Pope Clement VII facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pope Clement VII |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

|

|

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Papacy began | 19 November 1523 |

| Papacy ended | 25 September 1534 |

| Predecessor | Adrian VI |

| Successor | Paul III |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 19 December 1517 |

| Consecration | 21 December 1517 by Leo X |

| Created Cardinal | 23 September 1513 |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici |

| Born | 26 May 1478 Florence, Republic of Florence |

| Died | 25 September 1534 (aged 56) Rome, Papal States |

| Buried | Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome |

| Parents | Giuliano de' Medici Fioretta Gorini |

| Previous post |

|

| Motto | Candor illæsus (Innocence inviolate) |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Other Popes named Clement | |

Pope Clement VII (born Giulio de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was the leader of the Catholic Church. He also ruled the Papal States from 1523 until his death in 1534. He is known as one of the most unlucky popes. His time as Pope was filled with many political, military, and religious problems. These problems had a huge impact on Christianity and world politics.

Clement became Pope in 1523, near the end of the Italian Renaissance. He was well-respected for his skills as a statesman. He had been a top advisor to Pope Leo X and Pope Adrian VI. He also did a great job leading Florence. When he became Pope, the Church faced many challenges. The Protestant Reformation was spreading. The Church was almost out of money. Large foreign armies were invading Italy.

At first, Clement tried to bring Christian leaders together to make peace. Later, he tried to free Italy from foreign control. He believed this control threatened the Church's freedom. However, the political situation in the 1520s made his efforts very difficult.

He faced many big problems. Martin Luther's Protestant Reformation was growing in Northern Europe. Two powerful kings, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Francis I of France, were fighting over Italy. Both kings wanted the Pope to pick their side. Also, Turkish armies led by Suleiman the Magnificent were invading Eastern Europe.

Clement's problems got even worse. King Henry VIII of England wanted a divorce, which led to England breaking away from the Catholic Church. In 1527, his relationship with Emperor Charles V turned bad. This led to the violent Sack of Rome, where Clement was captured. After escaping from the Castel Sant'Angelo, Clement had few choices left. He made a deal with Charles V, which affected the Church's and Italy's independence.

Clement was a good and religious person. He was very smart and had a strong character. Some historians believe that in calmer times, he would have been a very successful Pope. But he did not fully understand how much the Pope's power had changed. Europe's new nations and Protestantism were changing everything.

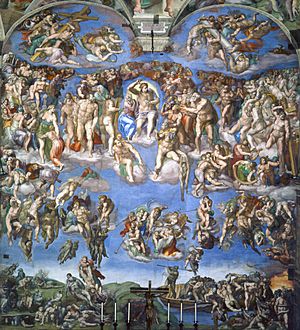

Clement left behind an important cultural legacy, like other Medici family members. He asked famous artists like Raphael, Benvenuto Cellini, and Michelangelo to create artworks. This included Michelangelo's The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. In science, Clement is known for approving Nicolaus Copernicus's idea in 1533. Copernicus believed the Earth revolved around the Sun. This was 99 years before Galileo Galilei faced trial for similar ideas.

Early Life and Family

Giulio de' Medici's life started sadly. On April 26, 1478, his father, Giuliano de Medici, was killed. This happened in the Florence Cathedral by enemies of his family. This event is known as "The Pazzi Conspiracy." Giulio was born a month later, on May 26, 1478, in Florence. We do not know for sure who his mother was. Many experts believe it was Fioretta Gorini. Giulio lived with his godfather, the architect Antonio da Sangallo the Elder, for his first seven years.

After that, Lorenzo the Magnificent raised Giulio as his own son. He grew up with Lorenzo's children, including Giovanni (who became Pope Leo X). Giulio was educated at the Palazzo Medici in Florence. He studied with smart people like Angelo Poliziano and artists like Michelangelo. Giulio became a skilled musician. People said he was shy but handsome.

Giulio wanted to join the clergy, but being born outside of marriage made it hard to get high Church positions. So, Lorenzo the Magnificent helped him become a soldier. He joined the Knights Hospitaller. He also became the Grand Prior of Capua. In 1492, Lorenzo the Magnificent died. Giovanni de' Medici became a cardinal, and Giulio got more involved in Church matters. He studied Church law at the University of Pisa. He went with Giovanni to the 1492 meeting where Rodrigo Borgia was chosen as Pope Alexander VI.

The Medici family was forced out of Florence in 1494. This happened after problems with Lorenzo the Magnificent's oldest son, Piero the Unfortunate. Cardinal Giovanni and Giulio traveled around Europe for six years. They were arrested twice. Each time, Piero the Unfortunate helped them get out. In 1500, they returned to Italy. They worked to get their family back in charge of Florence. Both were at the Battle of Ravenna in 1512. Cardinal Giovanni was captured by the French, but Giulio escaped. Giulio then became a messenger for Pope Julius II. That same year, the Medici family took control of Florence again. This was with help from Pope Julius and Spanish troops.

Alessandro de' Medici's Paternity

In 1510, a servant in the Medici household became pregnant. She gave birth to a son named Alessandro de' Medici. He was called "il Moro" ("the Moor") because of his dark skin. Alessandro was officially recognized as the son of Lorenzo II de Medici. However, many scholars believe he was the son of Giulio de' Medici. The truth about his father is still debated.

No matter who his father was, Giulio showed Alessandro great favor. As Pope Clement VII, he made Alessandro Florence's first hereditary ruler. This was even though Ippolito de Medici was also qualified.

Becoming a Cardinal

Working for Pope Leo X

Giulio de' Medici became well-known in March 1513. He was 35 years old when his cousin Giovanni de' Medici was elected Pope. Giovanni took the name Leo X. Pope Leo X ruled until his death in December 1521.

Giulio de' Medici was seen as "learned, clever, respectable, and hardworking." His reputation and duties grew very quickly. This was unusual even for the Renaissance period. Within three months of Leo X's election, Giulio was named Archbishop of Florence. Later that year, a special Church order removed all obstacles to him becoming a high-ranking Church official. This order said his parents had been engaged. This allowed Leo X to make him a cardinal on September 23, 1513. He was then given an important position as Cardinal Deacon.

People at the time noted Cardinal Giulio's influence. Marco Minio, a Venetian ambassador, wrote in 1519 that Cardinal de' Medici had great power with the Pope. He was a very capable and important man. He lived with the Pope and nothing important was done without his advice.

Statesmanship

Cardinal Giulio was not officially second-in-command of the Church until 1517. But Pope Leo X worked closely with his cousin from the start. Giulio's main jobs were managing Church matters in Florence and handling international relations. In 1514, King Henry VIII of England made him a protector of England. The next year, King Francis I of France nominated him for a high Church position in France. In 1516, Francis I also named him a protector of France.

This showed Giulio's independent thinking. The kings of England and France saw a conflict of interest. They wanted Giulio to give up one of his protector roles. But he refused to do so.

Cardinal Giulio's foreign policy aimed to free Italy and the Church. He wanted to protect them from French and Imperial control. This became clear in 1521. King Francis I and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V started a war in northern Italy. Francis I expected Giulio to support him. But Giulio believed Francis was threatening the Church's independence. Especially Francis's control of Lombardy.

At that time, the Church wanted Emperor Charles V to fight against Lutheranism in Germany. So, Cardinal Giulio arranged an alliance for the Church. They supported the Holy Roman Empire against France. That autumn, Giulio helped lead a winning army against the French in Milan. His strategy of changing alliances to free the Church and Italy was difficult. But during Leo X's rule, it helped keep a balance of power.

Achievements

Cardinal Giulio also had other successes for Pope Leo X. He was seen as the main person guiding papal policy. In 1513, he helped heal a split in the Church. In 1515, he set rules for religious preaching. He also led the Florentine Synod in 1517. There, he put into practice reforms from an important Church council. These reforms included telling priests not to carry weapons or go to taverns. He also urged them to go to confession weekly.

Cardinal Giulio also supported many artists. He asked Raphael to paint The Transfiguration. He also asked Michelangelo to create sculptures for the Medici Chapel. Goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini praised his "excellent taste" in art.

Leading Florence

Cardinal Giulio governed Florence from 1519 to 1523. This was after the death of its ruler, Lorenzo II de Medici. He had almost complete control of the city's affairs. He worked hard to make public services strong and practical. U.S. President John Adams later said Giulio's leadership in Florence was "very successful and careful with money." Adams wrote that Giulio improved how magistrates worked and how public money was spent. This made the citizens very happy.

When Pope Leo X died in 1521, the people of Florence wanted Cardinal de’ Medici to stay in charge. This was because of his good government.

Working for Pope Adrian VI

When Pope Leo X died in December 1521, many expected Cardinal Giulio to become the next Pope. But in 1522, the cardinals chose Adrian VI from the Netherlands instead. People knew Cardinal Giulio was Leo X's most skilled advisor. They also knew he managed the Pope's money. Many believed Leo X's problems came from ignoring Giulio's advice. Cardinal Giulio was seen as handsome, thoughtful, and artistic. Despite this, some cardinals did not want him to be Pope.

Cardinal Giulio had the most votes, but his enemies stopped him. These included Cardinal Francesco Soderini, whose family had lost power to the Medici. Also, Cardinal Pompeo Colonna wanted to be Pope himself. French cardinals were still upset about Leo X's actions against their King.

Cardinal Giulio then made a smart move. He humbly said he was not worthy of such a high office. Instead, he suggested a less-known scholar, Cardinal Adrian Dedel. Adrian was a very religious man who had taught Emperor Charles V. Cardinal Giulio thought Adrian would be rejected because he was not Italian and lacked political experience. He believed his selfless suggestion would show he was the best choice. But his plan backfired. Cardinal Adrian Dedel was elected as Pope Adrian VI.

During his 20 months as Pope, Adrian VI valued Cardinal Medici's opinions greatly. Cardinal Giulio had a lot of influence during Adrian's rule. He spent his time between Florence and Rome. He lived like a generous Medici, supporting artists and musicians. He also helped the poor and hosted many events.

Becoming Pope

After Adrian VI died in September 1523, Cardinal Giulio finally became Pope. He overcame the French king's opposition and was elected Pope Clement VII in November 1523.

Pope Clement VII was known for his political skills and diplomacy. However, some people thought he cared too much about worldly things. They also thought he did not take the dangers of the Protestant Reformation seriously enough.

When he became Pope, Clement VII sent a messenger to the Kings of France, Spain, and England. He wanted to end the Italian War. An early report said that Clement believed his first duty was to bring peace among all Christian leaders. He asked the Emperor to help him in this effort. But the Pope's attempt failed.

Politics in Europe

In 1524, Francis I of France conquered Milan. This made the Pope leave the side of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. In January 1525, he allied with other Italian leaders and France. This agreement gave the Papal States control of Parma and Piacenza. It also kept the Medici family in power in Florence. And it allowed French troops to pass through to Naples. This plan was good for Italy. But Clement VII's enthusiasm soon faded. His lack of planning and saving money left him open to attack. Roman nobles attacked him, forcing him to ask Emperor Charles V for help.

A month later, Francis I was defeated and captured at the Battle of Pavia. Clement VII then made a stronger alliance with Charles V. But Clement was worried about the Emperor's growing power. So, he allied with France again after Francis I was freed. Clement joined the League of Cognac with France, Venice, and Milan. Clement VII spoke out against Charles V. In response, Charles V called him a "wolf" instead of a "shepherd." Charles V also threatened to call a Church council about the Lutheran issue.

Like his cousin Pope Leo X, Clement was seen as too generous to his Medici relatives. He spent a lot of the Vatican's money on them. He gave them important positions, lands, titles, and money. After Clement's death, new rules were made to stop such excessive favoritism.

The Sack of Rome

The Pope's changing alliances also caused problems within the Church. Cardinal Pompeo Colonna's soldiers attacked Vatican Hill. They took control of Rome in his name. The Pope, feeling shamed, promised to bring the Papal States back to the Emperor's side. But Colonna soon left the siege and went to Naples. He did not keep his promises. From then on, Clement VII had to follow the French side.

Soon, he found himself alone in Italy. The Duke of Ferrara, Alfonso d'Este, gave artillery to the Imperial army. This kept the League Army away from the Imperial troops. The Imperial troops, led by Charles III, Duke of Bourbon and Georg von Frundsberg, reached Rome without trouble.

Charles of Bourbon died during the short siege of Rome. His hungry troops, unpaid and without a leader, began to destroy Rome on May 6, 1527. Clement VII had not shown much strength in his military or political actions. He was forced to surrender on June 6. He was inside the Castel Sant'Angelo, where he had sought safety. He agreed to pay a large ransom for his life. This included giving up some cities to the Holy Roman Empire. At the same time, Venice took advantage of his situation and captured two cities.

Clement was held prisoner in Castel Sant'Angelo for six months. He bribed some Imperial officers and escaped disguised as a peddler. He found refuge in other towns before returning to Rome in October 1528. Rome was empty and ruined.

Meanwhile, in Florence, enemies of the Medici family used the chaos to force the Pope's family out of the city again.

In June 1529, the fighting groups signed a peace treaty. The Papal States got some cities back. Charles V agreed to put the Medici family back in power in Florence. In 1530, after a long siege, Florence gave up. Clement VII made his relative Alessandro the duke. After this, the Pope mostly followed the Emperor's wishes. He tried to make the Emperor act strictly against the Lutherans in Germany. But he also tried to avoid the Emperor's demands for a general Church council.

Appearance

During his six months in prison in 1527, Clement VII grew a full beard. This was a sign of sadness for the sack of Rome. This went against Catholic Church law, which said priests should be clean-shaven. However, Pope Julius II had also worn a beard for nine months in 1511–12. He did this to show sadness for the city of Bologna.

Unlike Julius II, Clement kept his beard until he died in 1534. His example of wearing a beard was followed by 24 popes after him. This fashion lasted for over a century.

English Reformation

By the late 1520s, King Henry VIII wanted his marriage to Catherine of Aragon to be declared invalid. Their sons had died as babies, which put the future of the royal family at risk. Henry did have a daughter, Mary Tudor. Henry claimed that not having a male heir was because his marriage was "cursed by God." Catherine had been his brother's widow. But their marriage had no children, so marrying her was not against Old Testament law. Also, Pope Julius II had given special permission for the wedding. Henry now argued that this permission was wrong and his marriage was never valid.

In 1527, Henry asked Clement to declare the marriage invalid. But the Pope refused. He was likely under pressure from Catherine's nephew, Emperor Charles V, who held him captive. Catholic teaching says a valid marriage cannot be broken until death. So, the Pope cannot declare a marriage invalid if permission was given before. Many people close to Henry wanted to ignore Clement. But in 1530, a meeting of clergy and lawyers said that the English Parliament could not allow the Archbishop of Canterbury to go against the Pope. In Parliament, Bishop John Fisher supported the Pope.

Henry then married Anne Boleyn in late 1532 or early 1533. This marriage was made easier when the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham, died. Warham was a strong supporter of the Pope. Henry then convinced Clement to appoint Thomas Cranmer as the new Archbishop. Cranmer was a friend of the Boleyn family. The Pope gave the necessary orders for Cranmer to become Archbishop. He also asked Cranmer to take the usual oath of loyalty to the Pope. However, laws made under Henry already said bishops could be appointed without papal approval. Cranmer was appointed, but he said beforehand that he did not agree with the oath he would take. Cranmer was ready to declare Henry's marriage to Catherine invalid, as Henry wanted. The Pope responded by removing both Henry and Cranmer from the Catholic Church.

As a result, in England, taxes on Church income were transferred from the Pope to the King. An act also made it illegal to pay an annual fee to the Pope. This act also stated that England had "no superior under God, but only your Grace." It said Henry's "imperial crown" had been lessened by the Pope's "unreasonable demands." Finally, in 1534, Henry led the English Parliament to pass the Act of Supremacy. This act created the independent Church of England and broke away from the Catholic Church.

Catherine de' Medici's Marriage

In 1533, Clement arranged the marriage of his cousin's granddaughter, Catherine de Medici. She married the future King Henry II of France, son of King Francis I. Before traveling for the wedding, Clement issued an order in case he died outside Rome. The wedding took place in Marseilles on October 28, 1533. Clement himself performed the ceremony. It was followed by nine days of grand parties and celebrations. In Marseilles, Clement also appointed four new cardinals, all French. He also had private meetings with Francis I and Charles V. Charles's daughter, Margaret of Austria, was set to marry Clement's relative, Duke Alessandro de’ Medici, in 1536.

According to historian Paul Strathern, these marriages were a major turning point for the Medici family. Catherine married into France's royal family. Alessandro became Duke of Florence and married into the Hapsburg family. Strathern says that without Clement VII's guidance, the Medici family would not have reached such high levels of greatness in the centuries that followed.

Death

Clement returned to Rome on December 10, 1533. He had a fever and stomach problems. He had been sick for months and was "aging rapidly." Strathern writes that "his liver was failing and his skin turned yellow." He also lost sight in one eye and became partly blind in the other. By early August 1534, he was so ill that his doctors feared for his life. On September 23, 1534, Clement wrote a long farewell letter to Emperor Charles. Just days before his death, he also confirmed that Michelangelo should paint The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. Clement VII died on September 25, 1534. He was 56 years old. He had been Pope for 10 years, 10 months, and 7 days. His body was buried in Saint Peter's Basilica. Later, it was moved to a tomb in Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome. This tomb was designed by Baccio Bandinelli.

Some people at the time thought he was poisoned, possibly by a type of mushroom. However, Clement's symptoms and the long time he was ill do not support this idea.

Legacy

Political Impact

Clement VII's time as Pope is often seen as one of the most difficult in history. Opinions of Clement himself are often mixed. For example, a writer from his time, Francesco Vettori, said Clement worked hard to become Pope. But he became a "small and little-esteemed pope" from a "great and respected cardinal." However, Vettori also said that Clement was a better man than many popes before him. Yet, the disasters happened during his time, while other popes, who had many faults, lived happily.

The disasters during Clement's time as Pope, like the Sack of Rome and the English Reformation, were major turning points. They changed the history of Catholicism, Europe, and the Renaissance. Modern historian Kenneth Gouwens says Clement's failures happened because European politics were changing greatly. Wars in Italy needed huge amounts of money for armies. Surviving politically became more important than Church reform. The costs of war meant less money for art and culture. Clement followed the policies of earlier popes. But in the 1520s, these policies could not succeed. Reforming the Church, which later popes did, needed money and strong support from rulers. Clement, the second Medici pope, could not gather these.

Regarding Clement's fight to free Italy and the Catholic Church from foreign control, historian Fred Dotolo says Clement tried to protect the Pope's rights. He fought against the growing power of kings. He tried to keep the old division between religious and royal power in Christianity. If new kings made the Pope just a part of their government, religious issues would become just state policy. Clement VII tried to stop the growth of royal power. He wanted to keep Rome and the Pope's special powers independent.

In Church matters, Clement is remembered for protecting Jews from the Inquisition. He approved new religious orders like the Theatine, Barnabite, and Capuchin Orders. He also secured the island of Malta for the Knights of Malta.

Support for Arts and Science

As both a cardinal and Pope, Giulio de’ Medici asked for or oversaw many famous art projects of the 1500s. Among these, he is best known for Michelangelo's huge painting in the Sistine Chapel, The Last Judgment. He also supported Raphael’s famous painting The Transfiguration. He asked Michelangelo to create sculptures for the Medici Chapel in Florence. He also supported Raphael's building design for Villa Madama in Rome. And he supported Michelangelo's unique Laurentian Library in Florence.

As a patron, Giulio de’ Medici was very confident in technical matters. He could suggest good ideas for building and art projects. These included Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library and Benvenuto Cellini’s famous Papal Morse. As Pope, he made goldsmith Cellini the head of the Papal Mint. He also made painter Sebastiano del Piombo the keeper of the Papal Seal. Sebastiano's great painting, The Raising of Lazarus, was created through a competition. Cardinal Giulio arranged it to see who, Sebastiano or Raphael, could paint a better altarpiece.

Giulio de’ Medici also supported theology, literature, and science. Some well-known works connected to him include Erasmus’ On the Bondage of the Will. He encouraged this in response to Martin Luther’s criticisms of the Catholic Church. He also asked for Machiavelli’s Florentine Histories. And he personally approved Copernicus’ heliocentric idea in 1533. When Johann Widmanstetter explained the Copernican system to him, he was so thankful that he gave Widmanstetter a valuable gift. In 1531, Clement set rules for overseeing human body dissection and medical tests. This was an early form of medical ethics. The humanist and author Paolo Giovio was his personal doctor.

Giulio de’ Medici was a talented musician. Many famous artists and thinkers of the Italian High Renaissance were part of his circle. For example, before he became Pope, the future Clement VII was close to Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo even gave him a painting, the Madonna of the Carnation. He supported the writer Pietro Aretino. Aretino wrote funny and sharp writings supporting Giulio de’ Medici to become Pope. As Pope, he appointed author Baldassare Castiglione as a diplomat to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. He also made historian Francesco Guicciardini the governor of the Romagna, a northern part of the Papal States.

The Clementine Style

Italian Renaissance art from 1523 to 1527 is sometimes called the "Clementine style." It is known for its amazing technical skill. In 1527, the Sack of Rome brutally ended this artistic golden age. André Chastel describes artists who worked in the Clementine style. These included Parmigianino, Rosso Fiorentino, Sebastiano del Piombo, Benvenuto Cellini, Marcantonio Raimondi, and many artists who worked with Raphael. During the Sack of Rome, some of these artists were killed, captured, or fought in the battles.

Character

Clement was known for his intelligence and good advice. But he was criticized for not being able to make quick and firm decisions. Historian G.F. Young writes that Clement spoke with great knowledge about many topics. These included philosophy, theology, mechanics, and building with water. He showed amazing sharpness in all matters. He could solve the most confusing problems and understand the hardest situations. No one could debate a point with more skill.

Historian Paul Strathern writes that Clement had a strong inner faith. He was also surprisingly connected to the ideas of Renaissance humanism. He was very open to them. For example, Clement VII had no trouble accepting Copernicus’s heliocentric idea. He did not see it as a challenge to his faith. He had inherited his father’s good looks. But his face often looked like a dark frown instead of a smile. He also inherited some of his great-grandfather Cosimo de’ Medici’s skill with money. He also had a strong tendency to be very careful. This made the new Pope hesitant when making important decisions. Unlike his cousin Leo X, he had a deep understanding of art.

About Clement's weaknesses, historian Francesco Guicciardini writes that Clement had a very capable mind. He had amazing knowledge of world affairs. But he lacked the courage and action to match it. He almost always stayed undecided when he had to make choices. These were things he had often seen, thought about, and almost figured out from a distance. Strathern writes that Clement was a man of almost perfect self-control. But in him, the Medici trait of being careful had become a flaw. Clement VII understood too much. He could always see both sides of any argument. This made him an excellent close advisor to his cousin Leo X. But it stopped him from taking matters into his own hands. The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that his private life was without fault. He had many good intentions. But despite good intentions, he lacked heroism and greatness.

See also

In Spanish: Clemente VII (papa) para niños

In Spanish: Clemente VII (papa) para niños

- Republic of Florence

- Italian Wars

- Medici family

- List of popes from the Medici family

- Cardinals created by Clement VII

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Cosimo de' Pazzi |

Archbishop of Florence 1513–1523 |

Succeeded by Cardinal Nicolò Ridolfi |

| Preceded by Cardinal Guillaume Briçonnet |

Archbishop of Narbonne 1515–1523 |

Succeeded by Cardinal Jean de Lorraine |

| Preceded by Giovanni Battista Orsini |

Apostolic Administrator of Bitonto 8 February – November 1517 |

Succeeded by Giacomo Orsini |

| Preceded by Cardinal Achille Grassi |

Bishop of Bologna 8 January – 3 March 1518 |

Succeeded by Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggi |

| Preceded by Cardinal Niccolò Fieschi |

Apostolic Administrator of Embrun 5–30 July 1518 |

Succeeded by François de Tournon |

| Preceded by Girolamo Ghinucci |

Apostolic Administrator of Ascoli Piceno 30 July – 3 September 1518 |

Succeeded by Filos Roverella |

| Preceded by Cardinal Ippolito d'Este |

Bishop of Eger 1520–1523 |

Succeeded by Pál Várdai |

| Preceded by Silvestro de' Gigli |

Apostolic Administrator of Worcester 1521–1522 |

Succeeded by Cardinal Girolamo Ghinucci |

| Preceded by Adrian VI |

Pope 19 November 1523 – 25 September 1534 |

Succeeded by Paul III |