Portuguese Inquisition facts for kids

Quick facts for kids General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in PortugalConselho Geral do Santo Ofício da Inquisição Portuguese Inquisition |

|

|---|---|

Seal of the Inquisition

|

|

| Type | |

| Type |

Council under the election of the Portuguese monarchy

|

| History | |

| Established | 23 May 1536 |

| Disbanded | 31 March 1821 |

| Seats | Consisted of a Grand Inquisitor, who headed the General Council of the Holy Office |

| Elections | |

| Grand Inquisitor chosen by the Crown and named by the Pope | |

| Meeting place | |

| Portuguese Empire Headquarters: Estaus Palace, Lisbon |

|

| Footnotes | |

| See also: Medieval Inquisition Spanish Inquisition Goa Inquisition |

|

The Portuguese Inquisition (in Portuguese: Inquisição Portuguesa) was a special court in Portugal. It was officially called the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal. This court was set up in 1536 by King John III.

Before this, King Manuel I had asked for the Inquisition in 1515. But it only happened after his death, when Pope Paul III agreed. The Portuguese Inquisition was one of three main Inquisitions at that time. The others were the Spanish Inquisition and the Roman Inquisition. The Goa Inquisition was part of the Portuguese Inquisition, operating in Portuguese India. The Portuguese Inquisition finally ended in 1821.

Contents

History of the Inquisition

How it Started

In 1478, the Pope allowed the Inquisition to start in Spain. This caused many Jews and others to move to Portugal. Before this, Jews in Portugal lived in their own communities. They could practice their religion freely.

But in 1496, King Manuel I made a rule. All Jews had to leave Portugal or change their religion. Not many chose to convert. So, the king closed most ports. This stopped Jews from leaving.

In 1497, an order was given to take Jewish children under 14 from their families. These children were then raised as Christians. In October 1497, Jews who did not leave were forced to be baptized. They became known as New Christians.

Later, in 1506, a mob in Lisbon killed many New Christians. They were blamed for problems in the country. The king punished those responsible. He also gave New Christians the right to leave Portugal. But in 1515, King Manuel I asked the Pope for an Inquisition like Spain's.

In 1531, Pope Clement VII allowed the Inquisition. But he set conditions the king did not like. In 1535, the Pope stopped the Inquisition. He ordered a pardon for those accused of Judaism. He also said prisoners should be freed and property returned. The Pope believed in gentle persuasion, not force. He said some inquisitors acted like "ministers of Satan".

But Pope Clement VII died before his order was fully used. His successor, Pope Paul III, eventually put it into action. King John III of Portugal kept asking for the Inquisition to be re-established. He even got help from his brother-in-law, Charles V.

The Inquisition Begins

After many talks, the Portuguese Inquisition officially started on May 23, 1536. Pope Paul III ordered it. It also began to censor books. The Bible was forbidden in any language other than Latin.

The main targets were people who had changed from Judaism to Catholicism. These were called Conversos or New Christians. Many were suspected of secretly practicing Judaism. About 40,000 people were tried between 1540 and 1765. The Inquisition also targeted people from Africa. They were accused of heresy and witchcraft. Even Romani people were deported from Portugal during this time.

Like in Spain, the king had power over the Inquisition. But the Portuguese Inquisition often acted on its own. It was led by a Grand Inquisitor. The Pope named this person, but the king chose them. The first Grand Inquisitor was D. Diogo da Silva. Later, Cardinal Henry, King John III's brother, became Grand Inquisitor. He later became king himself.

There were Inquisition courts in Lisbon, Coimbra, and Évora. For a short time, there were also courts in Porto, Tomar, and Lamego.

The first public trial, called an auto de fé, happened in Portugal in 1540. The Inquisition focused on finding people who had converted but were not truly Catholic.

The Portuguese Inquisition also operated in Portugal's colonies. This included Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa in India. It continued its work there until 1821.

Under King John III, the courts also censored books. They handled cases of divination, witchcraft, and bigamy. The Inquisition affected many parts of Portuguese life. This included politics, culture, and society.

Many New Christians moved to Goa in the 1500s because of the Inquisition. They were secretly practicing their old religions. The Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier asked for the Goa Inquisition to be set up in 1546. This was to deal with false converts. The Inquisition started in Goa in 1560. Many people were punished for offenses related to Judaism and Islam.

The Goa Inquisition also targeted Hindus. It punished Hindus who practiced their rites publicly. It also punished those who stopped others from converting to Catholicism. Records show that 57 people were burned to death in Goa. Another 64 were burned in effigy (a statue of the person).

The Inquisition also targeted some Portuguese Christian traditions. One was the Cult of the Holy Spirit. This tradition dated back to the 13th century. It was popular in Portugal and its colonies. The Inquisition tried to stop it after the 1540s. This tradition was practiced by ordinary people. It did not involve the clergy. It also spoke of a future time when the Church might not be needed. The Church and Inquisition did not like this idea.

The Cult of the Holy Spirit survived in the Azores Islands. The Inquisition's power did not reach there as strongly. It also survived in parts of Brazil and among Portuguese settlers in North America. Rosa Egipcíaca, an Afro-Brazilian religious mystic, was imprisoned by the Inquisition. She wrote the first book by a black woman in Brazil. She died while working in the Lisbon Inquisition's kitchen.

The ideas of Sebastianism and the Fifth Empire were also sometimes targeted. These were seen as unusual or even against Church teachings. But the targeting was not always consistent. Some important people linked to the Inquisition were Sebastianists.

In 1577, King Sebastian had money problems. He allowed New Christians to leave freely. He also banned the Inquisition from taking property for 10 years.

King John IV banned property confiscation in 1649. He was later excommunicated by Rome, but he died before it was official. This law was fully removed around 1656.

From 1674 to 1681, the Inquisition was stopped in Portugal. Public trials were paused. Inquisitors were told not to order executions or property seizures. This was due to the efforts of Father António Vieira. He was a Jesuit who worked to end the Inquisition. He wrote a report for the Pope about the Inquisition's abuses. As a result, Pope Innocent XI suspended it for five years.

António Vieira felt sympathy for the New Christians. He urged King John IV to treat them equally. The Inquisition punished Vieira for his writings. He was imprisoned for three years. He wrote about the terrible prison conditions. In Rome, he spoke out against the Inquisition. He called it a court that took people's money, honor, and lives. He said it was cruel and unfair.

In 1773 and 1774, the Pombaline Reforms ended the "purity of blood" laws. These laws discriminated against New Christians.

The Portuguese Inquisition lost much of its power in the late 1700s. This was due to Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, the Marquis of Pombal. He said the Inquisition's methods were "against humanity." But he also used the Inquisition for his own purposes. His brother, Paulo de Carvalho e Mendonça, led the Inquisition from 1760 to 1770. Pombal wanted the Inquisition to be a royal court, not a church court.

The Portuguese Inquisition was finally ended in 1821. This was done by the "General Extraordinary and Constituent Assembly of the Portuguese Nation."

How the Inquisition Worked

People in the Inquisition

The inquisitors were the main officials. They investigated and judged cases. The courts also had many other officials. They had their own prisons for the accused. There were also familiares. These were members of the Holy Office who were not clergy. They were often nobles. They could carry weapons and make arrests.

Inquisition Courts

At first, six courts were set up in Portugal between 1536 and 1541. These were in Évora, Lisbon, Tomar, Coimbra, Lamego, and Porto. This helped the Inquisition spread quickly. But after 1548, most courts were moved to Lisbon and Évora. This was because the system was too spread out. It also had money problems. The courts became more stable after the 1560s. This was when the Coimbra court reopened and the Goa court was founded.

The Inquisition courts accepted all kinds of complaints. These included rumors and suspicions. Anyone could make a complaint. Anonymous complaints were also accepted. This was if the inquisitors thought it helped "God's service."

A lawyer appointed by the Holy Office was often not helpful. They did not join the accused during questioning. Their role often hurt the accused more than helped them.

Most accusations were against crypto-judaism (secretly practicing Judaism). But there were also many other charges. These included crimes against morality, witchcraft, blasphemy, bigamy, and criticism of the Inquisition itself.

Punishments Used

The authorities wanted to keep religious order. They punished offenders strictly. Common punishments included forced labor, flogging, and exile. Property was also taken away. As a last resort, people could be put to death by fire or garrote. Exile meant a person was removed from their community. This was to "correct" them.

Taking property was one of the most feared punishments. If someone was accused, their property was seized. This was called sequestration. If found guilty, the property was permanently taken and sold. This was called confiscation. Even if found innocent, it was very hard to get property back.

So, being arrested usually meant being punished. The seizure of property often happened with the arrest. This made it seem like the Inquisition wanted people's property. But it was said that only those likely to be convicted were arrested. Confiscations affected whole families. They were left with nothing. Historian Hermano Saraiva said that taking New Christians' money was "much interest." New Christians were often wealthy merchants.

The money from confiscations paid for the Inquisition's costs. It also went to the Crown. This money helped fund the state's war expenses. However, historian António José Saraiva found that inquisitors managed and used most of the money. Little was left for the Royal Treasury. He concluded that the Inquisition was a way to distribute money to its many members.

How Cases Were Handled

Accusations

The process usually began with an "Edict of Grace." Inquisitors would visit a town. They would ask suspected heretics to come forward. People would also make denunciations (accusations). This was the main way to find suspects.

Many people accused themselves. They confessed to heresy. This was because they feared a friend or neighbor would accuse them later. The fear of the Inquisition caused many accusations.

If someone confessed within a "grace period" (usually 30 days), they might be forgiven. They would avoid the death penalty or life imprisonment. They also avoided losing their property. But they had to accuse others who had not come forward. Accusing oneself was not enough.

Anyone who knew about someone else's heresy had to report it. If they did not, they could be excommunicated. They could then be punished for "promoting heresy." If an accuser named others, those people would also be called.

The accused had to prove their innocence. Many people used denunciations for revenge. They accused neighbors or business rivals. The death penalty was usually for those who refused to change their beliefs. It was also for those who went back to their old religion after converting.

The Inquisition accepted all kinds of accusations. Even prison guards could accuse prisoners and be witnesses.

Questioning

Arrests were made by officials or familiares. They were allowed to carry weapons.

The Inquisition's trials were secret. There was no way to appeal decisions. The accused was questioned. They were pressured to confess to the "crimes." Suspects did not know the charges against them. They also did not know who the witnesses were.

Over the years, the Inquisition created rule books. These were guides for dealing with different types of heresy. A key text was Pope Innocent IV's bull Ad Extirpanda from 1252. It had 38 laws on what to do. Other important manuals included those by Nicholas Eymerich and Bernardo Gui. For witches, there was Malleus Maleficarum (the "hammer of the witches"). In Portugal, four "Regiments" (rule books) were written for inquisitors. The last one in 1774 still allowed torture and public trials.

Trials

The Inquisition's rules show how trials worked. After accusations and questioning, an official called the Promoter made the formal accusation.

The Promoter would say the accused was a baptized Christian. Therefore, they were supposed to believe what the Holy Mother Church of Rome taught. But they had done otherwise. The Promoter would ask for the accused to be punished as a heretic. They would ask for them to be given to the state for punishment.

There were not as many accusations as actual facts. Instead, there were as many accusations as accusers. If one fact was reported by different witnesses, it could become many accusations.

The accused did not choose their lawyer. The Inquisition appointed one. This lawyer worked for the Holy Office. They were told to defend the accused well. But if they thought the accused was lying, they had to tell the Inquisition. So, the lawyer could also become an accuser.

Also, the lawyer could not see the case file. They only knew the charges told to the accused. They could not be with the accused during questioning.

The defense mainly tried to show that witnesses were enemies of the accused. The accused did not know who the informants were. They could not question witnesses who might have lied. They knew no details of the charges. No appeal to a higher court was allowed. Historian A. J. Saraiva compared this to the unfair trials in Stalin's time.

The final decision was made by a vote at the Holy Office's Desk.

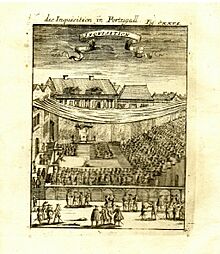

Public Trials (Autos de fé)

The auto de fé was the last step. It included a Mass, prayers, and a procession. Convicts were paraded through the streets. Their sentences were read aloud. Hundreds of people would watch. Kings sometimes attended.

Preparations started weeks before. Scaffolds and seating areas were built. Special clothes called sanbenitos were made for the condemned.

An auto de fé was a grand ceremony. It showed the inquisitors' power. It was also a popular event. People brought snacks as if for a picnic. Reading the sentences could take all day.

Executions never happened at the same place as the auto de fé. Inquisitors did not watch the executions. The condemned were handed over to the state for punishment. In Lisbon, they were marched over a kilometer from the trial site to the execution site.

Opposition to the Inquisition

Father António Vieira (1608-1697) was a Jesuit, writer, and speaker. He was one of the most important people who opposed the Inquisition. He was arrested by the Inquisition in 1665. He was accused of having "heretical" ideas. He was imprisoned until 1667. After his release, he went to Rome. The Inquisition forbade him from teaching, writing, or preaching. His fame and support from the royal family likely saved him from worse punishment.

He is believed to have written a famous anonymous text. It was called "Secret News on How the Inquisition of Portugal Treats its Prisoners." This text showed great knowledge of the Inquisition's inner workings. He gave it to Pope Clement X to help those persecuted.

In Rome, where he stayed for six years, he led a movement against the Inquisition. Meanwhile, in 1673, inquisitors persecuted his relatives in Portugal. Besides his humanitarian concerns, Vieira also saw that the Inquisition was harming New Christians. These were merchants and business people. He knew they were important for Portugal's economy.

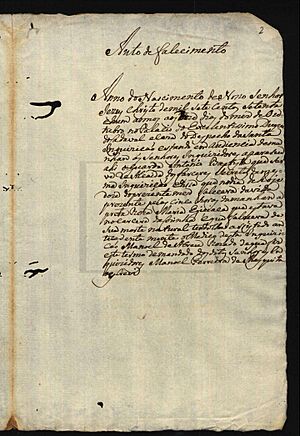

Archives and Records

Most of the original documents from the Portuguese Inquisition are in Lisbon. However, most of the Goa archives were destroyed. The rest were moved to Brazil. They are now in the National Library in Rio de Janeiro.

There are some gaps in the records. For example, data is missing for about fifteen autos de fé in Portugal between 1580 and 1640. Records from the short-lived courts in Lamego and Porto have not been fully studied.

Because of the Inquisition's nature, records can be found in several countries. These include Belgium and the United States.

In 2007, the Portuguese Government started a project. They wanted to put a large part of the Inquisition's archives online by 2010. These archives are at the Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Portugal's National Archives.

In 2008, the Jewish Historical Society of England (JHSE) published the Lists of the Portuguese Inquisition. These lists cover Lisbon (1540–1778), Évora (1542–1763), and Goa (1650–1653). The original papers were collected in 1784. They are now in the library of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. These texts are in original Portuguese. They give a unique look at the Inquisition's activities. They are a key source for historians and genealogists.

Images for kids

See also

- Goa Inquisition

- Spanish Inquisition

- New Christians

- Converso

- Marrano

- Crypto-Jew

- Anusim

- Sebastião de Melo, Marquis of Pombal

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |