March of Intellect facts for kids

The March of Intellect was a big debate in England during the early 1800s. It was also called the 'March of mind'. Some people were excited about society becoming smarter and more knowledgeable. They welcomed new ideas and progress. Others worried about these changes. They thought people were too obsessed with new ideas and moving forward too fast.

This debate showed how much British society was changing. Factories were growing (the Industrial Revolution), more people wanted a say in government (democracy), and social classes were shifting. Some people liked these changes, and some did not.

Contents

The Start of the Idea

Education for Everyone

The idea of the March of Intellect began when more people started getting an education after 1800. This included children and working-class people. In 1814, the term 'march of Mind' was first used in a poem. It was written by Mary Russell Mitford for the Lancastrian Society. This group helped bring education to children. The main church also started working to educate children.

New Kinds of Knowledge

The March of Intellect was part of bigger discussions in the 1800s about how knowledge was shared. Before, "polite learning" was popular. This meant rich people studied old cultures. But people like Jeremy Bentham said this kind of learning wasn't very useful.

The Industrial Revolution changed things. People started focusing on "useful knowledge." This was about practical things, especially science. Many people, especially liberal Whigs, believed useful knowledge was the way forward. But they didn't always agree on what "useful" meant.

Books and Reading

From the late 1700s, there were more magazines, encyclopedias, and books. This made people wonder about how easily knowledge was available. It also became cheaper to print books. A book that cost 10 shillings (a lot of money) in the early 1800s could cost half that by the 1820s.

More people started reading. There were more coffee houses where people could talk and read. Also, Mechanics' Institutes started in 1823. These places taught working people about science and technology. Literary and Philosophical Societies also grew. All these things changed how adults read and learned.

Education for the Working Class

Working-class people often couldn't read well. Books were also very expensive for them. Some events, like the Peterloo Massacre, made rich people worried about protests. They didn't want to educate the lower classes because they feared it would lead to more unrest.

However, some conservatives thought educating the working class could help control them. They believed education would teach working people their place in society. This would stop political problems.

Liberal Whigs, like Henry Brougham, had a different view. They followed Bentham's utilitarian idea. This idea was about making "the greatest happiness for the greatest number" of people. They thought science was important for working-class people. They debated the best ways to share this knowledge.

The Height of the Debate

Progress and New Ideas

The March of Intellect was talked about most in the 1820s. One group, called the Philosophic Whigs, led by Henry Brougham, saw a bright future. They believed society was moving forward. A writer named Thackeray even mentioned how radicals (people who wanted big changes) often used phrases like 'the March of Intellect'.

Brougham started the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. This group aimed to spread practical information. He also helped create University College, London. These actions seemed to show the new progress of the time.

Making Fun of Progress

But conservatives saw the March of Intellect as everything they disliked. They didn't like new ideas, machines, widespread education, or social unrest. They made fun of the 'March' in many ways.

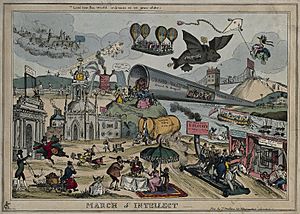

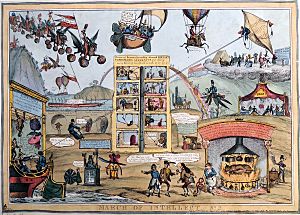

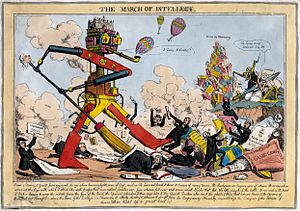

The March of Intellect was often made fun of in satirical writings and cartoons. Cartoons were a popular way to talk about current events in the 1800s. They became very common during this time.

William Heath drew many famous cartoons between 1825 and 1829. He used machines and steam-powered vehicles in his drawings. He made fun of the liberal Whigs' idea that education could solve all problems. His cartoons showed funny future visions. For example, they showed how technology might fix travel or mail delivery. These drawings showed that society was changing. But they also made people wonder if these changes would be good or bad.

For example, Robert Seymour's cartoon called 'The March of Intellect' (around 1828) showed a giant robot sweeping away problems. These problems included fake doctors and slow court cases. This cartoon could be seen as a bit scary in its attempt to "fix" society. Satire about the March of Intellect often criticized the idea of educating the working class.

In Peacock's 1831 book Crotchet Castle, a character made fun of the "Steam Intellect Society." He linked the march to foolishness and crime. He joked that "the march of mind...marched in through my back-parlour shutters, and out again with my silver spoons."

Later Views

After a lot of changes, including the Great Reform Act and the growth of railways, the idea of progress became widely accepted. People still had concerns, but they focused on making the changes better, not stopping them. Some thinkers worried that too much education might make people less strong or moral. Poets tried to keep people's unique qualities safe from the "useful" way of thinking.

See also

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |