, they said the clergy would move around a lot and make strange actions with their hands.

The church was heavily decorated by Heywood. It had a fancy screen of carved oak. This screen had two large pillars and three statues: Paul, Barnabas, and Peter. It also had winged cherubs and lions. Expensive altar rails separated the altar from the people.

Because of the complaints, most of these decorations were removed and sold in 1643.

Dr Heywood was still the rector when the Civil War began in 1642. He was also a chaplain to Archbishop Laud and King Charles I. After the King was executed, Heywood was imprisoned. He suffered many difficulties. He had to leave London. But after the monarchy was restored in 1660, he returned to St Giles.

In 1645, a copy of the Solemn League and Covenant was put in the church. In 1650, after the King's execution, the 'Kings Arms' were removed from the church. The windows were also changed to clear glass.

After the King returned in 1660, the bells of St Giles rang for three days. William Heywood was briefly reinstated. Then Robert Boreman became rector. He was a Royalist who had also suffered. Boreman is known for his arguments with Richard Baxter, a Nonconformist leader.

Rector John Sharp and the Glorious Revolution

In 1675, Dr. John Sharp became the Rector. He was supported by Heneage Finch, 1st Earl of Nottingham. Sharp's father was a Puritan, but his mother was a Royalist. So, he understood both sides of the reformed religion in England.

Sharp loved his work at St Giles. He even turned down a better job at St Martin-in-the-Fields. He wanted to keep helping the poor people of St Giles.

For the next 16 years, Sharp worked to improve the parish. He preached regularly, often twice on Sundays. He was known as a very popular preacher. Sharp completely reorganized the church services. He used the Book of Common Prayer, which he thought was "almost perfectly designed." He started weekly Holy Communion services. He also brought back daily prayers. Sharp insisted that people kneel to receive communion.

He also taught young people about their faith. He visited the sick, even when it was dangerous. He avoided getting sick himself, even though the area was known for plague. Once, he survived an attempt on his life. Someone tried to trick him into visiting a "dying parishioner."

In 1685, Sharp helped write a message to King James II. He congratulated the King on becoming ruler. In 1686, he became a chaplain to the King. However, Sharp was worried about Jesuit priests trying to change his parishioners' faith. He preached two sermons in May that criticized the King's religious policies.

As a result, Henry Compton, bishop of London, was told to remove Sharp from St Giles. Compton refused. But he advised Sharp to stop preaching for a while. Sharp left London. But in January 1687, he was reinstated.

In August 1688, Sharp had more trouble. He refused to read the declaration of indulgence. He was called before the King's commission. He argued that he should obey the King, but only if it was legal and honest.

After the Glorious Revolution, Sharp visited 'Bloody' Jeffreys in the Tower of London. He tried to help him feel sorry for his crimes. Soon after the Revolution, Sharp preached before Prince of Orange (who became King William III). He also preached before Parliament. He still prayed for King James II. In 1689, he became dean of Canterbury. He became Archbishop of York in 1691.

The Great Plague in St Giles

The Bubonic Plague had first appeared in London in 1348. It returned many times over the next 318 years. The outbreaks in 1362, 1369, 1471, and 1479 were very bad.

St Giles parish had the sad distinction of being where the last and worst plague started. This was the Great Plague of London between 1665 and 1666. Daniel Defoe wrote that the first people to get sick lived near Drury Lane. This was about 350 yards from St Giles church. Two Frenchmen staying with a family there caught the plague and died quickly.

By June 7, 1665, Samuel Pepys saw the terrible red Plague Cross painted on doors in St Giles parish. He wrote, "I did in Drury-lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and "Lord have mercy upon us" writ there - which was a sad sight to me, being the first of that kind that to my remembrance I ever saw."

By September 1665, 8,000 people were dying each week in London. By the end of the plague year, about 100,000 people had died. This was almost a quarter of London's population. In St Giles parish, 3,216 plague deaths were recorded. This was a huge number for a parish with fewer than 2,000 homes. The real number was likely higher. People often didn't report deaths to avoid quarantine.

18th–19th Centuries: Rebuilding and Growth

The Henry Flitcroft Church

Many plague victims were buried in and around the church. This caused a damp problem by 1711. The churchyard had risen about eight feet above the church floor. The people asked for money to rebuild the church.

They were first refused. But eventually, the parish received £8,000. This is about £1.2 million today. A new church was built from 1730 to 1734. It was designed by Henry Flitcroft in the Palladian style. The first stone was laid on September 29, 1731.

The Flitcroft rebuilding was a big change in church design. It was one of the first Palladian churches in London. Nicholas Hawksmoor was first considered to design the church. But people didn't like his style anymore. So, the young Henry Flitcroft was chosen. He was inspired by the buildings of Inigo Jones.

Flitcroft borrowed the idea for the spire from James Gibbs's St Martin-in-the-Fields. But he made it his own. A wooden model of his design can still be seen in the church. The Vestry House was also built at this time.

The Rookery

As London grew, so did the parish's population. By 1831, it reached 30,000 people. This meant the area was very crowded. It included two poor and dirty neighborhoods: the St Giles Rookery and Seven Dials. These areas became known for crime. The name St Giles became linked with the underworld.

St Giles's Roundhouse was a prison. "St Giles' Greek" was a term for thieves' language. As the population grew, so did the number of dead. There was no more room in the churchyard. Many people were buried outside the parish. This included the architect Sir John Soane.

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, sometimes preached at St Giles. He used a large pulpit from 1676. This pulpit is still used today. A smaller, whitewashed pulpit is also in the church. It came from the nearby West Street Chapel. Both John and Charles Wesley used it.

Charles Dickens described the area in his book Sketches by Boz. Architects Sir Arthur Blomfield and William Butterfield made small changes to the church inside in 1875 and 1896.

20th Century: War Damage and Repair

St Giles was not directly hit during the Second World War. But bombs still destroyed most of its stained glass. The roof of the main part of the church was badly damaged. The Vestry house was filled with rubble. The Rectory was completely destroyed.

The parish itself was in a bad state. Money was stolen. The war had scattered the church members. In 1949, Revd Gordon Taylor became Rector. He worked hard to rebuild the church and parish.

The church was named a Grade I listed building in 1951. Revd. Gordon Taylor raised money for a big restoration. This happened between 1952 and 1953. The work followed Flitcroft's original plans. The journalist John Betjeman praised it. He called it "one of the most successful post-war church restorations."

Revd. Gordon Taylor slowly rebuilt the church community. He also fixed the St Giles's Almshouses. He brought back the old charities that helped the poor. He also worked to stop a big road from being built through the parish. This road would have destroyed historic parts of London.

Later, Rev. Taylor saw St Giles as a protector of the Church of England's traditions. He kept using the Book of Common Prayer in the parish.

St Giles Churchyard

The churchyard is south of the church. It was the burial ground for the Leper Hospital. Even though it's small, it holds thousands of bodies. They were buried on top of each other over centuries. The churchyard was made bigger many times. But overcrowding was always a problem. In 1628, a piece of land called Brown's Gardens was added.

The churchyard often looked run down. The way poor people were buried was not always respectful. In 1803, a new burial ground was bought. It was two miles away, next to St. Pancras Old Church. Sir John Soane is buried there. This area is now called St. Pancras Gardens.

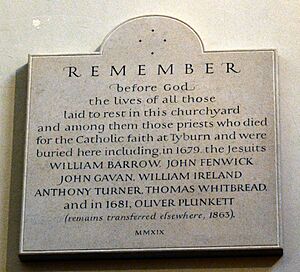

Catholic Burials at St Giles

The churchyard of St Giles is special to Roman Catholics. Some have called it "London's most Hallowed Space." The ground was originally blessed by the Roman church. It was later protected by Pope Alexander IV. So, it was considered a good place for Catholics to be buried. This was especially true during times when Catholics faced harsh laws in England.

Many important Catholics were buried here after the Reformation. Also, thousands of poor Irish Catholic immigrants were buried here. During the religious conflicts of the 17th century, several notable Catholics were buried here. These included John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse, Richard Penderel, and James Radclyffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater. Radcliffe was executed after the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715.

The St Giles 'Martyrs'

Several Catholic priests and laymen were executed for treason. This happened during the false conspiracy known as the Popish Plot. They were buried near the church's north wall.

These included:

- Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh. He was buried on July 1, 1681. But his body was later moved to Germany. His head went to Rome and is now in Drogheda. His body rests at Downside Abbey.

- The five Jesuit fathers Plunkett wanted to be buried with:

* Thomas Whitbread * William Harcourt * John Fenwick * John Gavan * Anthony Turner (martyr)

- Edward Coleman, secretary to the Duchess of York.

- Richard Langhorne, a lawyer.

- Edward Micó, a priest who died soon after arrest.

- William Ireland.

- John Grove, a priest.

- Thomas Pickering, a lay brother.

All 12 were later declared "Blessed" by Pope Pius XI. Oliver Plunkett was made a saint by Pope Paul VI in 1975. A memorial for the seven Jesuits and others buried in the churchyard was unveiled in 2019.

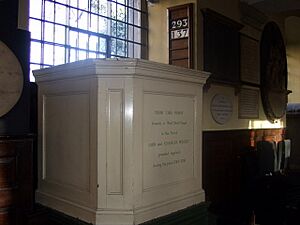

Richard Penderel's Tomb

Not many old tombs are still in the St Giles Churchyard. But among the bushes at the east end of the church is the tomb of Richard Penderel. He was a humble farmer who helped King Charles II escape. This happened after the Battle of Worcester in 1651.

Penderel hid the King in his home. He then helped him hide in the branches of the Royal Oak tree. This was to avoid those who were chasing him. Penderel and his five brothers later helped the King start his dangerous escape to France.

After the King returned to power, Penderel received a good pension. He visited the King's court once a year. In 1671–72, he caught the "St Giles Fever" and died. He was buried under a grand tomb. The tomb was repaired by order of George II in 1739. But it later fell apart again.

The words on the side of the tomb are still faintly visible. They tell the story of Richard Pendrell. In 1922, the tomb slab was moved inside the church. It is now next to the memorial for John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse.

The Resurrection Gate

At the west end of the churchyard is the Resurrection Gate. It's a grand gate with Doric columns. It used to be on the north side of the churchyard. Condemned prisoners would pass through it on their way to be executed at Tyburn.

The Gate has a carving of the Day of Judgement. This carving was probably made by a wood-carver named Mr Love. It was ordered in 1686.

The Gate was rebuilt in 1810. This was based on designs by William Leverton. In 1865, it was moved to face the west door. This was because Charing Cross Road was going to be built. But the road bypassed Flitcroft Street. Now the gate faces a narrow alleyway.

Interesting Features of St Giles

The "Poets' Church"

St Giles has recently been called the "Poets' Church." This is because of its links to many poets, playwrights, actors, and translators. These connections started in the 16th century. The second church building was partly paid for by actors from the Cockpit Theatre.

An early rector, Nathaniel Baxter, was both a clergyman and a poet. He was a tutor to Sir Philip Sidney. He is known for his long poem, Ourania.

Another poet buried at St Giles is Edward Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Cherbury (died 1648). He was the brother of the poet George Herbert. Edward published a controversial book called De Veritate. His poetry is admired. He is thought to have inspired Tennyson's poem In Memoriam.

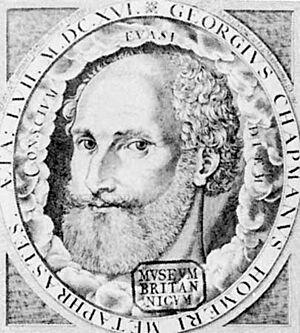

George Chapman

A stone memorial in the north aisle honors George Chapman (1559 – 1634). He was a great English dramatist, translator, and poet. Chapman was a expert in classical languages. He published the first complete English translation of Homer's works. This was the most popular English version for a long time.

Chapman also translated other famous works. These included the Homeric Hymns and parts of Virgil and Hesiod. He mainly wrote plays, including comedies and tragedies. He also worked with John Marston and Ben Jonson on the comedy Eastward Ho!. This play got him sent to prison for insulting the King's Scottish friends.

Chapman is also famous because of John Keats's sonnet 'On First Looking into Chapman's Homer'. Some people think Chapman might be the "Rival Poet" in Shakespeare's Sonnets. Chapman's memorial was designed and paid for by Inigo Jones. Chapman died very poor.

James Shirley and the Stuart Stage

St Giles continued its connection with poetry and theatre. This was true even after Parliament closed the theatres. The connection revived when the monarchy was restored. James Shirley and Thomas Nabbes were playwrights. They wrote plays, comedies, and tragedies. Both had a long connection with the church and are buried in the churchyard.

Shirley was a very popular playwright during the reign of King Charles I. He wrote 31 plays. He was known for his comedies about London life. Today, he is perhaps best known for his poem 'Death the Leveller'. It begins:

The glories of our blood and state

Are shadows, not substantial things;

There is no armour against fate;

Death lays his icy hand on kings:

Sceptre and crown

Must tumble down,

And in the dust be equal made

With the poor crooked scythe and spade.

Michael Mohun, a leading English actor, is also buried here. He was famous for playing villains. He also played a role in a play written by his fellow St Giles parishioner, James Shirley.

Andrew Marvell

The politician, writer, and poet Andrew Marvell (died 1678) is buried and remembered in St Giles. Marvell was connected to St Giles in many ways. He wrote songs for the wedding of Mary Cromwell, Lord Protector's daughter. She married Thomas Belasyse. This marriage was meant to unite the country.

After the monarchy was restored, the Catholic Belasyse family gained power. John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse (also buried at St Giles) tried to remove Marvell from Parliament. Years later, Marvell wrote a pamphlet that contributed to anti-Catholic feelings. This led to John Belasyse being imprisoned in the Tower.

Belasyse spent five years in the Tower without a trial. This period was during the Popish Plot. It ended with the trial and execution of 12 Jesuits and Oliver Plunkett. They were all buried in St Giles Churchyard, near Marvell and Belasyse.

Sir Roger L'Estrange

The translator, writer, and last Surveyor of the Press in England, Sir Roger L' Estrange, is buried and remembered at St Giles. He was a national censor of books and newspapers until 1672. He was called the "Bloodhound of the Press." He controlled what was published.

L'Estrange stopped publications that he thought were rebellious. He also reduced public debates. Besides his official duties, L'Estrange translated works by Seneca the Younger and Cicero. He also wrote a guide to Hudibras, a satirical poem.

L'Estrange's most important work was the first English translation of Aesop's Fables for children. This might be one of the earliest children's books. It came out after John Locke's ideas about children's minds. Locke thought children should have "easy pleasant books" to help them learn.

L'Estrange is often remembered for trying to remove lines from John Milton's Paradise Lost. He thought they might insult the King.

As when the Sun new ris'n

Looks through the Horizontal misty Air

Shorn of his Beams, or from behind the Moon

In dim Eclips disastrous twilight sheds

On half the Nations, and with fear of change

Perplexes Monarchs

Even though he is sometimes seen as narrow-minded, he believed he was right. He also did not believe in the false Popish Plot.

The Romantics

John Milton's daughter Mary was baptized in the second church building in 1647. The daughter of Lord Byron, Clara, was baptized in the current St Giles church font. The children of the poet Percy Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin were also baptized there.

The Poetry Society holds its yearly meeting in St Giles Vestry House.

The St Giles Bowl

By the early 1400s, the main place for executions in London moved. It was moved to the northwest corner of the St Giles hospital wall. A gallows was set up there. It became a custom for the hospital to offer the condemned person a drink. This was a 'broad wooden bowl' of 'nutty brown ale'. It was meant to ease their journey to the next life. This drink became known as the 'St Giles Bowl'.

After the hospital closed, the custom continued. The churchwardens of St Giles kept it up. The execution site later moved to Tyburn.

In 1598, John Stow wrote about this custom. He said prisoners on their way to Tyburn were given a "great bowl of ale." They could drink as much as they wanted. It was their "last refreshing in this life." Walter Thornbury later noted that almost every execution recorded mentioned this stop.

The 'public house' was likely on the site of the current Angel Inn. It was sometimes called The Crown. The Angel Inn is mentioned when the hospital closed in 1539. In 1873, the City Press reported that the Angel Inn was about to be torn down. It was known as the "half-way house" to Tyburn. Criminals and their executioners would stop there for a "last glass."

Many famous criminals took the St Giles Bowl at the Angel. These included John Cottington and John Nevison. Perhaps the most famous scene involved the thief 'Honest Jack' Sheppard. He was on his way to Tyburn with 200,000 people watching. He refused the Bowl. Instead, he said his enemy, Jonathan Wild, would taste the cup within six months. Six months later, Wild was executed at Tyburn.

The novelist William Harrison Ainsworth wrote a song about the St Giles Cup. It begins:

"Where Saint Giles's Church stands, once a lazar-house stood;

And chained to its gates was a vessel of wood;

A broad-bottomed bowl, from which all the fine fellows,

Who passed by that spot on their way to the gallows,

Might tipple strong beer Their spirits to cheer,

And drown in a sea of good liquor all fear !

For nothing the transit to Tyburn beguiles

So well as a draught from the Bowl of Saint Giles !"

The Church Organ

The first organ in the 17th century was destroyed during the English Civil War. George Dallam built a new one in 1678. It was rebuilt in 1699 by Christian Smith. A second rebuilding happened in 1734. Much of the old pipes from 1678 and 1699 were reused.

In 1856, London organ builders Gray & Davison rebuilt it again. They reused many of Dallam's original pipes. In 1960, the organ's actions were changed to electro-pneumatic. This was removed during a big restoration in 2006. William Drake restored it to its original style. He kept as many old pipes as possible. New pipes were made in a 17th-century style.

Wesley's Pulpit

In the east end of the north aisle, there is a small box pulpit. Both John and Charles Wesley, leaders of the Methodist movement, preached from it.

It is now whitewashed and has a memorial. It is the top part of a 'triple decker' pulpit. Wesley would have used it in the nearby West Street Chapel. Wesley leased the building from a small Huguenot group. It stayed with the Methodists until his death in 1791.

George Whitfield and John William Fletcher also preached from this pulpit. In the early 1800s, the chapel became an Anglican church. It later closed for worship. The pulpit was then moved to St Giles for safekeeping.

The Baptismal Font

The white marble font dates from 1810. It has Greek Revival details. The expert Pevsner believes it was designed by Sir John Soane.

On March 9, 1818, William and Clara Everina Shelley were baptized here. Their mother, the novelist Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, and her husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, were present. Also baptized that day was Allegra. She was the daughter of Mary's step-sister Claire Clairmont and the poet Lord Byron. The group was in a hurry to baptize the children. They wanted to take Allegra to her father, Lord Byron, in Venice.

All three children died young in Italy. After Allegra Byron died at age 5, Shelley wrote about her. He described her as Count Maddalo's child in his 1819 poem Julian and Maddalo: A Conversation:

A lovelier toy sweet Nature never made;

A serious, subtle, wild, yet gentle being;

Graceful without design, and unforeseeing;

With eyes – O speak not of her eyes! which seem

Twin mirrors of Italian heaven, yet gleam

With such deep meaning as we never see

But in the human countenance.

Shelley himself never returned to England. He drowned off the coast of Leghorn in 1822.

Memorials at St Giles

Many important people have memorials in St Giles. These include:

- Richard Penderel: A Catholic farmer who helped King Charles II escape after the Battle of Worcester.

- John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse: A Royalist officer and Member of Parliament. He fought in many battles during the Civil War. He was also a founder of The Sealed Knot, a secret Royalist group.

- Sir Roger L'Estrange: An English writer and the last Surveyor of the Press in England.

- Andrew Marvell: An English metaphysical poet, satirist, and politician.

- John Flaxman RA: A famous sculptor and draughtsman. He was a leader in Neoclassicism.

- Luke Hansard: Printer to the House of Commons.

- Thomas Earnshaw: A watchmaker who made marine chronometers easier to produce. He was watchmaker to Captain William Bligh of the Bounty.

- Arthur William Devis: An English history painter. His most famous work is The Death of Nelson.

- James Shirley: A 17th-century English playwright.

- Thomas Nabbes: A 17th-century English playwright.

- Edward Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Cherbury: An Anglo-Welsh soldier, diplomat, historian, poet, and philosopher.

- George Chapman: An English dramatist, translator, and poet.

- Cecil Calvert: The first owner of the Colony of Avalon and the Maryland colony. His memorial was unveiled in 1996.

- William Balmain: One of the founders of New South Wales. He was the Principal Surgeon of the Colony. His memorial was put up in 1996.

- John Lumsden of Cushnie: A member of the Supreme Council of Bengal. He became a director of the East India Company.

- John Coleridge Patteson: Born in St Giles Parish. He became a missionary and anti-slavery campaigner. He was the first Anglican Bishop of Melanesia. He was killed on the island of Nukapu. He is remembered in the Church of England calendar on September 20.

HMS Indefatigable White Ensign

St Giles in the Fields keeps the White Ensign flag from HMS Indefatigable. This flag was flown when the Japanese surrendered in Tokyo Bay on September 5, 1945. HMS Indefatigable was the adopted ship of Metropolitan Borough of Holborn. In 1989, the flag was placed in St Giles. Members of the ship's crew from World War II were there.

St Giles and Homelessness

St Giles the Hermit is known as the saint of beggars and the homeless. From its very beginning in the 12th century, St Giles in the Fields has been linked to vagrancy and homelessness. When leprosy became less common in England, the hospital started helping poor and needy people. So, seeing homeless people in the parish and churchyard has been common for a long time.

In 1585, Queen Elizabeth I ordered "destitute foreigners" to leave the City of London. Many of them came to St Giles in the Fields. Church records from the 17th century mention people fined for drinking on Sundays. This sad connection continued through the 18th century. Artists like William Hogarth and writers like Smollett showed this. Dispossesed Irish Catholics and poor Black Loyalists from America were especially noticeable.

In the 19th century, St Giles was still described as a place for "noisome and squalid outcasts." In 1731, St Giles and St George's churches worked together. They created a plan to help their many poor people. This was the St Giles workhouse. It was the first organized effort to help the poor and homeless in the parish. Over the next 200 years, it grew and improved. It became the basis for poor relief in the area.

Today, St Giles in the Fields church still helps homeless charities. But the main responsibility for helping the poor and homeless now belongs to the London Borough of Camden. However, you can still see homeless and struggling people in the St Giles area.

Other Features

The two paintings of Moses and Aaron next to the altar were done by Francisco Vieira the Younger. He was a court painter for the King of Portugal.

The mosaic Time, Death and Judgment by G. F. Watts used to be in St Jude's Church. It was made by Salviati.

The large stained-glass window at the east end of the church shows the transfiguration of Christ on mount Tabor.

Life at St Giles Church Today

Worship and Services

St Giles in The Fields is an active Christian church. It is part of the Church of England. It belongs to the Diocese of London. The church has a Rector, a Curate, and an assistant minister. Its worship follows the teachings of the Church of England. These are found in the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion and the Book of Common Prayer.

The church is open daily for quiet prayer. Morning Prayer is said every morning at 8:15 am. Holy Communion is held on Wednesdays at 1 pm. Sometimes, St Giles has a short service called Sung Compline on Wednesday evenings.

On Sundays, there are two services. Sung Eucharist is at 11 am, and Evensong is at 6:30 pm. The church often hosts guest preachers once a month at Evensong.

Services at St Giles use the Book of Common Prayer from 1662. They also use the King James Bible. St Giles is a member of the Prayer Book Society. Visitors are given prayer books and hymnbooks. You don't need to know the services to participate. More details are on the church website.

St Giles regularly holds Weddings, Funerals, and Christenings. These are for both church members and new people in the parish.

Professional singers provide music for Sunday morning services. On the first Sunday of the month, the Sung Eucharist is longer. It includes sung responses and the Creed. For Sunday Evensong, a volunteer choir sings. This choir started in 2005 and has up to 30 members. The choir has sung in many cathedrals.

The church year at St Giles follows the traditional Church of England Calendar. This includes Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter, and Trinity. Important festivals include Christmas Day, Epiphany, Candlemas, Ash Wednesday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Easter Day, Ascension Day, Whitsun, Trinity Sunday, and All Saints Day. There are also many smaller feast days. The Lord's Supper, or Holy Communion, is the main weekly service. It is held at 11:00 am on Sunday.

The patronal Feast of St Giles is celebrated on the Sunday closest to September 1. Rogation Sunday is marked by the Rector and church members. They perform the traditional beating of the bounds of the parish.

The Rector and church council offer a yearly Lenten Bible study. They also organize parish retreats and visits to other churches.

Community Mission

The St Giles & St George Charities work with the nearby parish of St George's Bloomsbury. They focus on helping people in need and supporting education. The charities give grants to local schools. They also provide almshouse housing in Covent Garden. Small grants are given to people facing hardship and homelessness. These charities continue the work of many old foundations in the St Giles area.

The Simon Community runs a weekly Street Cafe outside the church. This happens every Saturday and Sunday. Quaker Homeless Action has a lending library at St Giles. It provides books to homeless people every Saturday. Street Storage helps homeless people store their belongings safely. The church bells were cast in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Rectors of St Giles from 1547

| Date | Name | Other/previous posts |

|---|---|---|

| 1547 | Sir William Rowlandson | |

| 1571 | Geoffrey Evans | Presented to the living by Queen Elizabeth I |

| 1579 | William Steward | |

| 1590 | Nathaniel Baxter | Poet and Greek tutor to Sir Philip Sidney. Author of the Ourania. |

| 1591 | Thomas Salisbury | |

| 1592 | Joseph Clerk | |

| 1616 | Roger Maynwaring | Chaplain to King Charles I, Dean of Worcester, Bishop of St David's, Impeached by Parliament for treason and blasphemy for a sermon given at St Giles on 4 June 1628 in support of the Divine Right of Kings. |

| 1635 | Gilbert Dillingham | Schoolmaster of London |

| 1635 | Brian Walton | Bishop of Chester, compiler of the first Polyglot Bible |

| 1636 | William Heywood | Domestic Chaplain to Archbishop Laud, Chaplain to Charles I, Prebendary of St Paul's |

| English Commonwealth | Henry Cornish, Arthur Molyne and Thomas Case were "ministers" respectively of this church | Thomas Case, member of the Westminster Assembly of 1643. Refused the Engagement after the murder of Charles I and was confined to the Tower for six months for his part in a Presbyterian plot to recall Charles II. Chaplain to the King following the Restoration, he took part in the Savoy conference of 1661 but was ejected for nonconformity following the Act of Uniformity 1662. |

| 1660 | William Heywood | Returned on English Restoration |

| 1663 | Robert Boreman | Prebendary of Westminster admitted on 18 November 1663 to the rectory of St. Giles's-in-the-Fields, on the presentation of the King Charles II. |

| 1675 | John Sharp | Archdeacon of Berkshire, Prebendary of Norwich, Chaplain to Charles II, Dean of Canterbury, Archbishop of York, Lord High Almoner to Queen Anne, Commissioner for the Union with Scotland. |

| 1691 | John Scott | Canon of Windsor (a royal peculiar) |

| 1695 | William Hayley | Dean of Chichester, chaplain to Sir William Trumbull ambassador to Constantinople and Paris, chaplain to William III, buried in the chancel of the church. |

| 1715 | William Baker | Bishop of Bangor, Bishop of Norwich |

| 1732 | Henry Gally | Chaplain to George II |

| 1769 | John Smyth | Prebendary of Norwich |

| 1788 | John Buckner | Domestic Chaplain to the third Duke of Richmond and present at the taking of Havana. Later Bishop of Chichester |

| 1824 | Christopher Benson | Master of the Temple. Gave the first Hulsean lecture at Cambridge. Evangelical opponent of the Oxford Movement and coiner of term 'Tractarian'. |

| 1826 | James Endell Tyler | Canon Residentiary of St Paul's. Nearby Endell Street was named in his honour. |

| 1851 | Robert Bickersteth | Ordained Bishop of Ripon 18 June 1857. "He was regarded as one of the leaders of the evangelical school, and was strongly opposed to the introduction of any ceremonies or doctrines not strictly in accord with the opinions of his party" |

| 1857 | Anthony Thorold | Bishop of Rochester, Bishop of Winchester, As Bishop of Rochester he was instrumental in reviving the female Diaconate in the Anglican church through his ordination and encouragement of the Deaconess Isabella Gilmore. |

| 1867 | John Marjoribanks Nisbet | Canon Residentiary of Norwich |

| 1892 | Henry William Parry Richards | Prebendary of St Paul's |

| 1899 | William Covington | Prebendary and Canon of St Paul's |

| 1909 | Wilfred Harold Davies | |

| 1929 | Albert Henry Lloyd | |

| 1941 | Ernest Reginald Moore | |

| 1949 | Gordon Clifford Taylor | Served aboard HMS Arrow in the Atlantic Convoys and was chaplain aboard HMS Rodney during the bombardment of Cherbourg. Rural dean of Finsbury and Holborn. After the war He rebuilt and restored the bomb-damaged church and destroyed vestry house as well as saving the historic West Street Chapel from developers. Worked successfully with Austen Williams of St Martin-in-the-Fields to defeat the comprehensive redevelopment of Covent Garden. A defender of the traditions of the Church of England and the Book of Common Prayer. |

| 2000 | William Mungo Jacob | Archdeacon of Charing Cross |

| 2015 | Alan Cobban Carr | |

| 2021 | Thomas William Sander | Chaplain to the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment. |

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |