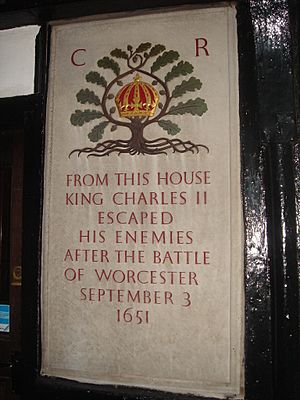

Escape of Charles II facts for kids

After the big Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651, King Charles II (who was already King of Scotland) had to run away from England. His army, the Royalists, had been completely beaten by Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army. Charles had help from many loyal families. He first tried to escape to Wales, then to Bristol dressed as a servant, and then to the south coast at Charmouth. Finally, he rode east to Shoreham and sailed to France on October 15, 1651.

During his six-week escape, he traveled through many English counties. The most famous part of his journey was when he had to hide in an oak tree. This happened while Parliament's soldiers were searching the area. There was a huge reward of £1000 offered for anyone who could help capture Charles.

Contents

Charles's Great Escape Begins

Running from Worcester

After losing the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651, King Charles quickly left his home in Worcester. He slipped out a back door just as the Parliamentary soldiers arrived. He fled the city through St Martin's Gate, heading north. With him were Lord Wilmot, Lord Derby, Charles Giffard, and other loyal friends.

Charles wanted to go to London, not Scotland, which most of his group preferred. He only told Lord Wilmot his secret plan. They agreed to meet later. It was getting dark, and Charles needed his small group of officers to help him.

The royal group, about sixty mounted officers, first rode north from Worcester. Their exact path is not fully known. They may have passed through Kidderminster. Lord Derby suggested Boscobel House in Shropshire as a safe place. He had hidden there before with the Pendrell brothers, who were Catholic tenants. Charles Giffard, who owned Boscobel, agreed. But he thought another house on his land, White Ladies Priory, would be even safer.

So, the group changed direction towards Stourbridge. Even though Parliament's soldiers were in the town, Charles managed to pass through without being noticed. They continued north, stopping briefly at Wordsley. They reached White Ladies in the early morning of September 4.

Hiding at Boscobel and a Try for Wales

At White Ladies, the King met George Pendrell. George called his brother Richard, who farmed nearby. Together, they disguised the King as a farm worker. He wore old, rough clothes: a leather jacket, green pants, and a coarse linen shirt. Richard even cut the King's hair short on top, but left it long on the sides. It was decided that Charles would be safer with almost no one else. So, all his followers, except Lord Wilmot, left.

At dawn, in heavy rain, Charles moved from White Ladies to a nearby wooded area called Spring Coppice. He hid there with Richard Pendrell. Soon after, local soldiers stopped at White Ladies. They asked if the King had been seen. The soldiers were told he had left earlier. They believed this and rode past, but Charles saw them. He later remembered: "I stayed in this wood all day without food or drink. Luckily, it rained the whole time, which I believe stopped them from searching the wood for people who might have fled there."

The Pendrells taught Charles how to speak with a local accent. They also showed him how to walk like a farm worker. They said they didn't know how to get him safely to London. But they knew of a man named Francis Wolfe who lived near the River Severn. Wolfe's house, Madeley Court, had many hiding places. After dark, Richard Pendrell took Charles to Hobball Grange for a meal. Then they immediately left for Madeley. They hoped to cross the River Severn into Wales, where the Royalists had strong support.

At Evelith Mill, a local miller challenged them. Charles and Richard ran away. They later found out the miller was also a Royalist hiding other defeated soldiers. Charles and Richard reached Madeley Court near midnight on September 5.

At Madeley, Wolfe told them his house was no longer safe. But he let Charles hide in a barn. Richard and Wolfe then went to check the Severn crossings. They found the river was heavily guarded. Charles and Richard had to go back to Boscobel. They waded through a stream and stopped at White Ladies. There, they learned Lord Wilmot was safe at nearby Moseley Hall. Charles's feet were very sore and bleeding because his shoes were too small and rough. They reached Boscobel House around 3 AM on September 6, and Charles's feet were cared for.

Hiding in the Royal Oak Tree

Colonel William Careless, who had fought at Worcester, also arrived at Boscobel House. Careless suggested that he and the King spend September 6 hiding in a large oak tree nearby. This tree later became known as the Royal Oak. While they were in the tree, Parliament's soldiers searched the woods around them. The King was very tired and slept for some time. Careless supported him, and when his arms got tired, he had to gently pinch the King to wake him up and keep him safe. They returned to Boscobel House that evening.

Meanwhile, another Pendrell brother, Humphrey, reported something important. He had been questioned by a Parliament colonel at the local militia office. The colonel asked if the King had been at White Ladies. Humphrey convinced the officer he had not been there. The colonel reminded Humphrey about the £1000 reward for catching the King. He also mentioned the "penalty for hiding the King, which was death without mercy." This made it even more urgent to get Charles out of the country quickly. Charles spent that night hiding in one of Boscobel's secret priest holes.

Safe at Moseley Hall

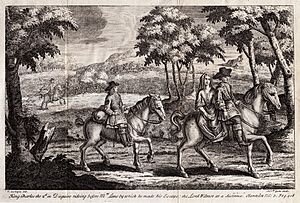

Lord Wilmot suggested that Charles leave Boscobel for Moseley Hall. Late on the evening of September 7, Charles rode an old horse provided by Humphrey Pendrell, the miller. All five Pendrell brothers and Francis Yates went with the King. Soon after leaving Boscobel, the horse stumbled. Humphrey Pendrell joked that it was "no wonder, for it had the weight of three Kingdoms upon its back." The group stopped at Pendeford Mill, where Charles got off the horse because it was not safe to keep riding. Three of the brothers took the horse back. Richard and John Pendrell, along with Francis Yates, continued with the King to Moseley Hall.

At Moseley, the home of Thomas Whitgrave, Charles was given a meal and dry clothes. Whitgrave's Catholic priest, John Huddleston, washed the King's bruised and bleeding feet. Charles was very grateful. He told Huddleston, "If God helps me become King, you and all your people will have as much freedom as any of my subjects." Charles hid at Moseley Hall for that night and the next two days. He slept in a bed for the first time since September 3. The next morning, he saw some of his defeated Scottish soldiers passing by.

When Parliament's soldiers arrived at the Hall, Charles was quickly hidden in a secret priest hole behind a bedroom wall. The soldiers accused Whitgrave of fighting for the King at Worcester. Whitgrave convinced them he was too weak to help any Royalist fugitives. The soldiers left without searching the house.

Trying to Escape Through Bristol

The King no longer felt safe at Moseley Hall. Wilmot suggested he move to Bentley Hall near Walsall. This was the home of Colonel John Lane and his sister Jane Lane. Wilmot had learned that Jane had a special pass. It allowed her and a servant to travel to Abbots Leigh in Somerset to visit a friend. Abbots Leigh was near the important port city of Bristol. Wilmot thought the King could use this pass. He would travel to Bristol disguised as Jane's servant and then take a ship to France. Shortly after midnight on September 10, the King left for Bentley Hall, arriving early in the morning.

Charles dressed as a farmer's son and used the fake name 'William Jackson'. The group set out, with Charles riding the same horse as Jane Lane. They were joined by Jane's sister, Withy Petre, her husband John Petre, and Henry Lascelles, another Royalist officer. Wilmot refused to wear a disguise. He rode half a mile ahead, saying he would pretend to be hunting if anyone stopped him. The group rode through Rowley Regis and Quinton to Bromsgrove.

At Bromsgrove, the horse Charles and Jane were riding lost a shoe. The King, acting as a servant, took the horse to a blacksmith. Charles later told the story: "As I was holding my horse's foot, I asked the smith what news. He told me there was no news, except the good news of beating the Scottish 'rogues'. I asked if any English people who joined the Scots were caught. He said he hadn't heard if that 'rogue', Charles Stuart, was caught. But some others, he said, were taken. I told him that if that 'rogue' were caught, he deserved to be hanged more than all the rest, for bringing in the Scots. The blacksmith said I spoke like an honest man, and we parted."

The group reached Wootton Wawen, where New Model Army cavalry were gathered outside an inn. John and Withy Petre went ahead. The King, Jane Lane, and Henry Lascelles bravely rode through the soldiers. They continued through Stratford-upon-Avon to Long Marston. They spent the night of September 10 at the house of John Tomes, another relative of Jane's. Here, to keep up his servant disguise, the cook made him work in the kitchen. Charles was clumsy at winding up the jack used to roast meat. The cook asked him, "What countryman are you that you don't know how to wind up a jack?" Charles excused himself by saying that as the son of poor people, he rarely ate meat, so he didn't know how to use one. His story was believed, and he was not recognized.

On September 11, they continued through Chipping Campden to Cirencester, where they spent the night. The next morning, they traveled to Chipping Sodbury and then to Bristol. They arrived at Leigh Court, the home of George and Ellen Norton in Abbots Leigh, late on the afternoon of September 12. The Nortons did not know the King's true identity during his three-day stay. However, their butler, Pope, who had been a Royalist soldier, immediately recognized him. Charles confirmed his identity to Pope, who later let Wilmot into the house secretly. Pope also tried to find a ship for the King at Bristol port. But he found no ships would be sailing to France for another month. While at Abbots Leigh, Charles avoided suspicion. He asked a servant, who had been in the King's personal guard at Worcester, to describe the King's appearance. The man looked at Charles and said, "The King was at least three fingers taller than [you]."

Since no ships were found, Pope suggested the King hide at the home of Colonel Francis Wyndham. He was another Royalist officer who lived forty miles away in the village of Trent. This was near Sherborne on the border of Somerset and Dorset. The Wyndham family was known to both Wilmot and Charles. Charles and Wilmot decided to head for the south coast with Jane. However, Mrs. Norton suddenly went into labor and had a baby that did not survive. Jane could not leave Abbots Leigh without causing suspicion. So, Pope wrote a fake letter to Jane. It said her father was very ill and she was needed at home.

On the morning of September 16, Charles set out for Castle Cary, where he spent the night. The next day, he arrived at Trent.

From Trent to Charmouth and Back

The King spent the next few days at Trent House. Wyndham and Wilmot tried to find a ship from Lyme Regis or Weymouth. Wyndham contacted Captain Ellesdon, a friend in Lyme Regis. One of Ellesdon's tenants, Stephen Limbry, was sailing from Charmouth to Saint-Malo the following week. It was decided that Charles and Wilmot would board the ship. They would pretend to be merchants traveling to collect money from someone who owed them.

At Charmouth, Charles waited at the Queen's Arms Inn. Wilmot was negotiating with Captain Limbry to take them to France. To explain why they needed to leave quietly at night, the landlady was told a secret. Their guests were a couple running away to get married (Wyndham's cousin and Wilmot pretending to be the bride and groom). Charles was their manservant. However, Limbry did not show up. He later said his wife had locked him in his bedroom because she was worried for his safety.

Stranded on the beach at dawn, with no boat, Charles and Wyndham decided to go to nearby Bridport. They hoped to find out what happened to Limbry there. When they arrived, they found the town full of Parliament's soldiers. These soldiers were about to sail for Jersey. Charles bravely walked through the soldiers to the best inn and arranged for rooms. The stable worker looked at the King and said, "Sir, I know your face." But Charles convinced him that they had both been servants at the same time for a Mr. Potter of Exeter.

Meanwhile, Wilmot had stayed behind in Charmouth because his horse lost a shoe. The inn's stable worker, a Parliament soldier, became suspicious. His suspicions were confirmed when a blacksmith told him that one of the horse's shoes had been made in Worcestershire. Learning that the "eloping couple" had gone to Bridport, the stable worker told his commanding officer. The officer rode after them. Wilmot, also trying to find the King in Bridport, had gone to the wrong inn. He sent a servant to find Charles and sent a message that they should meet outside the town. When they met, they agreed they should return to Trent. There were too many soldiers in the area. They took a small country road (Lee Lane) heading north. They just missed a group of soldiers riding from Charmouth. A modern stone memorial in Lee Lane remembers this narrow escape.

Losing their way, Charles and Wilmot decided to stop overnight in the village of Broadwindsor, at The George Inn. That evening, the local police officer arrived with forty soldiers. They were to stay at the inn on their way to Jersey. Luckily for Charles, attention was drawn away. One of the women traveling with the soldiers went into labor. This allowed the King to escape the next morning and return to Trent House.

From Trent to Shoreham and Escape to France

Charles spent the next twelve nights at Trent House. They continued to look for a way to France. The night he returned to the house, he met a cousin of Edward Hyde. This cousin knew Colonel Edward Phelips. Wyndham himself suggested asking his friend John Coventry for help. Wilmot contacted both Phelips and Coventry, and they promised to help Charles. A ship was booked from Southampton for September 29. But that became impossible when the ship was taken by the army to transport troops to Jersey. Phelips, Coventry, and Doctor Henchman decided to try the Sussex coast. They contacted Colonel George Gunter.

On October 6, the King, Julia Coningsby, and Henry Peters left Trent for Heale House. This house was at Woodford, between Salisbury and Amesbury. It was the home of Katherine Hyde. As soon as Charles arrived, he pretended to leave permanently. He rode around the area, visited Stonehenge, and then secretly returned. Only Mrs. Hyde knew he was back. On October 7, Wilmot visited Colonel Gunter. Gunter found a French merchant, Francis Mancell, who lived in Chichester. Together, they arranged with Captain Nicholas Tattersell to take the King and Wilmot from Shoreham. They would sail in a coal boat called Surprise for £80.

In the early hours of October 13, the King and Phelips rode from Heale House to Warnford Down. There, they met Wilmot and Gunter. From there, the group set out for Hambledon. Gunter's sister lived there, and they stayed at her house for the night. The next day, they rode fifty miles to the fishing village of Brighthelmstone (now Brighton). They stopped at Houghton for a meal. Then they rode to the village of Bramber, which was full of soldiers. Gunter decided they would bravely ride through the village. As they were leaving, about fifty soldiers rode quickly towards them. They dashed past and up a narrow lane, giving the travelers a big scare. At the village of Beeding, Gunter left the group to ride alone. The rest of the group continued by a different route. They met Gunter at the George Inn at Brighthelmstone on the evening of October 14.

Gunter knew the George Inn was a safe place to stay the night. However, when Captain Tattersell arrived, he recognized the King and was very angry. His anger drew the attention of the inn-keeper, who also recognized Charles. The inn-keeper had once been a servant to Charles's father, King Charles I. Charles, in turn, recognized the inn-keeper. He told Gunter, "The fellow knows me and I him; I hope he is an honest fellow." Meanwhile, the angry Tattersell demanded an extra £200 as payment for the danger. Once the King and Gunter agreed, Tattersell fully promised to help the King. The King rested briefly before setting out for the boat at Shoreham, a few miles west.

Around 2 AM on October 15, the King and Wilmot boarded the Surprise. The boat sailed on the high tide five hours later. Two hours after that, a group of cavalry arrived in Shoreham to arrest the King. They had orders to search for "a tall, black [haired] man, six feet two inches in height."

The King and Wilmot landed in France at Fécamp, near Le Havre, on the morning of October 16, 1651.

Life in France and Return to England

The next day, Charles went to Rouen and then to Paris to stay with his mother, Queen Henrietta Maria. He would not return to England for nine years.

Oliver Cromwell died in 1658. After his death, there were two years of political confusion. This led to the return of the monarchy in 1660. When Charles returned to England in 1660, he gave money and gifts to some of the people who had helped him. This included the Pendrell brothers and Jane Lane. Thomas Whitgrave and Richard Pendrell received yearly payments of £200. Richard Pendrell's family would receive £100 every year forever. The other Pendrell brothers received smaller payments. Payments to the Penderels (another spelling) are still made to some family members today. The payments to Whitgrave and Jane Lane eventually stopped.

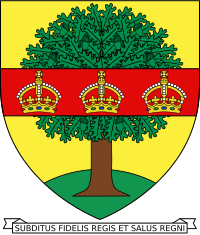

Some families who helped the King were given special coats of arms, or additions to their existing ones. Colonel Careless's coat of arms showed an oak tree on a gold background with a red stripe. On the stripe were three royal crowns. These crowns stood for the three Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland. The Penderels used similar arms, but with different colors. The Lanes' coat of arms had an added section with the three lions of England.

Remembering the Escape

- Soon after Charles became King again, Isaac Fuller was asked to paint five pictures about the escape. These paintings show the King at White Ladies, in Boscobel Wood, in the oak tree with Colonel Careless, riding Humphrey Penderel's horse, and riding to Bristol with Jane Lane. These paintings are now in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

- In 1664, May 29, the King's birthday, was named Oak Apple Day by law. A special church service was added to the prayer book. For over 200 years, people celebrated the King's birthday by wearing a sprig of oak leaves. This was to remember the events. This tradition is not widely followed anymore.

- Hundreds of inns and pubs across the country are called 'The Royal Oak'. Eight ships of the Royal Navy were also named Royal Oak.

- The escape from England is remembered each year around Oak Apple Day with a yacht race. It goes from Brighton to Fecamp and is called The Royal Escape Race.

- Another event happens every year at the Royal Hospital Chelsea on Founder's Day. This is close to Oak Apple Day. On Founder's Day, members of the British Royal Family review the old soldiers living at the Royal Hospital.

- The Monarch's Way is a long walking path, 625 miles long. It roughly follows the escape route, starting at the battlefield in Worcester and ending at Shoreham.

- The escape is the main story in William Harrison Ainsworth's 1871 book Boscobel, or, The Royal Oak.

- Georgette Heyer's 1938 book, Royal Escape, is also based on this story.

- Gillian Bagwell's 2011 book The September Queen tells the story of Jane Lane's part in Charles's escape.

Images for kids

-

"The Royal Escape Close-Hauled in a Breeze" by Willem van de Velde the Younger

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |