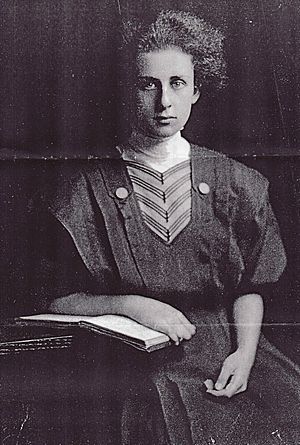

Martha Gruening facts for kids

Martha Gruening (1889–1937) was an American journalist, poet, and activist. She fought for civil rights and women's right to vote. Martha believed that gender, race, and social class were all connected. Her writings and research for the NAACP helped advance the civil rights movement. She also worked to include women of color in the fight for women's suffrage.

Early Life and Education

Martha Gruening was born in Philadelphia in 1889. She was one of five children. Her father was a doctor who encouraged talks about fairness and equality at home. As a Jewish woman, she faced some discrimination. However, she was lucky enough to go to college.

She attended the Ethical Culture School in New York. This school matched her family's modern ideas. In 1909, she graduated from Smith College, a women's college. There, she started a student group for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). This group worked to get women the right to vote. She later left NAWSA because they refused to let a Black delegate join their meeting in 1912.

Martha's passion for education grew after she joined the Philadelphia Shirtwaist Strike (1909-1910). Women workers went on strike because they wanted better pay and working conditions. Martha supported women's rights and joined the protests. She was arrested for picketing. In court, she explained she was checking if police were arresting workers fairly. The judge told her that people "of your class" were causing trouble. This showed Martha how women were treated unfairly.

After her arrest, Martha was sent to Moyamensing Prison. She later wrote about her experiences there. Her writings about the prison helped reformers push for changes. What she learned about police, the law, and money problems inspired her. She also saw the power of journalism. After working as a freelance writer and traveling for the women's suffrage movement, she studied law at New York University in 1914. It was very rare for a woman to have so much education at that time.

Important Works

Martha Gruening's poems showed her modern social views. Before the U.S. joined World War I, there was a campaign to make the military stronger. This was called the Preparedness Campaign. The Masses magazine asked writers to share their thoughts on patriotism. Martha wrote a poem called Prepared. In it, an American speaker thinks about freedom and decides that violence is okay to defend it. Gruening's poem suggested that true patriotism means promoting liberty and justice, not just showing off.

During the Harlem Renaissance, many famous people shared their ideas about Black culture. In her essay Negro Renaissance (1932), Martha Gruening wrote about the movement. She felt it had made progress but was also "exploited commercially." She mentioned Alain Locke's idea of a "common consciousness." Gruening thought the Harlem Renaissance had more individual works. She also praised Langston Hughes's Not Without Laughter and Willa Cather's My Antonia. She wrote that these stories showed everyday life for Black families. They were not just about race but also about universal experiences.

Gruening was also well known for her work with the NAACP and The Crisis magazine. She was good friends with the editor, W. E. B. Du Bois. They both believed in social equality. They also criticized the women's suffrage movement for not including Black women. W.E.B. Du Bois praised Gruening for fighting for women of color.

In her article "Two Suffrage Movements," Martha Gruening said the suffrage movement started because of the movement to end slavery. She argued that women could not fight for enslaved people's freedom without also fighting for their own. She saw that both enslaved people and white women lacked rights and education. Gruening believed that everyone, no matter their race or gender, should understand that "the disenfranchised of the earth have a common cause."

Gruening's essay "With Malice Afterthought" was published in The Forum (American magazine) in 1916. In this essay, she strongly argued against the death penalty.

Martha Gruening was an assistant secretary for the NAACP. She wrote reports on national events. Her research on lynchings in the United States was very important for the NAACP. With help from Helen Boardman, Gruening collected data for the NAACP's first book, Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States 1889-1918. They manually gathered information on thousands of lynchings. This book and Gruening's research helped raise awareness about the terrible violence of lynchings.

Gruening also wrote many book reviews. In her review of Theodore Stanton’s The Life and Letters of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1922), Gruening praised Stanton's strength. She also noted Stanton's presence at the World Anti-Slavery Convention. This event was important for the anti-slavery movement. It also showed Stanton the need for "the emancipation of women" because women delegates were excluded. Gruening also felt that Black women should be part of the women's movement. She mentioned Stanton's question about the Fourteenth Amendment: "Is the African race composed entirely of males?" Gruening added that this question is still relevant today.

Legacy

Martha Gruening studied and wrote about modern education in Europe. In 1917, she adopted a young African American boy named David Butt. She raised him as a single mother, facing challenges from society and money problems. She wanted to start a special school where all children, no matter their race or background, could get an education. Sadly, the school did not work out, and David Butt died young at age twenty-five.

After her son's death, Martha continued to fight for the civil rights of African Americans. She died on October 28, 1937, at age 48, from a brain aneurysm. Her work for the NAACP and her fight for the rights of others define her lasting impact.

Gomez Mill House

In 1918, Martha Gruening bought the Gomez Mill House. This was three years after she adopted David Butt, a young African American boy. She wanted to give him a good education. She planned to set up the Mill House as a "Libertarian International School." It was meant to educate children of all races. Martha supported modern European ways of teaching. She worked with Helen Boardman, who also collaborated with the NAACP. While the school was listed in a 1921 almanac, there is no clear proof it ever opened to the public. Later, Gruening allowed Helen Boardman to sell the Gomez Mill House in 1923.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |