Bombardment of Cherbourg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bombardment of Cherbourg |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II, Operation Neptune–Operation Overlord | |||||||

A heavy German coast artillery shell falls between USS Texas (background) and USS Arkansas while they duel with Battery Hamburg |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3 battleships 2 heavy cruisers 2 light cruisers 11 destroyers 3 minesweeper squadrons |

20 casemated batteries Battery Hamburg German "Fortress" status elements of 4 divisions |

||||||

The Bombardment of Cherbourg happened on June 25, 1944, during World War II. Ships from the United States Navy and the British Royal Navy attacked German defenses near the city. They fired their big guns to help U.S. Army soldiers fighting in the Battle of Cherbourg.

During this attack, the Allied naval forces fought against German coastal batteries. They also gave close support to the soldiers on the ground. The bombardment was supposed to last two hours but was extended to three. This extra time helped the army units push into Cherbourg's streets. German resistance in the city continued until June 29, when the Allies finally captured the port. After that, it took several weeks to clear the port so it could be used.

When the Allies landed in Normandy, the Germans wanted to trap them there. They also wanted to stop the Allies from using the important port at Cherbourg. This would cut off Allied supplies. By mid-June, U.S. soldiers had surrounded the Cotentin Peninsula. However, their advance had slowed down. The Germans then started destroying the port's facilities.

To counter this, the Allies increased their efforts to capture Cherbourg. By June 20, three groups of soldiers, led by General "Lightning Joe" Collins, were very close to the German defenses. Two days later, the main attack began. On June 25, a large group of navy ships started a heavy bombardment of the city. Their goal was to silence the German coastal guns and help the attacking soldiers.

The naval force was split into two groups. Each group had different warships, like battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and minesweepers. Each ship was given specific targets on land. German shells could hit targets up to 15,000 yards away. Some German shells even landed very close to the moving Allied ships. Several Allied ships were hit, but many German shells did not explode. When hit, the large Allied ships could often pull back. Allied destroyers would then create smoke screens to hide them.

After the battle, Allied reports showed that the smaller ships were the most helpful. They could hit specific targets up to 2,000 yards inland. This was very important for supporting the soldiers on the ground. The heavy guns from the bigger ships hit 22 of their 24 assigned targets. However, they could not completely destroy any of them. This meant soldiers still had to attack these positions to make sure the guns could not be used again. When the city fell, the German guns were still pointing out to sea. They could have been turned to fire at the advancing Allied troops.

Contents

Why Cherbourg Was Important

When German commanders realized the Normandy landings were the main attack, they tried to limit the Allied forces. They also prepared for a counter-attack. German fast attack boats from Cherbourg were moved to Saint-Malo. Four German destroyers from Brest tried to reach Cherbourg but were sunk or damaged.

By June 14, the Germans were trying to stop the Allies from using Cherbourg's big port. They blocked, mined, and destroyed its harbor. A strong storm in the English Channel then damaged the Allied artificial port, Mulberry A. This storm lasted until June 22. Moving supplies ashore became very difficult. The Allies urgently needed Cherbourg's port.

By June 18, Allied soldiers had sealed off the Cotentin Peninsula. But the German defense line became strong, and the American advance stopped. Cherbourg had a German force of 40,000 soldiers. Their new commander, as of June 23, was Generalleutnant Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben. Adolf Hitler believed the Allied invasion would fail without Cherbourg. He ordered it to be made "impregnable," meaning impossible to capture. He gave it "fortress" status. The American ground forces lost over 2,800 dead and 13,500 wounded to capture it.

The Germans had placed many coastal guns around Cherbourg. There were twenty casemated batteries, which are protected gun positions. Fifteen of these guns were 150 mm (about 6 inches) or larger. Three were 280 mm (about 11 inches). Many smaller 75 mm and 88 mm guns were also present. Some of these could be turned inland to fire at advancing soldiers.

To support the ground attack, Rear Admiral Morton Deyo started planning a naval bombardment on June 15. While planning, a late June storm hit the English Channel. It scattered Deyo's ships. They had to gather again in Portland Harbour, Dorset. On the Cotentin Peninsula, the U.S. Army VII Corps had made some progress but was then stopped by strong German resistance. The naval bombardment plan became complicated. The 9th, 79th, and 4th Divisions were now very close to the city.

An army officer was on board USS Tuscaloosa. He helped communicate between the different military branches. The original plan for a three-hour navy-only bombardment was shortened to ninety minutes. The targets were limited to those chosen by the army.

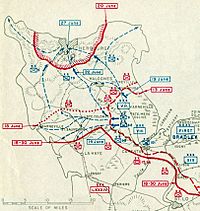

To help the Allied advance, a special naval force (CTF 129) was formed on June 25, 1944. Rear Admiral Morton Deyo led this force. Its job was to silence coastal batteries that might fire on advancing soldiers. It also provided fire support when soldiers asked for it. The navy also worked with army air force bombers. They tried to stop German ammunition from reaching the front lines. As soldiers got closer, the navy followed directions from spotter planes.

Battle Groups

The naval force was split into two groups: Battle Group 1 and Battle Group 2.

- Battle Group 1, led by Admiral Deyo, was to bombard Cherbourg. This included the inner harbor forts and the area to the west. This group had the battleship USS Nevada, cruisers USS Tuscaloosa, USS Quincy, HMS Glasgow, and HMS Enterprise. It also had six destroyers.

- Battle Group 2, led by Rear Admiral Carleton Fanton Bryant, was assigned to "Target 2," which was Battery Hamburg. This strong German battery was located near Fermanville, about 6 miles east of Cherbourg. Nevada from Group 1 was supposed to use its main guns to silence this powerful German position. Battle Group 2 would then finish destroying it. This group included the battleships USS Texas and USS Arkansas, and five destroyers.

Before the main ships arrived, US Minesweeping Squadron 7 and the British 9th Minesweeping Flotilla cleared paths through the water. They removed mines along the east and north coasts of Cherbourg. These minesweepers often came under fire from German shore batteries. As the bombardment continued, the minesweepers cleared more channels closer to the harbor.

Above, General "Pete" Quesada's IX Army Air Force provided fighter planes to protect the ships. Other planes helped by looking for German submarines and flying combat air patrols. British Grumman TBF Avenger planes also helped. Six British destroyers formed an anti-submarine screen, and the British 159th Minesweeping Flotilla also assisted.

Controlling the Fire

Because of concerns from ground commanders, all long-range shots on sea-facing batteries were canceled. Only "call fires" were allowed. This meant ships would only fire when asked by soldiers on the ground. Three batteries were chosen as specific navy targets. Any batteries that fired on the ships also became targets.

Ships had spotter planes flying over Cherbourg. From 9:40 AM until noon, ships were only allowed to fire if they were attacked. Soldiers on the ground also helped direct fire. P-38 Lightning planes from the IX Army Air Force flew from England. They provided air patrols, attacked targets, and gave close support to the soldiers. General Collins, leading VII Corps, made sure that naval fire control teams joined the infantry units as they neared German defenses.

Each firing ship had an army artillery officer on board. This officer knew where Allied troops were. He helped decide if it was safe to fire at a target. The army officer decided if firing would endanger Allied personnel. The ship itself controlled the actual firing. The ground teams watched where the shells landed and told the ships how to adjust their aim.

Air spotters worked in pairs, one spotting and one escorting. They could talk to each other and to the ships. Every ship had radios to talk to all types of aircraft. Another way to control fire was through a mix of air-to-ground-to-sea communication. Army observation planes spotted targets for a ground control team. This team then relayed the information to the ships.

The Bombardment Begins

At 9:40 AM, Battle Group 1 reached a point about 15 miles north of Cherbourg. Minesweepers cleared paths for both battle groups. The ships arrived in their firing areas without being shot at. Around noon, as the ships moved slowly towards the shore, German shells started falling. These shells came from a village called Querqueville, about 3 miles west of Cherbourg.

Four British gunboats started making a smoke screen to protect the minesweepers. HMS Glasgow and HMS Enterprise, with their spotter planes, began firing back at the German batteries. In just 30 minutes, every minesweeper had shells landing very close to them, but none were hit. Admiral Deyo called them back, and they stayed out of range for the rest of the battle.

At 9:55 AM, Battle Group 2 entered its firing area. Spotter planes for Texas and Arkansas were ready. The plan was for Nevada to start firing on Battery Hamburg. But Admiral Deyo sent a message canceling Nevada's long-range bombardment. He told them to wait until noon or fire only in self-defense. Group 2 was to join Group 1 by noon.

American troops had already captured two smaller targets. Spotters said these areas were "surrounded by dead Germans." Strong currents off Normandy slowed the battleships. Arkansas made radio contact with its ground control team. It moved closer, to 18,000 yards, and began firing on Battery Hamburg. Arkansas's old fire control system made it hard to aim. Her shots did no damage.

As Group 2 moved into the battery's firing range, the German guns opened fire. The minesweepers were all hit with near misses. The destroyer Barton was hit by a shell that didn't explode. It landed in her back engine room. She fired back at the German battery without air or ground spotting. All minesweepers were splashed by near misses. The destroyer Laffey was hit by another dud shell in her front left side. The crew removed it and threw it overboard.

Group 2 then started firing at Battery Hamburg, which was hidden by smoke. Texas had three shells land very close to her front. She turned sharply to avoid them. She was then hit with near misses every 20 to 30 seconds from a new battery. The large Battery Hamburg was focusing on the minesweepers and destroyers. The destroyer O'Brien was hit near her bridge, which knocked out her radar. She had to sail away blindly through a smoke screen. The minesweepers and the three damaged destroyers were called back. The destroyers fired their 5-inch guns as they left.

At 12:20 PM, Group 1 destroyers made smoke to protect the larger ships. They moved closer to shore to fire more effectively at the Querqueville battery. German fire focused on HMS Glasgow and Enterprise. Glasgow was hit twice but could keep fighting. After two hours, all four German guns were temporarily silenced.

Air spotters followed the action. Pairs of Spitfire planes were supposed to stay over their targets for 45 minutes. Only half of them made it. The others were driven off by anti-aircraft fire, had engine trouble, or couldn't find their targets. Soon after, Texas was hit by a German 280 mm (11-inch) shell. It hit the top of the ship's armored control tower. The shell did not go through the armor but exploded. It ripped up the deck of the bridge. The ship's helmsman, a 21-year-old sailor, was killed. He was the first and last combat death on board the Texas. The captain was outside the bridge and was not hurt. The order was given to leave the bridge, and the crew moved to the armored control tower to continue the battle.

At 12:12 PM, the first request for fire came from VII Corps ground teams. Following their directions, Nevada and Quincy destroyed the fortified target in 25 minutes. They continued to hit other targets for about three hours. Tuscaloosa was firing at different strong points as directed by ground control. Anti-aircraft fire hit her two Spitfire spotter planes, forcing them to leave. In the first hour, Ellyson found a coastal battery near Gruchy. Glasgow and her air spotters silenced it with 54 rounds. The destroyer Emmons fired at Fort De l'Est, a fort on one of the harbor walls. By the time the fort was silenced, a hidden battery started firing close to the ship from 15,000 yards away. Rodman dropped smoke, and Emmons pulled back.

Extending the Attack

At 1:20 PM, ten minutes before the bombardment was supposed to end, Admiral Deyo realized the mission wasn't finished. He signaled VII Corps, asking, "Do you wish more gunfire? Several enemy batteries still active." The Querqueville battery had started firing again. It hit near Murphy four times in 20 minutes. Tuscaloosa helped, scoring a direct hit that caused flames. With splinters and splashes covering her deck, Murphy dodged behind a smoke screen. Ellyson and Gherardi joined in. Quincy fired for half an hour, then Nevada silenced the battery again. Later, as the ships left, the battery opened fire once more. The ships had endured a long day of near misses. The battery near Gruchy also started firing again. HMS Glasgow and Rodman fired back. The batteries around Cherbourg seemed able to fire accurately at any ship within 15,000 yards. Rodman pulled out of range.

Navy personnel were assigned to army units as spotters. They directed all fire more than 2,000 yards inland. This allowed the ships to safely hit targets far inland, turning German tanks into "scrap metal." Protected bunkers were "powdered," and gun positions were "tossed skyhigh." German shore batteries, in turn, fired accurately, causing splashes and near misses around Deyo's ships.

In Group 2, moving west to join Group 1, Texas was turning sharply to avoid near misses. Then, one of the German 280 mm shells hit the hull and landed next to a sailor's bed, but it was also a dud. At 1:35 PM, one of the large guns in Battery Hamburg was knocked out by Texas. Texas and Arkansas continued firing at Battery Hamburg and another nearby battery through the afternoon. When they moved back into the firing range, Battery Hamburg's three remaining guns targeted Texas. A nearby 105 mm battery targeted Arkansas. Both ships maneuvered, and the two remaining destroyers made smoke. All escaped without damage.

At 2:02 PM, VII Corps replied to Deyo, "Thanks very much—we should be grateful if you would continue until 15:00." VII Corps was about to break into Cherbourg's city streets. Fort des Flamand, at the eastern end of the harbor, had eight 88 mm guns. These guns were holding up a regiment of the 4th Division. Ground control asked for naval support. Hambleton began firing, but large shells from Battery Hamburg started falling around her from 14,250 yards away. She pulled back. Then Quincy was able to silence the fort. Nevada turned from Battery Hamburg and attacked targets on the west side of Cherbourg. These targets might have fired inland at the advancing soldiers. For over 20 minutes, Nevada was repeatedly hit with near misses. Two shells even went through her upper structure, and another missed by only 25 feet.

An hour later, following General Collins' new deadline of 3:00 PM, Admiral Deyo ordered a cease-fire. The ships began leaving the bombardment area. Group 2 headed back to Portland, England, at 3:01 PM. The flagship Tuscaloosa received another call for fire. The targets were 75 mm field guns in protected positions on the dock at the entrance to Cherbourg's naval base. Tuscaloosa kept firing as she moved out to sea. She fired accurately from 25,000 yards and even from another mile and a half further away.

Results of the Bombardment

On June 29, when the last German resistance in Cherbourg was defeated, General Collins wrote to Admiral Deyo. He said that the "naval bombardment of the coastal batteries and the strong points around Cherbourg... results were excellent." He added that it "did much to engage the enemy's fire while our troops stormed into Cherbourg from the rear." After inspecting the port defenses, an army officer reported that the targeted guns could not be used again. Those that could have been turned inland were still pointing out to sea when the city fell.

Reports from German prisoners spoke of the fear they felt from the bombardment. However, there is no proof that naval gunfire caused huge destruction to the German guns themselves. Because the guns were not destroyed, soldiers had to capture them. Still, the naval gunfire was good at neutralizing the German batteries. It disabled 22 of their 24 assigned targets. During the bombardment, German gun positions were silent for long periods. This was later thought to be because the German gunners lost their morale, not because the guns were destroyed. The fire support from the task force's smaller ships was more effective. Allied reports after the bombardment said this was the most helpful part of the attack.

The amount of fire was significant. The Allied Supreme Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, later wrote that the "final assault was greatly helped by heavy and accurate naval gunfire." German General Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel was told by von Schlieben that further resistance was useless. This was partly due to "heavy fire from the sea." Admiral Theodor Krancke wrote in his war diary that one reason Cherbourg fell was a "naval bombardment of a hitherto unequalled fierceness."

German reports about the effect of naval bombardment were broadcast. These reports said that Allied naval fire was a "trump card." In a crisis, it was more accurate and could keep firing on target. It acted like a floating artillery unit. The reports also talked about the smaller Allied ships. They said these ships had firepower that should not be underestimated. A torpedo boat had the firepower of a howitzer battery. A destroyer had the firepower of an artillery battery. A cruiser was like an artillery regiment. Battleships with 38 to 40 cm guns had no equal in land warfare. They could only be matched by "an unusual concentration of very heavy batteries."

The German report said that Allied troops had a "particular advantage." This came from ship formations that could quickly move artillery to any point on the battlefield. Then they could change their position as needed. The Anglo-American naval forces made "the best possible use of this opportunity." A single coastal battery could repeatedly come under "quite extraordinary superior fire-power." Different types of warships would focus their fire on batteries when they were important in the fighting. This created an "umbrella of fire."

Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt said Allied naval gun fire support was "flexible and well directed." It helped the land troops, from battleships to gunboats. It was quickly mobile and always available artillery. It could be used to defend against German attacks or support Allied attacks. He added that it was skillfully directed by air and ground spotters. He also noted that Allied naval gunnery could fire quickly and accurately from a distance.

German batteries were not successful in sinking the Task Force's ships. Even though ships were hit and had near misses, they were not sunk. The moving ships could mostly stay in the cleared lanes. They used smoke, jammed German radar, and fired back effectively.

However, U.S. naval rules were changed after this operation. More attention was given to achieving effective long-range fire. According to Admiral Bertram Ramsay, if the German gunners had not had faulty ammunition, "they might well have caused heavy damage" to the Allied ships. Before June 1944, the U.S. Navy's main experiences were in the Mediterranean and Pacific. Naval historian Samuel Morison said these experiences led to the belief that modern U.S. ship fire control systems could easily defeat coastal batteries. But in the Mediterranean, shore batteries were not well-manned. Japanese coastal defense gunners were not well-trained.

Because of the Cherbourg operation, Morison concluded that even with modern aiming systems, a gun in a protected position is "exceedingly difficult for a rapidly maneuvering warship to destroy with a direct hit." However, many shells landing around the position would silence the guns temporarily. Admiral Deyo's report after the battle suggested that long-range bombardment with plane spotting would be needed to silence protected batteries. He stated that good air spotters or ground teams are needed for effective naval bombardment. This is especially true when strong currents add to the problems of ships under accurate shore battery fire.

Images for kids

-

USS Pheasant, minesweepers cleared lanes for battleship Texas, dispersed by casemated guns

See also

- Normandy landings

- Operation Overlord

- Battle of Cherbourg

- Battle for Caen

- Operation Cobra

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |