Massachusett dialects facts for kids

The Massachusett dialects were different ways people spoke the Massachusett language. These dialects, along with other languages in Southern New England, were so similar that people could often understand each other. It was like how people speaking Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian can often talk together.

The Massachusett language became very important. It was used as a common language, especially by Christian Native Americans. We know a lot about it because many Native speakers wrote things down. Missionaries also wrote books and translated the Bible into Massachusett. Other languages in the area, like Quinnipiac and Coweset, are only known from small pieces of information, like old place names or a few words.

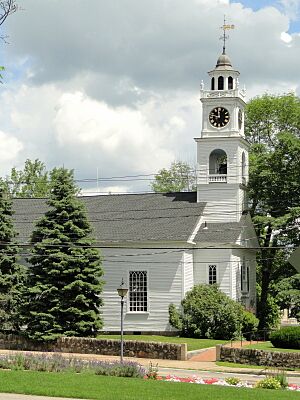

Even though Massachusett was widely used, there were still different dialects. This is because many different groups of people spoke it across a large area. It was even learned as a second language across New England. The dialect spoken in Natick, a "Praying town" (a community for Christian Native Americans), became the most important. This was because the Bible was translated into the Natick dialect.

Many Native American missionaries, teachers, and clerks came from Natick or trained there. This helped spread the Natick way of speaking. People started to adjust how they spoke and wrote to be more like the Natick dialect. This process is called dialect leveling, where differences between dialects become smaller. By 1722, people on Martha's Vineyard, who used to speak very differently, were speaking and writing much like the Natick people.

Some small differences remained, even with dialect leveling. For example, people on Martha's Vineyard used ohkuh for 'earth' or 'land,' while the Natick dialect used ohke. Sometimes, old spellings in documents show these differences.

Contents

Understanding Massachusett Dialects

The Massachusett people's own dialect was likely seen as very important. Elders in Natick told missionaries that Massachusett leaders used to have a lot of power. They could influence other Massachusett-speaking groups and tribes far to the west. This was before diseases and wars weakened their population.

The Massachusett people lived in a central location. This meant their dialect was understood across a wider area. It likely became the basis for a special trade language called Massachusett Pidgin. This pidgin was used for business and talking between different tribes across New England.

The Natick dialect was chosen by John Eliot for his Bible translation. This made it the unofficial standard for writing. Because Natick and its people played a big role in the mission to Native Americans, their dialect also became very respected. This influence caused many dialects to become more similar to Natick speech.

Historically, the Massachusett people lived in the Greater Boston area. This included the shores of Boston Harbor and west towards the 128 beltway. They also lived along much of the South Shore, almost to Plymouth. Later, they were mostly moved to "Praying towns" like Natick and Ponkapoag.

The Massachusett language was spoken until the 1740s. By the early 1800s, it likely had no native speakers left. However, today, two state-recognized Massachusett tribes still use the language for cultural and religious purposes.

Wampanoag Language and History

The Wampanoag language, called Wôpanâôt8âôk, had different forms. This was especially true for communities on islands like Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard, and Nantucket. The Wampanoag people lived across southeastern Massachusetts and parts of Rhode Island. Their name means 'east' or 'dawn.'

Today, people who speak Massachusett are learning the revived Wampanoag dialect. This is thanks to the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project. These speakers come from the Aquinnah, Assonet, Herring Pond, and Mashpee tribes. Historically, the Wampanoag were also known as the Pokanoket. This was a group of Wampanoag tribes working together.

Being on islands made the Wampanoag language very diverse. John Cotton, a missionary, noted that islanders and mainland Wampanoag sometimes had trouble understanding every word each other said.

Islands like Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard had unique features in their speech. Martha's Vineyard had the most different dialect. Even with dialect leveling, old documents from Martha's Vineyard still show unique words. For example, they used nehpuk for 'my blood,' instead of the standard nusqeheonk.

The Wampanoag on Cape Cod and the Islands were lucky. They were mostly safe from King Philip's War. Their population even grew after the war. Many Native Americans joined larger settlements where English settlers were more accepting. This helped the spoken language survive as the main language until the 1770s. The last native speakers on Martha's Vineyard died in the late 1800s.

Today, the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project is very successful. There are now 15 new speakers and over 500 students learning the language. They have created teaching materials, a dictionary, and a grammar. There are nearly 3,000 Wampanoag people in federally and state-recognized tribes today.

Pawtucket Dialect

The Pawtucket people were a group of tribes living north of the Massachusett. Their lands included the North Shore, Cape Ann, and the Merrimack Valley. Before English settlers arrived, the Pawtucket were likely part of the Massachusett Confederacy. But as the Massachusett people weakened, many Pawtucket tribes came under the influence of the Pennacook. The name pawtucket means 'at the waterfall,' referring to the Pawtucket Falls.

We know little about the Pawtucket dialect. A vocabulary list from 1634 shows that the Pawtucket spoke a language very similar to Massachusett. Even early missionaries like Daniel Gookin and John Eliot thought they spoke essentially the same language.

The Pawtucket dialect likely died out by the early 1700s. Many Pawtucket people moved north to join the Pennacook. Some joined Eliot's missions and lived in Praying towns like Wamesit. After King Philip's War, those who returned faced many challenges. Their lands were taken, and they were harassed. By the late 1600s, Wamesit was sold, and its people moved north. The Pawtucket no longer exist as a tribe today.

Nauset Dialect

The Nauset dialect was spoken by the Nauset people. They traditionally lived on the Cape Cod Peninsula, east of the Bass River. This included areas like Chatham and Provincetown. The name nôset might mean 'place of small distance,' possibly referring to the narrowness of Cape Cod.

Very little is known about the Nauset dialect. It only exists in place names. It's unclear if the Nauset were a separate group or part of the Wampanoag. They had a different culture because they relied more on the sea for food. However, they might have been a Wampanoag tribe.

The Nauset people no longer exist as a distinct group today. They survived King Philip's War because they were isolated and stayed neutral. Most Nauset moved to Mashpee and joined the local Wampanoag. Many Mashpee Wampanoag today likely have Nauset ancestors.

Coweset Dialect and Narragansett

The Coweset people lived in central and northern Rhode Island. They were located between the Nipmuc and Narragansett tribes. The Coweset were sometimes seen as a Nipmuc tribe. However, they seemed to speak a dialect similar to Massachusett. Their name kꝏwaset means 'small pine place.'

We know very little about the Coweset dialect. From place names, it was an "N-dialect," like Massachusett. It was in a transition area between Massachusett, Nipmuc, and Narragansett. The only evidence comes from Roger Williams' book, A Key into the Language of America. Williams spent a lot of time with the Coweset.

The Coweset people no longer exist as a distinct group today. Many likely joined the Narragansett or other tribes. Some may have moved to Wisconsin with the Stockbridge-Munsee and Brothertown tribes.

Comparing Different Dialects

Experts have tried to understand and bring back the Narragansett language. They compare it to Massachusett and try to figure out how languages change over time. Even if only using Narragansett materials, the language would still be similar to other Southern New England Algonquian languages. These languages were probably as related as the Nordic languages (like Danish and Swedish), where speakers can mostly understand each other.

The Massachusett language also spread to Nipmuc areas. Many of Eliot's Praying towns were in Nipmuc country. The Nipmuc people even settled in Natick. James Printer, a Nipmuc man, was a very important translator and printer of Eliot's Indian Bible.

Some Native Americans who stayed away from the Praying towns likely kept their original languages. For example, a French missionary recorded a language in the 1700s near Montreal. It was similar to Massachusett but was an "L-dialect." This might have been the original Nipmuc language, not changed by the standard Massachusett used in writing.

| English | Natick | Wôpanâak (Revived) | Wôpanâak (Plymouth) | North Shore (Pawtucket) | Narragansett (Coweset?) | Loup (Nipmuc?) |

| 'fox' | wonksis | (wôquhs) | wonkqǔssis | peqwas, whauksis | wonkis | |

| 'my mother' | nꝏkas | (n8kas) | nookas, nutookasin, nútchēhwau | nitka | nókace, nitchwhaw | nȣkass |

| 'one' | nequt | (nuqut) | nequt | aquit | nquít | |

| 'duck' | quasseps | (seehseep) | sesep, qunŭsseps | seaseap | quequécum | |

| 'boy' | nonkomp | (nôkôp) | nonkomp | nonkompees | núckquachucks | langanbasis |

| 'deer' | ahtuck | (ahtuhq) | attŭk | ottucke | attuck | |

| 'to kill' | nush | (nuhsh) | nish | cram | niss | nissen |

| 'shoe' | mokis | (mahkus) | mohkis | mawcus | mockuss | makissin |

| 'head' | muhpuhkuk | (mupuhkuk) | muppuhkuk | boquoquo | uppaquóntap | metep |

| 'bear' | mosq | (masq) | mashq | mosq, paukúnawaw | ||

| 'canoe' | mishꝏn | (muhsh8n) | muhshoon | mishòon | amizȣl | |

| 'it is white' | wompi | (wôpây) | wompi | wompey | wómpi | ȣanbai |

| 'man' | woskétop | (waskeetôp) | wosketop | wosketomp | ||

| 'chief' | sachem, sontim | (sôtyum) | sachem | sachem | sâchem | sancheman |

| 'my father' | nꝏshe | (n8hsh) | noosh | noeshow | nòsh | nȣs |

- The word for 'boy' in North Shore seems to have a small ending added.

- The word for 'my mother' in Wôpanâak (Plymouth) seems to have an extra ending.

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |