Niccolò Machiavelli facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Niccolò Machiavelli

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Machiavelli by Santi di Tito

|

|

| Born | 3 May 1469 Florence, Republic of Florence

|

| Died | 21 June 1527 (aged 58) Florence, Republic of Florence

|

|

Notable work

|

The Prince Discourses on Livy |

| Spouse(s) |

Marietta Corsini

(m. 1502) |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Classical realism Republicanism |

|

Main interests

|

Politics and political philosophy, military theory, history |

|

Notable ideas

|

Classical realism, virtù, multitude, national interest |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

Niccolò Machiavelli (born May 3, 1469 – died June 21, 1527) was an Italian diplomat, writer, thinker, and historian. He lived during the Renaissance, a time of great change in Europe.

Machiavelli is most famous for his book The Prince (Il Principe). He wrote it around 1513, but it was published after his death in 1532. Many people call him the founder of modern political philosophy and political science.

For many years, he worked as an important official in the Florentine Republic. His jobs included dealing with other countries and military matters. He also wrote plays, songs, and poems. His personal letters are important for historians who study Italy. He was a secretary for Florence's government from 1498 to 1512. This was when the powerful Medici family was not in charge.

After he died, Machiavelli's name became linked to tricky and dishonest actions. This is because of the advice he gave in The Prince. He believed that politics had always involved cheating, betrayal, and even crime. He also said that a ruler who creates a new kingdom or republic should be excused for harsh actions, like violence. This is true if the actions help the ruler and the people in the end.

The Prince has been debated ever since it came out. Some people think it simply describes how politics really works. Others see it as a guide for rulers on how to gain and keep power. The word Machiavellian often means being politically sneaky or dishonest.

Even though The Prince is his most famous work, scholars also study his other writings. His book Discourses on Livy, written around 1517, helped shape modern republicanism. His ideas greatly influenced thinkers during the Age of Enlightenment. These thinkers were interested in classical republicanism, like Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Machiavelli's realistic view of politics still influences many people today.

Contents

Niccolò Machiavelli: A Renaissance Thinker

Early Life and Times

Machiavelli was born in Florence, Italy. He was the third child and first son of Bernardo di Niccolò Machiavelli, a lawyer. His mother was Bartolomea di Stefano Nelli. The Machiavelli family was old and important in Florence.

Machiavelli grew up in a time of great change and trouble. Italian city-states, and the families who ruled them, could rise and fall very quickly. Popes and kings from France, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire fought wars for control. Alliances between leaders changed constantly. Mercenary leaders, called condottieri, often switched sides without warning. Many governments were short-lived.

Machiavelli learned grammar, public speaking, and Latin from his teacher. It is not known if he knew Greek, even though Florence was a center for Greek studies. In 1494, Florence became a republic again. The Medici family, who had ruled for about 60 years, were forced out.

Machiavelli's Career in Florence

Soon after a religious leader named Girolamo Savonarola was executed, Machiavelli got a job in the government. He was in charge of writing official government documents. He also became the secretary of a group called the Dieci di Libertà e Pace.

In the early 1500s, he went on several important diplomatic trips. One of the most notable was to the Pope in Rome. Florence sent him to Pistoia to calm down two fighting groups. When this failed, the leaders were sent away from the city. Machiavelli had supported this idea from the start.

From 1502 to 1503, he saw how Cesare Borgia and his father, Pope Alexander VI, built their power. They tried to take control of a large part of Central Italy. They used the excuse of protecting Church interests. His trips to the courts of Louis XII in France and the Spanish court also influenced his writings.

In the early 16th century, Machiavelli had an idea for Florence to have its own army. He started recruiting and creating this army. He did not trust mercenaries, who were soldiers for hire. He believed they were not loyal and could not be relied on. Instead, he wanted citizens to be soldiers. This idea was very successful. By 1506, he had 400 farmers marching in parade. They wore iron armor and carried lances and small firearms. Under his command, Florentine citizen-soldiers defeated Pisa in 1509.

What Happened After the Medici Returned?

Machiavelli's success did not last. In 1512, the Medici family, supported by Pope Julius II, used Spanish troops to defeat Florence. After this defeat, the head of Florence's government resigned and went into exile. This experience, like his time in foreign courts, greatly influenced his political writings.

The Florentine republic was ended, and Machiavelli lost his job. He was also banned from the city for a year. In 1513, the Medici family accused him of plotting against them. He was put in prison and questioned. Even though he was treated harshly, he said he was not involved. He was released after three weeks.

Machiavelli then went to live on his farm near San Casciano in Val di Pesa. There, he spent his time studying and writing his political books. He visited places in France, Germany, and Italy where he had worked for Florence. He felt sad that he could no longer be directly involved in politics. After some time, he started joining intellectual groups in Florence. He wrote several plays that were popular during his lifetime. Politics remained his main interest. He kept writing letters to friends who were still involved in politics, hoping to return to public life.

Machiavelli died on June 21, 1527, at age 58. He was buried at the Church of Santa Croce in Florence. Later, a monument was built on his tomb.

His Most Famous Books

The Prince: A Guide for Rulers

Machiavelli's most famous book, Il Principe (The Prince), gives advice on how to rule. It focuses on a "new prince" who has just gained power. A ruler who inherits power must balance many interests. But a new prince has a harder job. He must first make his power strong to build a lasting government.

Machiavelli suggested that a ruler might need to act without morals to keep stability and safety. He believed that public and private morals were different. A ruler should care about his reputation. But he also must be ready to act without morals when needed. Machiavelli thought it was better for a ruler to be feared than loved. A loved ruler keeps power because people feel they owe him. A feared ruler keeps power because people are afraid of punishment.

Machiavelli stressed that a ruler might need to use force or trickery. This could include getting rid of powerful families. This prevents anyone from challenging the ruler's power. Scholars often say that Machiavelli believed "the ends justify the means". This means that a good outcome makes harsh actions acceptable.

Because of its controversial ideas, the Catholic Church banned The Prince. They put it on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a list of forbidden books. Some thinkers of the time also disliked the book. The Prince was important because it separated political realism from political idealism. It was a guide on how to get and keep political power.

Some people argue that The Prince actually supports republics. This is similar to ideas in his other book, Discourses on Livy. In the 18th century, some, like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, even called it a satire. They thought it was a hidden warning about bad rulers.

Discourses on Livy: Ideas for Republics

Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livius, often called Discourses, was written around 1517. It was published in 1531. This book discusses the history of early Ancient Rome. But it also uses examples from Machiavelli's own time.

Machiavelli presents it as lessons on how to start and run a republic. It is much longer than The Prince. It openly explains the benefits of republics. But it also has many similar ideas to his other works. For example, Machiavelli said that to save a republic from corruption, it might need a "kingly state" using harsh methods. He even excused Romulus for killing his brother Remus to gain total power. This was because Romulus established a "civil way of life."

People disagree on how much The Prince and Discourses agree. Machiavelli often calls leaders of republics "princes." He sometimes even acts as an advisor to tyrants. Other scholars point out that Machiavelli's republic was ambitious and aimed for expansion. Still, Discourses became a key book for modern republicanism. Many believe it is a more complete work than The Prince.

Why Are His Ideas Still Important?

Realism in Politics

Machiavelli is sometimes seen as an early scientist. He built his ideas from experience and history. He believed that simply imagining ideal societies was not useful for understanding politics.

Machiavelli felt that his traditional education did not help him understand politics. But he strongly believed in studying the past. He thought understanding how a city was founded was key to its future. He also studied how people lived. He wanted to tell leaders how they should rule and even how they should live.

Machiavelli did not agree that living a good life always leads to happiness. For example, he saw misery as something that could help a prince rule. He famously said, "it would be best to be both loved and feared. But since the two rarely come together, anyone compelled to choose will find greater security in being feared than in being loved." He often stated that a ruler must use harsh policies to keep his government going.

The Role of Luck and Effort

Machiavelli was critical of Christianity as it was practiced in his time. He thought it made people too passive. He believed it encouraged people to leave events up to fate or chance. Christianity sees modesty as a good thing and pride as a sin. But Machiavelli thought ambition and seeking glory were good and natural. He saw them as part of the virtue and prudence a good prince should have.

He argued that virtue and prudence could help a person control their future. This was instead of letting luck decide everything. Machiavelli's ideas were not entirely new. But he went further than others. He promoted the idea of creating a new state, even if it meant going against old traditions.

Religion and Society

Machiavelli often showed that he saw religion as something created by humans. He believed religion's value was in helping keep social order. He thought moral rules could be ignored if security required it. In The Prince and Discourses, he described "prophets" like Moses and Romulus. He treated pagan and Christian leaders the same way. He saw them as great new princes who used force and violence to create new political systems.

He believed these systems lasted for a very long time. Machiavelli worried that Christianity made people weak and inactive. He thought it left politics to cruel leaders without a fight. He felt that having a religion was essential for a republic to stay in order. For Machiavelli, a truly great prince might not be religious himself. But he should make his people religious if he could.

Different Ideas in Government

Machiavelli's ideas were very realistic. He was willing to argue that good goals could justify bad actions. This led to important new ideas in modern politics.

In Discourses on Livy, Machiavelli sometimes saw a positive side to disagreements within republics. For example, he wrote that the disagreements between the common people and the senate in Rome "kept Rome free." The idea that a community has different groups with different interests is old. But Machiavelli's strong way of presenting it was new. It was a key step towards later ideas like the division of powers or checks and balances. These ideas were important for the US Constitution.

Similarly, modern economic ideas, like capitalism, often talk about "public virtue from private vices." This means good things for society can come from individual selfish actions. Machiavelli's focus on being realistic and ambitious, even risking encouraging bad behavior, was a key step toward this idea.

How Machiavelli Influenced Others

Machiavelli's ideas had a big impact on political leaders. This was helped by the new invention of the printing press. At first, his influence was mostly on non-republican governments. For example, The Prince was admired by Thomas Cromwell in England. It influenced King Henry VIII in his move towards Protestantism. Even the Catholic king Charles V had a copy. In France, Machiavelli became linked to Catherine de' Medici and a terrible event called the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.

In the 16th century, Catholic writers linked Machiavelli to Protestants. Protestant writers saw him as Italian and Catholic. In reality, he influenced both Catholic and Protestant rulers.

One important early book that criticized Machiavelli was by Innocent Gentillet. He accused Machiavelli of being an atheist. He said that Machiavelli's writings were like the "Koran of the courtiers." This meant that politicians knew his ideas very well. Gentillet also questioned if immoral strategies actually worked. This became a big topic in European politics during the 17th century. Many writers criticized Machiavelli but also followed some of his ideas. They agreed that a ruler needed a good reputation. They also accepted that cunning and trickery might be needed. But they focused more on economic progress than on war.

Modern materialist philosophy developed after Machiavelli. This philosophy often supported republics. Machiavelli's realism and his encouragement to use new ideas to control one's future were accepted. But his focus on war and violence was less popular. This led to new ideas in economics and politics. It also led to modern science. Some people say the 18th-century Enlightenment softened Machiavelli's ideas.

Machiavelli's influence is seen in many important thinkers. These include Francis Bacon, Harrington, John Milton, Spinoza, Rousseau, and Adam Smith. Even if they didn't always name him, he influenced others like Hobbes and Locke.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was influenced by Machiavelli, even though his political ideas were different. Rousseau thought Machiavelli's work was a satire. He believed Machiavelli was showing the problems of one-person rule, not praising bad behavior.

Scholars believe Machiavelli greatly influenced the Founding Fathers of the United States. This is because he strongly favored republicanism. It is still debated whether Machiavelli was "an advisor of tyranny or partisan of liberty." Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson followed Machiavelli's republican ideas. They opposed what they saw as a growing aristocracy.

John Adams was perhaps the Founding Father who studied Machiavelli the most. He praised Machiavelli as a defender of mixed government. Adams agreed that Machiavelli brought practical thinking back to politics. He also liked Machiavelli's ideas about different groups in society. Adams believed human nature was unchanging and driven by feelings. He also accepted Machiavelli's idea that societies go through cycles of growth and decline. Adams thought Machiavelli only lacked a clear understanding of good government institutions.

20th century

In the 20th century, the Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci was inspired by Machiavelli's writings. He studied Machiavelli's ideas on ethics, morals, and their connection to the State.

Joseph Stalin read The Prince and wrote notes in his own copy.

There was also new interest in Machiavelli's play La Mandragola (1518). It was performed many times, including in New York and London.

The Meaning of "Machiavellian"

Machiavelli is most famous for The Prince. It was written in 1513 but published in 1532, after his death. Since the 16th century, leaders have been both drawn to and repelled by its ideas. It accepts, and even encourages, the lack of morals in powerful people. This is described in The Prince and his other works.

His writings are sometimes said to have made the words politics and politician have negative meanings today. It is also thought that because of him, "Old Nick" became an English name for the Devil. More clearly, the word Machiavellian means a type of politics that is "marked by cunning, trickery, or dishonesty." Machiavellianism is still a common term in political talks. It often means a very tough and realistic approach to politics.

While Machiavellianism is clear in his works, scholars agree that his writings are complex. They have other important ideas too. For example, J.G.A. Pocock saw him as a key source of republicanism. This idea spread through England and North America in the 17th and 18th centuries. Whatever his true intentions, which are still debated, he is linked to the idea that "the end justifies the means."

Other Writings by Machiavelli

Political and historical works

- Discorso sopra le cose di Pisa (1499) – A speech about the affairs of Pisa.

- Del modo di trattare i popoli della Valdichiana ribellati (1502) – How to deal with the rebellious people of Valdichiana.

- Descrizione del modo tenuto dal Duca Valentino nello ammazzare Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliverotto da Fermo, il Signor Pagolo e il duca di Gravina Orsini (1502) – A description of how Duke Valentino killed certain leaders.

- Discorso sopra la provisione del danaro (1502) – A talk about providing money.

- Ritratti delle cose di Francia (1510) – A look at the affairs of France.

- Ritracto delle cose della Magna (1508–1512) – A look at the affairs of Germany.

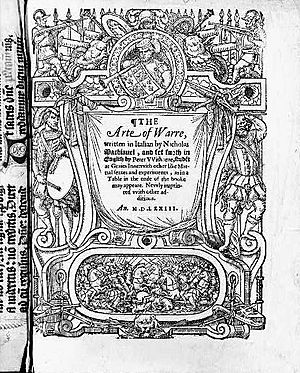

- Dell'Arte della Guerra (1519–1520) – The Art of War, about military strategy.

- Discorso sopra il riformare lo stato di Firenze (1520) – A talk about reforming Florence.

- Sommario delle cose della citta di Lucca (1520) – A summary of the affairs of Lucca.

- The Life of Castruccio Castracani of Lucca (1520) – A short biography of Castruccio Castracani.

- Istorie Fiorentine (1520–1525) – Florentine Histories, an eight-volume history of Florence.

Fictional works

Machiavelli was also a playwright and poet.

- Decennale primo (1506) – A poem.

- Decennale secondo (1509) – Another poem.

- Andria or The Girl from Andros (1517) – A comedy based on an older play.

- Mandragola (1518) – The Mandrake – A five-act comedy play.

- Clizia (1525) – A comedy play.

- Belfagor arcidiavolo (1515) – A short story.

- Asino d'oro (1517) – The Golden Ass is a poem, a new version of an old classic.

- Frammenti storici (1525) – Fragments of stories.

Other works

Della Lingua (Italian for "On the Language") (1514), a discussion about Italy's language, is usually thought to be by Machiavelli.

Images for kids

-

Xenophon, a Greek historian and soldier who influenced Machiavelli.

See also

In Spanish: Nicolás Maquiavelo para niños

In Spanish: Nicolás Maquiavelo para niños

- Florentine military reforms

- Francesco Guicciardini

- Francesco Vettori

- Italian Renaissance

- Mayberry Machiavelli

- Republicanism

- Scipione Ammirato

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |