Commonwealth of England facts for kids

| 1649–1660 | |

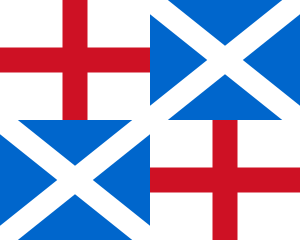

One of the various flags of the Commonwealth

|

|

| Preceded by | Second English Civil War |

|---|---|

| Including | |

| Followed by | Stuart Restoration (1660) |

| Leader(s) |

|

The Commonwealth was a period in English history when England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland were governed as a republic. This means they had no king or queen. This time lasted from 1649 to 1660. It began after the Second English Civil War and the execution of King Charles I.

The new republic was officially declared on May 19, 1649. At first, power was held by the Rump Parliament and a special group called the English Council of State. During this time, fighting continued in Ireland and Scotland. These conflicts were between the new government's forces and those who opposed them.

In 1653, the Parliament was dismissed. Oliver Cromwell became the Lord Protector, a powerful leader of England, Scotland, and Ireland. This new period was called the Protectorate. After Cromwell died, his son, Richard Cromwell, ruled briefly. But soon, the old Parliament was brought back. This led to the return of the monarchy in 1660.

Some people use "Commonwealth" to describe the whole period from 1649 to 1660. Others use it only for the years before Cromwell became Lord Protector in 1653.

Looking back, the republic didn't last long. For 11 years, England struggled to find a stable government. Many different ways of ruling were tried. But no lasting laws were passed. The only thing holding it together was Oliver Cromwell himself. He controlled the country through the powerful New Model Army.

After Cromwell died, his government fell apart. The monarchy he had overthrown was brought back in 1660. The new king quickly erased all changes made during the republic. Still, the idea of the Parliament's cause, called the "Good Old Cause", lived on. It later helped lead to England having a constitutional monarchy, where the king or queen shares power with Parliament.

The Commonwealth is also remembered for its military successes. Leaders like Thomas Fairfax, Oliver Cromwell, and the New Model Army won many battles. The English Navy, led by Robert Blake, defeated the Dutch in the First Anglo-Dutch War. This was an important step towards England becoming a powerful naval nation. In Ireland, however, this period is remembered for Cromwell's harsh control.

Contents

The Early Commonwealth (1649–1653)

The Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was formed after some members of the Long Parliament were removed. These removed members did not support putting King Charles I on trial. After the King's execution in January 1649, the Rump Parliament passed laws to create the new republic.

They got rid of the monarchy, the King's old advisory group (the Privy Council), and the House of Lords. This gave the Rump Parliament complete power. A new group, the English Council of State, took over many of the King's old jobs. This Council was chosen by the Rump Parliament, and most of its members were also Members of Parliament (MPs). However, the Rump Parliament needed the Army's support, and their relationship was often difficult.

Who Was in the Rump Parliament?

The Rump Parliament had fewer than 200 members. This was less than half the number of the original Long Parliament. Many members were gentry, which means they came from wealthy land-owning families. They were generally conservative. This meant they didn't want to change the existing laws or land ownership.

Challenges and Successes

For its first two years, the Rump Parliament faced money problems. There was also a risk of invasion from Scotland and Ireland. By 1653, Oliver Cromwell and the Army had largely dealt with these threats.

There were many disagreements among the Rump's members. Some wanted a true republic, while others still wanted some form of monarchy. Most of England's traditional rulers saw the Rump as an illegal government. But they also knew it was the only thing stopping the country from becoming a military dictatorship. High taxes, mostly to pay the Army, made the gentry unhappy.

Despite being unpopular, the Rump Parliament helped bring stability to England. It was a link to the old system and helped the country recover after a huge upheaval. By 1653, countries like France and Spain had recognized England's new government.

Changes Made by the Rump

The Rump Parliament kept the Church of England, but it removed bishops. It also allowed many independent churches to exist. However, everyone still had to pay taxes to the main church.

Some small improvements were made to laws and court procedures. For example, all court cases were now held in English, not in Latin. But there were no big changes to the main legal system. This would have upset the gentry, who liked the old laws because they protected their status and property.

The Rump also passed strict laws about people's behavior. They closed down theatres and made people strictly observe Sundays. Laws were also passed banning the celebration of Easter and Christmas. These rules made many people, especially the gentry, angry.

Why the Rump Parliament Ended

Oliver Cromwell and Thomas Harrison forced the Rump Parliament to close on April 20, 1653. The exact reasons are not fully clear. Some think Cromwell feared the Rump was trying to stay in power forever. Others believe the Rump was preparing for an election that might bring back people who opposed the Commonwealth. Many former members of the Rump believed their dismissal was illegal.

Barebone's Parliament (July–December 1653)

After the Rump Parliament was dismissed, Cromwell and the Army ruled alone for a short time. Cromwell didn't want a military dictatorship. So, he created a "nominated assembly." He thought the Army could easily control this group since Army officers chose its members.

This assembly was nicknamed Barebone's Parliament. Many wealthy people made fun of it, calling it an assembly of "inferior people." However, most of its 140 members were from the lesser gentry or higher social classes. One exception was Praise-God Barebone, a Baptist merchant, who gave the assembly its mocking name. Many members were well-educated.

The assembly had different groups with different ideas. Some were "Radicals" who wanted big changes, like getting rid of old laws. Others were "Moderates" who wanted small improvements. The "Conservatives" wanted to keep things as they were.

Cromwell hoped Barebone's Parliament would make reforms and create a new constitution. But the members disagreed on many important issues. Only 25 had been in Parliament before, and there were no qualified lawyers.

Cromwell seemed to expect this group of amateurs to make big changes without much guidance. When the Radicals gained enough support to stop a bill that would keep things the same in religion, the Conservatives and many Moderates gave their power back to Cromwell. He then sent soldiers to clear the rest of the assembly. Barebone's Parliament was over.

The Protectorate (1653–1659)

In 1653, Cromwell and the Army slowly changed how the Commonwealth was run. The English Council of State was dissolved by Cromwell. A new council, filled with his chosen men, took its place.

Three days after Barebone's Parliament ended, a new set of rules called the Instrument of Government was adopted. This created a new government structure known as The Protectorate. This new constitution gave Cromwell huge powers as Lord Protector. Many people noticed that his role and powers were very similar to those of a king.

On April 12, 1654, Scotland was officially joined with England. This was called the Tender of Union. It declared that "the people of Scotland should be united with the people of England into one Commonwealth." A new coat of arms, including the Scottish Saltire, was created to show this union.

First Protectorate Parliament

Cromwell and his Council of State spent months preparing for the First Protectorate Parliament. They wrote 84 bills for it to consider. This Parliament was freely elected, as much as elections could be in the 1600s. Because of this, it had many different political groups. It didn't achieve any of Cromwell's goals and passed none of his bills. Cromwell dissolved it as soon as the law allowed.

Rule of the Major-Generals and Second Protectorate Parliament

Cromwell decided that Parliament wasn't working well. So, he set up a system of direct military rule in England. This period is known as the Rule of the Major-Generals. England was divided into ten regions. Each region was governed by one of Cromwell's Major-Generals. These generals had great power to collect taxes and keep the peace.

The Major-Generals were very unpopular. Many of them even urged Cromwell to call another Parliament. They hoped this would make his rule seem more legitimate.

Unlike the previous Parliament, this new election specifically stopped Catholics and Royalists from running or voting. Because of this, the Parliament was filled with members who agreed more with Cromwell's ideas. The first big bill they discussed was the Militia Bill, but it was voted down. This meant the Major-Generals could no longer collect taxes to support their rule, and their power ended.

The second important law passed was the Humble Petition and Advice. This was a big change to the constitution. It gave Parliament certain rights, like meeting for a fixed three-year term. It also said only Parliament could collect taxes. As a compromise, it suggested making the Lord Protector a hereditary position, like a king. Cromwell refused the title of King, but he accepted the rest of the law. It was passed on May 25, 1657.

A second session of this Parliament met in 1658. It allowed MPs who had been excluded before (due to Catholic or Royalist leanings) to take their seats. However, this made the Parliament less willing to follow Cromwell's wishes. It didn't achieve much and was dissolved after a few months.

Richard Cromwell and the Third Protectorate Parliament

When Oliver Cromwell died in 1658, his son, Richard Cromwell, became Lord Protector. Richard had never served in the Army. This meant he couldn't control the Major-Generals, who had been the source of his father's power.

The Third Protectorate Parliament met in January 1659. Its first act was to confirm Richard as Lord Protector. But it quickly became clear that Richard had no control over the Army. Divisions grew in Parliament. One group wanted to bring back the Rump Parliament. Another preferred the current system. As the arguments grew, Richard dissolved Parliament. He was soon removed from power. The remaining Army leaders then brought back the Rump Parliament. This set the stage for the return of the Monarchy a year later.

The End of the Commonwealth (1659–1660)

After the Army leaders removed Richard Cromwell, they brought back the Rump Parliament in May 1659. Charles Fleetwood became a top army commander. However, Parliament tried to ignore the Army's power. On October 12, 1659, Parliament removed General John Lambert and other officers. The next day, Lambert ordered Parliament's doors shut, keeping members out.

Into this confusing situation, General George Monck marched his army south from Scotland. Lambert's army began to abandon him, and he returned to London almost alone. On February 21, 1660, Monck brought back the old members of the Long Parliament. They prepared laws for a new Parliament.

Fleetwood lost his command. Lambert was sent to the Tower of London but escaped a month later. Lambert tried to restart the civil war, calling on supporters of the "Good Old Cause" to rally. But he was recaptured by Colonel Richard Ingoldsby. The Long Parliament dissolved itself on March 16.

On April 4, 1660, Charles II issued the Declaration of Breda. This document explained the conditions for him to accept the crown of England. Monck organized a new Parliament called the Convention Parliament. It met on April 25. On May 8, it declared that King Charles II had been the rightful monarch since his father's execution in 1649.

Charles returned from exile on May 23. He entered London on May 29, his birthday. To celebrate, May 29 became a public holiday, known as Oak Apple Day. He was crowned king on April 23, 1661.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Mancomunidad de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Mancomunidad de Inglaterra para niños