Maso Finiguerra facts for kids

Maso Tommasoii Finiguerra (1426–1464) was a talented Italian goldsmith from Florence. He also created art using a special metalworking technique called niello. Besides that, he was a skilled draftsman (someone who draws) and an engraver.

For a long time, people thought Maso Finiguerra invented engraving as a way to make prints. This idea came from a famous writer named Giorgio Vasari. Because of this, Maso was seen as a very important person in the history of old master prints. However, later on, experts realized that Vasari was mistaken. Engraving actually started in Germany before it came to Italy.

Vasari only mentioned that Maso made paper copies of his niello artworks. He didn't say Maso made engravings from special printing plates, which is how we usually think of engravings. In fact, Maso probably never made such engravings. Even though he was an important artist, not many of his original works or prints have survived. This is why experts don't study him as much today. Still, over 100 drawings in the Uffizi gallery and other places are believed to be by him.

Maso Finiguerra died when he was in his late thirties. His artistic style influenced other early Florentine engravers and artists who made drawings. One of these was Baccio Baldini, whom Vasari also linked to Maso.

Contents

Maso's Career and Artworks

Maso was born in Florence in 1426. His father and grandfather were both goldsmiths, so he grew up in a family of artists. He worked with them and quickly became known for his amazing work in niello. Niello is a technique where a black mixture, usually of sulfur, copper, silver, and lead, is used to fill designs engraved on metal. This creates a strong contrast.

In 1449, a record shows that a sulfur copy of one of his niello pieces was used as payment for a dagger. In 1452, Maso was paid for a silver niello pax (a small religious image). This pax was ordered for the Florence Baptistery by a powerful merchant group called the Arte di Calimala.

By 1457, Maso started his own business with another goldsmith, Piero di Bartolommeo di Sail. They even worked with the famous artist Antonio del Pollaiuolo. In 1459, some of Maso's artworks were noted as belonging to Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai, a wealthy person, at the Palazzo Rucellai. Later, in 1462, Maso supplied fancy waist buckles, forks, and spoons to another rich Florentine, Cino di Filippo Rinuccini.

In 1463, Maso drew large designs, called cartoons, for the sacristy (a room in a church) of Florence Cathedral. These designs were for five or more figures. Another artist, Alessio Baldovinetti, colored the heads in Maso's drawings. These figures were then made into intarsia, which is a type of wood inlay art. Maso Finiguerra made his will on December 4, 1464, and passed away soon after.

Works We Still Have Today

The only works we know for sure are by Finiguerra are the intarsia figures for the Florence Cathedral sacristy. These figures are more than half life-size. However, some experts think they look so much like the work of Antonio del Pollaiuolo that it's hard to be sure Maso designed them himself.

Still, many other artworks are believed to be by him. These include a few niello pieces, sulfur copies made from them, and over a hundred drawings.

His Drawings

Most of Maso's drawings are kept at the Uffizi gallery. Some of them have "Maso Finiguerra" written on them from the 1600s, likely by a curator named Filippo Baldinucci. These drawings show many people from his workshop and the streets of Florence. They seem to be drawn directly from real life. Maso used these drawings to quickly come up with ideas for his art. The Uffizi collection also has 14 studies of birds and animals, including a rather fancy cockerel.

There are two large drawings on vellum (a type of treated animal skin) that show scenes from the Old Testament. They are full of many figures. One is Moses on Mount Sinai, and the Brazen Serpent below at the British Museum. The other is The Flood at the Kunsthalle, Hamburg. These drawings were probably meant to be finished artworks. Later, another artist, Francesco Rosselli, copied them as engravings.

Experts believe these drawings were made between the 1450s and Maso's death in 1464, based on their style and the clothing shown. They match what Vasari and Baldinucci wrote about Finiguerra's drawings. Also, some figures from his Uffizi drawings appear in rare niello prints from Florence at that time. This suggests he might have been an engraver in niello.

The Florentine Picture-Chronicle, a collection of drawings, was first thought to be by Finiguerra when it was published in 1893. However, it is now more often believed to be by Baccio Baldini or someone in his art group. This album was a unique and big project to create a "picture story of the world," but it was never finished. The drawings were made with black chalk, ink, and often a wash (a thin layer of paint).

Nielli and Casts

It's tricky to say for sure which niello pieces are by Maso, especially those at the Bargello museum. This is because we have to match old records and comments from artists like Vasari and Benvenuto Cellini with the artworks that still exist.

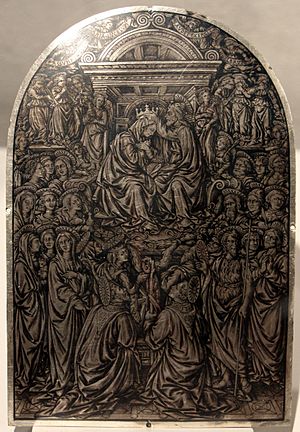

As mentioned, in 1452, Maso made a niello silver pax for the Florence Baptistery. In 1455, the merchant group ordered a second pax from another goldsmith, Matteo Dei. We don't know what scenes were on these paxes from the records. Two paxes with similar frames at the Bargello museum are thought to be from the baptistery. However, their styles are so different that they probably weren't made by the same artist. One, showing the Coronation of the Virgin, is generally thought to be of higher quality and is believed to be by Finiguerra. The other shows a Crucifixion and is often thought to be Dei's work from 1456.

The confusion comes from Cellini praising a Finiguerra pax with a Crucifixion scene that included horses. Vasari also praised one with scenes from the Passion of Christ. Experts try to match other surviving paxes to these descriptions while making sure they all have a similar style. Some of the nielli also have surviving sulfur casts, which can help link them to Finiguerra.

Maso's Lasting Influence

Other writers also praised Maso Finiguerra. His friends, like the Florentine artist Filarete and the poet A.M. Salimbeni from Bologna, admired his niello work. Later, Baccio Bandinelli said Finiguerra was one of the young artists who worked with Lorenzo Ghiberti on the famous bronze doors of the Baptistery, Florence.

Benvenuto Cellini believed Maso was the best niello engraver of his time. Cellini said Maso's best work was a Crucifixion pax in the baptistery of St. John. He also noted that Maso wasn't a great draftsman on his own. So, for many of his works, including the famous pax, he used drawings made by Antonio del Pollaiuolo.

Vasari's stories about Maso were supported by Baldinucci in the next century. Baldinucci said he saw many drawings by Finiguerra that looked like the style of Masaccio. He also added that Maso lost a competition to Pollaiuolo for a large silver altar-table commission. This famous altar is now in the Opera del Duomo in Florence.

Old Claims About His Invention

In the late 1700s, it seemed like Vasari's idea that Finiguerra invented engraving was proven true. There was a beautiful 15th-century niello pax of the Coronation of the Virgin in the Florence Baptistery (now at the Bargello). An art expert named Abate Gori thought it might be by Finiguerra. Later, another expert, Abate Zani, found a sulfur copy of the exact same niello in a private collection. Then, he found a paper print of it in a library in Paris. Zani excitedly announced that this was proof of Finiguerra's invention and Vasari's accuracy.

However, serious art historians today no longer believe Zani's famous discovery. First, the art of printing from engraved copperplates was already known in Germany and Italy years before Finiguerra's supposed invention. Second, if Cellini was right, Finiguerra's pax for the baptistery showed a Crucifixion, not a Coronation of the Virgin. Also, the recorded weight of Finiguerra's pax doesn't match the one Gori and Zani claimed was his.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, all reliable records show that Finiguerra worked very closely with Antonio del Pollaiuolo. Pollaiuolo and his group had a very distinct style. The style of the Coronation pax, however, looks completely different. The artist who designed it must have learned from a different art school, likely the one led by Filippo Lippi.

See also

In Spanish: Maso Finiguerra para niños

In Spanish: Maso Finiguerra para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |