Manning Johnson facts for kids

Manning Rudolph Johnson (born December 17, 1908 – died July 2, 1959) was an African-American leader in the Communist Party USA. He even ran for a spot in the U.S. House of Representatives for New York in 1935. Later, he left the Party and became a government informant and witness, sharing information about communist activities.

Contents

Early Life

Manning Rudolph Johnson was born in Washington, D.C. He went to elementary, junior high, and high school there. He also graduated from the Naval Air Technical School.

In 1932, Johnson attended a special "secret school" for three months. This school was part of the Workers School in New York. It was designed to train people to become "professional revolutionists" or active members of the Communist Party. The school was free, and all expenses were paid.

Career

Joining the Communist Party

From 1930 to 1939, Manning Johnson was a member of the Communist Party USA. He left the party shortly after the Hitler-Stalin Pact was announced in 1939.

During his time in the party, he worked as a national organizer for the Trade Union Unity League. He also served as a district leader in Buffalo, New York, from 1931 to 1934. In 1935, he ran as a Communist Party candidate for Congress. From 1936 to 1939, he was part of the Party's National Committee. He also served on the National Trade Union Commission and the Negro Commission.

Johnson later said he left the Communist Party for several reasons. He disagreed with the Party's idea of creating a "Soviet Negro Republic" in the Southern United States. He also felt the Party was not sincere in helping the Scottsboro Boys, a group of young Black men wrongly accused of a crime. The final reason he left was the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939, which was an agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union.

Becoming an Anti-Communist Witness

After leaving the Communist Party, Johnson said that communists tried to stop him from working in non-communist labor groups. During World War II, he served in the United States Navy.

By 1950, Johnson had testified as a government witness in many cases, helping the government understand communist activities. In 1947, he first testified against a man named Gerhart Eisler.

In 1948, Johnson testified before the Canwell Committee in Washington state. He claimed that a professor named Melvin Rader was a communist.

In 1949, Johnson worked as a representative for the Retail Clerks' International Association, a large union.

On July 14, 1949, Johnson testified about how communists tried to influence minority groups. He explained the Communist Party's plan to create an independent "Soviet Negro Republic" in the Southern "Black Belt" region of the U.S. He said the Party wanted this republic to break away from the U.S., even by force if needed. However, Johnson noted that most Black people who joined the Party did not understand this part of the plan.

He also talked about the National Negro Congress (NNC), which was meant to help Black Americans. Johnson said that the NNC became controlled by communists, causing its non-communist leader, A. Philip Randolph, to quit.

Johnson also criticized the Party's handling of the Scottsboro Boys case. He said the Party tried to remove the boys' lawyer, Samuel Leibowitz. He also made strong statements against communism, saying things like, "Human life, to Communists, is cheap." He praised the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), saying their work was "remarkably fine."

Johnson also testified against famous singer and activist Paul Robeson. He claimed Robeson was a secret member of the Communist Party. Johnson said party members were told not to reveal Robeson's membership because his role was very secret. In 1949, Johnson said it was "regrettable" that Robeson had "sold himself to Moscow."

In December 1949, Johnson was a witness in the trial of union leader Harry Bridges. Johnson said he had seen Bridges at a secret Communist Party meeting in 1936. This testimony hurt Bridges' case because he had denied being a Communist Party member.

In 1950, Johnson testified against the International Workers Order, another organization he claimed was influenced by communists.

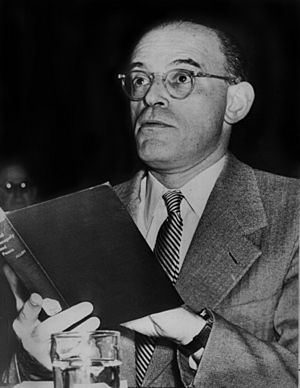

In 1953, Johnson testified before the U.S. House of Representatives' Committee on Un-American Activities. He was asked if deceit was a major part of communist activities. Johnson replied that communists used "fine gestures and honeyed words" to trick people, leading them to "moral decay" and "spiritual slavery."

In May 1954, Johnson testified against Ralph Bunche, a diplomat, before a government loyalty board.

However, Johnson's honesty was questioned by some. In 1954, Professor Melvin Rader wrote an article called "The Profession of Perjury," saying that Johnson's testimony against him was false. Rader noted that even though facts proving Johnson's dishonesty were known, he continued to work for the Justice Department as a witness.

In 1955, the Supreme Court of the United States agreed that some claims made by Johnson and another witness, Paul Crouch, were false. A Soviet newspaper, Pravda, even listed Johnson as an FBI informant who received money for his testimony.

Changing Views on the NAACP

While testifying for Congress in 1949, Johnson spoke positively about the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He said their work was "remarkably fine."

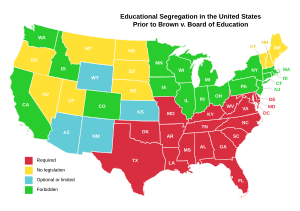

However, in his later years, Johnson's views on the NAACP changed. In a recorded speech, he criticized the NAACP for collecting "millions of dollars through racial incitement." He also attacked the NAACP's support for racial integration. He said that the integration of schools was a "Pyrrhic victory" (a victory that comes at too great a cost).

Johnson also criticized the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision by the Supreme Court, which ruled that separate schools for Black and white students were unconstitutional. He believed this decision made things worse for Black students in the South because it removed the responsibility of Southern states to make schools equal. He felt that the Supreme Court had "opened the Pandora's box" and set back race relations by 50 years.

Johnson often linked racial unrest to communist influence. He said, "Beneath all of the racial unrest, at the root of all racial unrest in the country, is the clammy, cold, bloody hand of Communism."

Personal Life and Death

A 1949 Time magazine article described Johnson as a "husky, big-jawed... smooth, deep-voiced Negro."

In the late 1930s, Johnson was a member of the American League Against War and Fascism. He also knew the poet Claude McKay very well.

Manning Johnson died on July 2, 1959, after a car accident that happened near Lake Arrowhead, California. He is buried in Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego, California.

Legacy

In 1966, W. Cleon Skousen called Johnson "the most important Negro Communist in the United States."

In 1981, Victor S. Navasky wrote about Manning Johnson admitting in 1951 that he would lie under oath if it helped his government. Johnson reportedly said, "If the interests of my government are at stake... I say I will do it a thousand times."

Works

Manning Johnson wrote several works, including:

- "Party Organizer" (1933)

- "An American Holiday" (1939)

His book, Color, Communism, and Common Sense, was used in a 1969 film lecture. In the book, Johnson claimed that the Communist Party USA was controlled by the Soviet Union. He also claimed that Gerhart Eisler was the Soviet Union's main representative in the U.S.

In his book, Johnson said that the Communist Party controlled many unions and organizations, including the National Negro Congress and the Sharecroppers' Union.

See also

In Spanish: Manning Johnson para niños

In Spanish: Manning Johnson para niños

- Communist Party USA

- Anti-Communism

- Harry Bridges

- Paul Robeson

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |