Lê Văn Duyệt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lê Văn Duyệt

黎文悅 |

|

|---|---|

Bronze statue of Lê Văn Duyệt in his tomb

|

|

| Born | 1763 or 1764 Trà Lọt, Hòa Khánh, Định Tường, Chiêm Thành |

| Died | 30 July 1832 (aged 68) Gia Định, Vietnam |

| Buried |

Tomb of Lê Văn Duyệt, Ho Chi Minh City

|

| Allegiance | Nguyễn lords Nguyễn dynasty |

| Years of service | 1789–1832 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Naval Battle of Thi Nai (1801) Battle of Quảng Nghĩa (1803) Cambodian rebellion (1811–1812) Campaign against Đá Vách (1816–1817) Cambodian rebellion (1820) |

Lê Văn Duyệt (1763 or 1764 – 30 July 1832) was a brave Vietnamese general. He helped Nguyễn Ánh, who later became Emperor Gia Long, win a big war. This war was against the Tây Sơn rebels. After winning, Nguyễn Ánh united Vietnam and started the Nguyễn dynasty.

Lê Văn Duyệt was born into a farming family. He joined Prince Nguyễn Ánh's army to fight the Tây Sơn. Because he was so good at fighting, he quickly became a top general. After the Nguyễn dynasty began in 1802, Duyệt became a very important government official, called a mandarin. He worked for the first two Nguyễn emperors, Gia Long and Minh Mạng.

Later, Duyệt became the viceroy of southern Vietnam. He ruled from Gia Định (which is now Saigon). His leadership helped the southern region, called Nam Bo, become rich and peaceful. Lê Văn Duyệt also disagreed with Emperor Minh Mạng on some important issues. He protected Christian missionaries and followers when the emperor wanted to stop them. This caused problems between Duyệt and Minh Mạng.

After Duyệt died, Emperor Minh Mạng ordered his tomb to be damaged. This made Duyệt's adopted son, Lê Văn Khôi, start a rebellion against the emperor. Later, other emperors, Thiệu Trị and Tự Đức, fixed Duyệt's tomb and honored him again.

Contents

Early Life of a Leader

Lê Văn Duyệt was born in 1763 or 1764. His family lived in Định Tường, which is now Tiền Giang Province. This area is in the Mekong Delta in southern Vietnam. His parents were simple farmers. Their family had moved south from central Vietnam a long time ago. Duyệt grew up in a poor family and used to herd buffaloes. His family later moved to Gia Định to find better opportunities.

General for Nguyễn Ánh

In 1780, Lê Văn Duyệt became a trusted helper for Prince Nguyễn Ánh. Nguyễn Ánh was 18 years old. His family, the Nguyễn Lords, had lost control of southern Vietnam to the Tây Sơn rebels in 1777. Nguyễn Ánh and his loyal followers had to hide in the jungles. Nguyễn Ánh soon made Duyệt a "Commander" of his bodyguards.

The war between the Tây Sơn and Nguyễn forces went back and forth for many years. In 1782, the Tây Sơn attacked Gia Định again. Nguyễn Ánh had to escape to Phú Quốc island with Duyệt's help. In 1787, Duyệt started leading his own army unit.

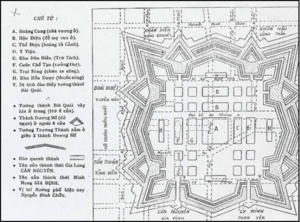

Things began to change for Nguyễn Ánh in 1788. A French Catholic priest, Pigneau de Behaine, helped him. The priest hoped Nguyễn Ánh would support his religion if he won. He found French military officers to fight for Nguyễn Ánh. In 1788, the Nguyễn forces took back Gia Định and kept it. Nguyễn Ánh then made Gia Định a strong fortress. He used it as his base to fight the Tây Sơn.

In 1789, Nguyễn Ánh made Duyệt a general. From then on, Duyệt fought alongside Nguyễn Ánh in many battles against the Tây Sơn. The fighting was fierce, especially near Nha Trang and Qui Nhơn. In 1801, Duyệt led a great naval victory at Thị Nại. This battle was a major turning point in the war. It showed that the Tây Sơn were starting to lose badly.

Later that year, Nguyễn Ánh attacked Phú Xuân, the Tây Sơn capital. The Nguyễn forces faced strong defenses. Nguyễn Ánh ordered Duyệt to lead his ships to attack from behind. Lê Văn Duyệt and his deputy, Le Chat, defeated the Tây Sơn army. This allowed the Nguyễn forces to capture Phú Xuân.

In 1802, Nguyễn Ánh declared himself Emperor Gia Long. He made Duyệt a top general and sent him to attack northern Vietnam. In October 1802, Duyệt captured the north. He renamed it Bắc Thành, meaning "Northern Citadel." This marked the final victory of the Nguyễn dynasty over the Tây Sơn. Duyệt's smart strategies and the French military help were very important for Nguyễn Ánh's success.

A High-Ranking Official

From 1802 to 1812, Duyệt was a high-ranking general in the new capital, Huế. In 1812, Emperor Gia Long made Duyệt the viceroy of Gia Định. This meant Duyệt was in charge of southern Vietnam and even Cambodia.

The viceroy had a lot of power. He could make decisions about lawsuits and choose officials. Emperor Gia Long trusted Duyệt and other leaders from the south. This helped Duyệt gain strong support from the local people. He also welcomed Chinese refugees and former rebels into government jobs if they were skilled. This helped bring more people into society.

In 1812, a prince in Cambodia tried to take the throne with help from Siam (Thailand). The Cambodian king had to flee to Gia Định. In 1813, Duyệt led 10,000 troops into Cambodia. He forced the Siamese army to leave. Duyệt helped the Cambodian king get his throne back. He also built two forts in Cambodia to show Vietnam's control. This made Cambodia a protectorate, meaning it was protected and influenced by Vietnam.

Duyệt's rule made southern Vietnam stable and prosperous. People called him Cọp Gấm Đồng Nai, meaning "White Tiger of Đồng Nai". As Gia Long's most trusted official, Duyệt often talked with European traders and visitors.

In 1815, Emperor Gia Long called Duyệt back to help stop rebellions in central Vietnam. In 1819, Duyệt was in northern Vietnam, putting down more revolts. During this time, he met a former rebel leader from the mountains. This man became Duyệt's adopted son, named Lê Văn Khôi. Khôi later got an important job in Gia Định.

When Emperor Gia Long was dying, Duyệt was one of only two people with him. Gia Long trusted Duyệt so much that he gave him command of five royal army groups.

After calming central Vietnam, Duyệt became viceroy of southern Vietnam and Cambodia again in 1820. This was under the new emperor, Minh Mạng. The emperor gave Duyệt even more power. Duyệt could now control all foreign trade in his area. He could also collect taxes in Cambodia and on goods coming in and out. This gave Duyệt control over the rich resources of the south, like farming land and timber. The south was growing fast with new Vietnamese settlers.

Duyệt stopped a revolt by local Khmer people and added many new taxpayers. He also oversaw the repair of the Vĩnh Tế Canal, a very important waterway. Duyệt was great at keeping order and increasing trade. His work made southern Vietnam a rich and peaceful place. Emperor Minh Mạng rewarded Duyệt with a special jade belt and arranged for a princess to marry Duyệt's adopted son.

Challenges with Emperor Minh Mạng

There was often tension between Duyệt and Emperor Minh Mạng. Emperor Gia Long had used European help to win the war. He allowed missionaries to work in Vietnam. But he also followed traditional Vietnamese ways. He was worried when his son, Prince Cảnh, became Catholic and did not respect ancestor worship.

Prince Cảnh died, so Gia Long chose his other son, Nguyễn Phúc Đảm (Minh Mạng), to be the next emperor in 1816. Gia Long chose Minh Mạng because he was strong and did not like Western ways. He told Minh Mạng to be polite to Europeans but not give them too much power.

Minh Mạng did not like Duyệt. Duyệt was one of many high-ranking officials who did not agree with Minh Mạng becoming emperor. Duyệt and his southern friends often supported Christianity. They wanted Prince Cảnh's family to rule. Because of this, Catholics respected Duyệt a lot.

Historians believe Duyệt wanted a weaker emperor. This would let him keep more power in the south. Duyệt was a military man, not a scholar. He cared more about getting weapons from Europeans than about traditional rules.

Minh Mạng started to limit Catholicism. He said it was a "wrong teaching." He worried that Catholics would cause problems, especially as more missionaries arrived.

Duyệt protected Vietnamese Catholics and Westerners. He did not follow Minh Mạng's orders to stop them. Duyệt wrote to Minh Mạng, reminding him that missionaries had helped them when they were hungry. Minh Mạng had ordered missionaries to move to the capital, saying he needed translators. But he really wanted to stop them from spreading their faith. Officials in other parts of Vietnam obeyed, but Duyệt did not. So, Christians in the south could still practice their faith openly.

Duyệt also disagreed with Minh Mạng about how to treat criminals and former rebels. Many rebels were captured during the early years of the Nguyễn dynasty. They were often sent to southern Vietnam. Duyệt had pardoned some of these rebels and given them jobs. He wanted to continue this policy to help develop the south. But Minh Mạng disagreed. He thought it was wrong to give power to former criminals.

Duyệt also had good relations with the Chinese community in southern Vietnam. He even adopted a Chinese merchant as his son. He gave this son special favors, like a job in trade. Duyệt wanted to give tax breaks to poor Chinese immigrants to encourage them to settle and help the region grow. Minh Mạng was unsure about this. He thought it would be hard to know who was truly poor.

Minh Mạng tried to stop Chinese merchants from trading by sea in 1827. But the merchants easily found ways around this. They used their connections with Duyệt and fake registrations. Minh Mạng could only stop this illegal trade after Duyệt died.

For a while, Duyệt's power in the south forced Minh Mạng to be less strict about Christianity. But it also made the tension between them worse. Minh Mạng wanted to reduce Duyệt's power. He slowly started to remove Duyệt's close helpers from their jobs.

In 1821, Minh Mạng sent two officials from Huế to the south. They were supposed to oversee education and choose new government officials. But Duyệt's officials stopped them. They went back to the capital two years later, having failed.

In 1823, one of Duyệt's close helpers was accused of illegal rice trading. Duyệt stopped the investigation and angrily demanded that the accuser be punished. A few years later, Duyệt's helper was moved to northern Vietnam and put in prison. Duyệt could not do anything about it. Minh Mạng put one of his own men in that position.

In 1826, Duyệt resisted when the emperor tried to remove a local official. Minh Mạng criticized him, saying that only the capital could appoint officials. The next year, Duyệt executed criminals without telling the capital. Minh Mạng criticized him again, saying that only the court could decide matters of life and death.

In 1829, Duyệt lost another ally. This was Nguyen Van Thoai, who ran Cambodia for him. Duyệt wanted to appoint another helper, but Minh Mạng chose one of his own officials instead. Minh Mạng then made this official a minister, putting him above Duyệt in power. This made Duyệt less important in Cambodia.

In 1831, just before Duyệt died, Minh Mạng started to break up Duyệt's army. He sent parts of it to other areas of Vietnam. He also sent a loyal general to Gia Định to reduce Duyệt's power. Also, no government reports from the south could be sent to the capital without being approved by Minh Mạng's civil officials. These actions made the local people in the south feel more angry and separate.

Family and Personal Life

Lê Văn Duyệt had a wife named Đỗ Thị Phận. Besides Lê Văn Khôi, he had another adopted son named Lê Văn Yến. Lê Văn Yến married Princess Ngoc Nghien, a daughter of Emperor Gia Long.

People usually described Duyệt as a serious and quick-tempered man, but also fair. This made people both fear and respect him. Some later stories said he was too strict. He was also seen as a bit unusual. He had 30 mountain people as servants. He also kept exactly 100 chickens and 100 dogs at his home. When he came home, he would have a tiger and 50 dogs walk behind him.

In 1825, a French visitor named Michel-Duc Chaigneau said Duyệt was very talented in both fighting and ruling. He said people feared Duyệt but also loved him because he was fair.

Duyệt loved cockfighting, hát bội (Vietnamese classical opera), and court dancing. These were popular with common people in the south. He reportedly joked with Emperor Gia Long about how much he loved cockfighting. He would sometimes beat a drum to encourage opera performers. He also supported local folk religions that honored goddess spirits.

A British visitor in 1822, George Finlayson, said Duyệt dressed simply, like a farmer. Finlayson described Duyệt as intelligent, with a round, soft face and no beard. He said Duyệt's voice was high-pitched, like an old woman's.

Duyệt's informal style caused problems with Emperor Minh Mạng. Minh Mạng's government was more focused on strict traditional rules. Younger officials thought Duyệt and his southern group were uncultured. Older military officials felt less comfortable in the court over time. Emperor Gia Long was direct, but Minh Mạng was more vague. This was because Gia Long had to be direct during the war, while Minh Mạng grew up with scholars.

After visiting the capital in 1824, Duyệt felt uncomfortable. He told a friend that he and other military leaders were too direct for the new court. He suggested they resign to avoid mistakes. Duyệt and General Le Chat did offer to resign, but the emperor refused. Duyệt wanted a job in the capital, but he was not given one. Some in the court worried he might try to take power. So, Duyệt was sent back to southern Vietnam, far from the capital.

Death and Lasting Impact

Lê Văn Duyệt died on July 30, 1832, in the Citadel of Saigon. He was 68 years old. He was buried in Bình Hòa, Gia Định, which is now Ho Chi Minh City. Local people called his tomb Lăng Ông Bà Chiểu, meaning "Tomb of the Marshal in Ba Chieu."

Duyệt's death allowed Minh Mạng to fully put his policies into action in the south. The emperor ended the position of viceroy, making Duyệt the last one. He put the south under his direct control. New officials arrived and investigated Duyệt and his helpers. They reported that Duyệt had been corrupt.

Because of this, Minh Mạng ordered Duyệt's tomb to be damaged after his death. Sixteen of Duyệt's relatives were executed, and his friends were arrested. This made Duyệt's adopted son, Lê Văn Khôi, escape from prison. On May 10, 1833, Khôi started a rebellion against the emperor.

The rebellion lasted three years and was supported by Siam. After it was put down, Minh Mạng again ordered Duyệt's tomb to be damaged. The tomb stayed in bad condition until the next emperor, Thiệu Trị, took over. Thiệu Trị honored Duyệt again and fixed his tomb. Later, Emperor Tự Đức made the tomb a national monument.

Even after the French took control of southern Vietnam, Duyệt was still honored. His yearly celebrations were attended by politicians. There was even a legend that Duyệt appeared in the dreams of Nguyen Trung Truc, a fisherman who fought the French. Duyệt supposedly advised him on how to fight. In 1937, Duyệt's tomb was renovated with donations.

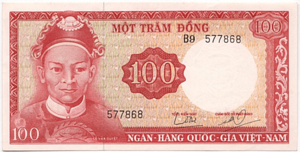

Under the government of South Vietnam, Duyệt was seen as a great national hero. His picture was on banknotes, and streets were named after him. However, the current Vietnamese Communist Party government did not honor Duyệt for a long time. They saw him as someone who helped the French gain influence. After the fall of Saigon in 1975, Duyệt's tomb was not maintained, and streets named after him were renamed. This changed in 2008, when the government renovated his tomb and allowed a play about his life to be performed.

Today, many people in southern Vietnam still see Lê Văn Duyệt as their most important local hero. People in Ho Chi Minh City, no matter their background or religion, greatly respect him. His beautiful shrine is a special place for them.

|

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |