Benvenuto Cellini facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Benvenuto Cellini

|

|

|---|---|

Bust of Benvenuto Cellini on the Ponte Vecchio, Florence

|

|

| Born | 3 November 1500 Florence, Republic of Florence

|

| Died | 13 February 1571 (aged 70) Florence, Grand Duchy of Tuscany

|

| Resting place | Santissima Annunziata, Florence |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Accademia delle Arti del Disegno |

| Known for | Goldsmith, sculptor, author |

|

Notable work

|

Cellini Salt Cellar |

| Movement | Mannerism |

Benvenuto Cellini (/ˌbɛnvəˈnjuːtoʊ tʃɪˈliːni, tʃɛˈ-/, Italian: [beɱveˈnuːto tʃelˈliːni]; 3 November 1500 – 13 February 1571) was a famous Italian goldsmith, sculptor, and writer. He lived during the Renaissance period. Some of his most well-known creations include the Cellini Salt Cellar, the sculpture of Perseus with the Head of Medusa, and his own life story, which is considered a very important book from the 1500s.

Contents

Benvenuto Cellini's Life Story

Early Years and Training

Benvenuto Cellini was born in Florence, which is in modern-day Italy. His parents were Giovanni Cellini and Maria Lisabetta Granacci. Benvenuto was their second child. His father was a musician and made musical instruments, and he wanted Benvenuto to follow in his footsteps.

However, when Benvenuto was fifteen, his father finally agreed to let him become an apprentice to a goldsmith named Antonio di Sandro. By the age of 16, Benvenuto was already getting noticed in Florence. He had to leave Florence for six months after an argument with some friends.

He went to Siena, where he worked for another goldsmith. From Siena, he moved to Bologna. There, he became a better player of the cornett and flute, and he also improved his goldsmithing skills. After visiting Pisa and spending time back in Florence, he moved to Rome when he was nineteen.

Working in Rome

In Rome, Benvenuto's first projects included a silver casket, silver candlesticks, and a vase for the bishop of Salamanca. These works impressed Pope Clement VII. Another famous piece from this time is the gold medallion of "Leda and the Swan". This medallion is now in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence. He also played the cornett again and became one of the pope's court musicians.

During an attack on Rome by the forces of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Cellini showed great courage. He later wrote that he shot and injured a prince named Philibert of Châlon. His bravery helped him make peace with the officials in Florence, and he soon returned home.

Back in Florence, he focused on making medals. Two famous ones are "Hercules and the Nemean Lion" (made of gold) and "Atlas supporting the Sphere" (also gold). The "Atlas" medal eventually belonged to Francis I of France.

Cellini then traveled to the court of the duke of Mantua before returning to Florence, and then to Rome again. In Rome, he worked on jewelry and made dies for coins for the papal mint. In 1529, his brother was killed. Cellini later killed the person responsible. He then fled to Naples to avoid trouble. With help from some important church leaders, Cellini received a pardon. He also found favor with the new pope, Paul III.

Time in Ferrara and France

After some disagreements, Cellini left Rome for Florence and Venice. When he was 37, after visiting the French court, he was put in prison. He was accused of taking valuable gems from the pope's tiara during a war, but this was likely a false charge. He was held in the Castel Sant'Angelo. He escaped but was caught again and treated very harshly.

While in prison in 1539, someone tried to harm him by putting diamond dust in his food, but it didn't work because a different gem was used. With the help of important people, especially a cardinal from Ferrara, Cellini was finally set free. He gave the cardinal a beautiful cup as a thank you.

Cellini then worked for King Francis I at Fontainebleau and Paris. He faced many challenges and had rivals at the French court.

Return to Florence and Later Life

After several years of creating art in France, Cellini returned to Florence. He was welcomed by Duke Cosimo I de' Medici, who made him a court sculptor. The Duke gave him a nice house and a good salary. Cosimo also asked him to create two important bronze sculptures: a bust of himself and Perseus with the Head of Medusa. This famous statue was meant for the Lanzi loggia in the city center.

During a war with Siena in 1554, Cellini helped strengthen Florence's defenses. Even though he sometimes felt unfairly treated by the Duke, his amazing artworks continued to impress the people of Florence. During this time, he had a strong rivalry with another sculptor named Baccio Bandinelli.

In 1562, he married Piera Parigi. They had five children, but only a son and two daughters lived past childhood.

On January 13, 1563, he became a member of the important Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence. He died in Florence on February 13, 1571, and was buried with a grand ceremony in the church of the Santissima Annunziata.

Cellini's Artworks

Large Sculptures

Besides his work with gold and silver, Cellini also made larger sculptures. One of his main projects in France was likely the Golden Gate for the Château de Fontainebleau. Only the bronze part of this unfinished work, which shows the Nymph of Fontainebleau (now in the Louvre Museum), still exists. We know what the whole gate looked like from old drawings and records.

When he returned to Florence in 1545, Benvenuto created a bronze bust of Cosimo I Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. On this statue, Cellini added three decorative heads to the duke's armor.

His most famous sculpture is the bronze group of Perseus with the Head of Medusa. This work, suggested by Duke Cosimo I de Medici, is now in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence. Cellini wanted this statue to be even better than Michelangelo's David and Donatello's Judith and Holofernes. Making this statue was very difficult for Cellini, but it was considered a masterpiece as soon as it was finished. The original smaller sculpture at the base of the statue, showing Perseus and Andromeda, is in the Bargello Museum.

Over many centuries, pollution had damaged the statue. In December 1996, it was moved to the Uffizi Gallery for cleaning and repair. It was a long process, and the restored statue was returned to its spot in June 2000.

Decorative Art and Portraits

Many of Cellini's artworks have been lost over time. Some of his decorative works that still exist include coins for the Papal and Florentine states, and a bronze bust of Bindo Altoviti. His decorative art style is very detailed and elaborate.

Besides the bronze statue of Perseus and the medals, other existing artworks include a medal of Clement VII from 1530 and a signed portrait medal of Francis I. There is also a medal of Cardinal Pietro Bembo.

One of his most famous works is the gold, enamel, and ivory salt cellar, known as Saliera. He made this for Francis I of France. This detailed sculpture is 26 cm high and is worth a lot of money. It shows a naked sea god and a woman sitting across from each other, representing the planet Earth.

The Saliera was stolen from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in 2003. The thief climbed scaffolding and broke windows to get in. Alarms went off, but they were thought to be false. The theft wasn't discovered until the next morning. On January 21, 2006, the Saliera was found by the Austrian police and returned to the museum.

One important work from later in Cellini's life was a life-size crucifix carved from marble. He originally wanted it for his own tomb, but it was sold to the Medici family, who gave it to Spain. Today, the crucifix is in the Escorial Monastery near Madrid. It is usually displayed with a loincloth and a crown of thorns added by the monastery.

While working at the papal mint in Rome, Cellini created dies for several coins and medals that still exist. He also worked for Alessandro de Medici, the first duke of Florence. Some experts believe he also made several plaques, like "Jupiter crushing the Giants." Other works, like the portrait bust shown, are thought to be from his workshop.

Lost Artworks

Many of Cellini's important works have been lost. These include an unfinished chalice for Clement VII and a gold cover for a prayer book for Pope Paul III. He also made large silver statues of Jupiter, Vulcan, and Mars for Francis I of France during his time in Paris. A bust of Julius Caesar and a silver cup for the cardinal of Ferrara are also lost.

The magnificent gold "button" or morse (a clasp for a cape) that Cellini made for the cape of Clement VII was likely melted down by Pope Pius VI. This happened in 1797 when Napoleon demanded money from the Papal States. The pope was allowed to pay part of the sum with gold and jewels. Drawings of this beautiful morse, showing its precious stones, including a very large diamond, exist in the British Museum.

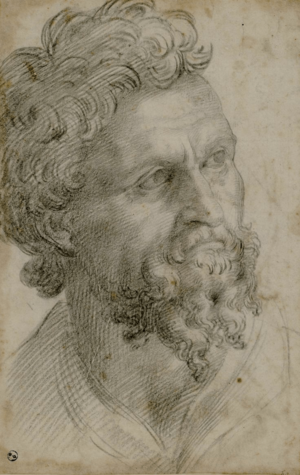

Drawings and Sketches

Benvenuto Cellini also created many drawings and sketches. Some of them include:

- Cellini, Benvenuto. Bearded Man. (1540–1543) (?) Royal Library, Turin.

- Cellini, Benvenuto. Study of a man, body and profile. (1540–1543) (?) Royal Library, Turin.

- Cellini, Benvenuto. Paint Self-Portrait. 1558–1560. Private collection.

- Benvenuto. Juno. Drawing on paper. Cabinet of Drawings, Louvre Museum, Paris.

- Cellini, Benvenuto. Satyr. National Gallery of Art, Washington.

- Cellini, Benvenuto. A Study for the Seal of the Accademia del Disegno. Louvre, Paris.

- Cellini, Benvenuto. Mourning Woman. Louvre Museum, Paris.

Cellini's Influence in Books, Music, and Movies

His Autobiography

The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini was started when he was 58 years old and finished around age 63. This book tells a detailed story of his unique life, including his feelings and adventures. It is written in a lively and direct style. One writer said it was "the most delightful autobiography ever written." Cellini's writing shows that he thought highly of himself, sometimes even exaggerating.

His book also describes some amazing events. For example, he wrote about seeing a group of spirits in the Colosseum and a special glow of light around his head after his time in prison. He also mentioned being poisoned twice.

His autobiography has been translated into English many times and is considered a classic. It is known as one of the most interesting autobiographies from the Renaissance period.

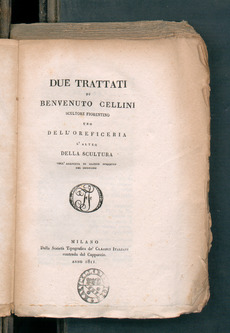

Other Writings

Cellini also wrote books about the goldsmith's art, sculpture, and design.

How Cellini Inspired Others

Many works of art, music, and literature have been inspired by Benvenuto Cellini or mention him:

- The French writer Alexandre Dumas, père was inspired by Cellini's life. His 1843 novel L'Orfèvre du roi, ou Ascanio is about Cellini's years in France and focuses on his apprentice, Ascanio. This novel was later used for a play and an opera by Camille Saint-Saëns called Ascanio.

- The watch company Rolex named their line of fancy watches "Cellini."

- Balzac mentions Cellini's Saliera in his 1831 novel La Peau de chagrin.

- Cellini was the subject of an opera by Hector Berlioz and another by Franz Lachner.

- His life is also the subject of the musical The Firebrand of Florence by Ira Gershwin and Kurt Weill.

- The Affairs of Cellini is a 1934 comedy film based on a play about Cellini.

- Mark Twain often mentioned Cellini in his books. Tom Sawyer talks about Cellini's autobiography in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Cellini's work is also mentioned in The Prince and the Pauper and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.

- Herman Melville compares his character Ahab to a Cellini sculpture in Moby-Dick.

- Judy Abbott mentions Cellini's autobiography in Jean Webster's novel Daddy-Long-Legs.

- In Victor Hugo's novel Les Misérables, Cellini is mentioned to show that talented people can be found in unexpected places.

- The Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí was also greatly influenced by Cellini's life, creating many etchings and sketches based on his stories.

- Cellini's autobiography is mentioned several times in Muriel Spark's Loitering With Intent.

- Lois McMaster Bujold based the character Prospero Beneforte in her 1992 fantasy novel The Spirit Ring loosely on Cellini.

- The American poet Frank Bidart wrote a long poem about Cellini called "The Third Hour of the Night."

- Ian Fleming mentions Cellini multiple times in his James Bond novels, comparing villains to Cellini's artistic skill.

- Fictional works by Cellini appear in Agatha Christie's The Labours of Hercules, Nathaniel Hawthorne's "Rappaccini's Daughter", and the film The Girl from Missouri (1934).

- In The Medusa Amulet by Roberto Masello, Cellini creates a powerful amulet.

- Evelyn Anthony's The Poellenberg Inheritance (1972) features a fictional salt shaker inspired by the Saliera.

- Cellini is mentioned in George Orwell's Down and Out in Paris and London.

- The fictional secret agent, Nick Carter, owns a special knife said to have been made by Cellini.

- The 1966 film How to Steal a Million is about trying to steal a fake Venus statue supposedly made by Cellini.

- The 1923 play A Man of His Time by Helen de Guerry Simpson is entirely about Benvenuto Cellini.

|

See also

In Spanish: Benvenuto Cellini para niños

In Spanish: Benvenuto Cellini para niños