Mathematics of Sudoku facts for kids

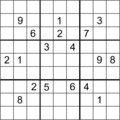

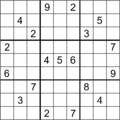

Mathematics helps us understand Sudoku puzzles better. We can find out how many different ways a Sudoku grid can be filled. We can also discover the smallest number of starting clues needed for a puzzle. And we can explore how Sudoku grids can be symmetrical. This is done using special math areas like combinatorics (counting things) and group theory (studying patterns).

Mathematicians look at two main things. They study the properties of puzzles that are not yet solved. This includes finding the fewest clues needed. They also look at the properties of puzzles that are already solved. People started counting the number of solutions around 2004.

For a classic Sudoku, there are a huge number of ways to fill a grid. It's about 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960 different solutions! But if you consider solutions that are just rotated or flipped versions of each other, there are far fewer. There are about 5,472,730,538 truly unique solutions. Only a tiny fraction (about 0.005%) of all filled grids show symmetry. A normal Sudoku puzzle needs at least 17 clues to have only one correct answer. The largest puzzle found so far that is still minimal has 40 clues.

Contents

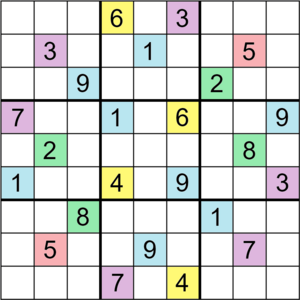

Sudoku Puzzles

Fewest Starting Clues

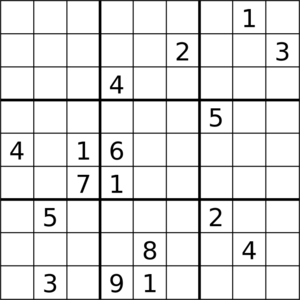

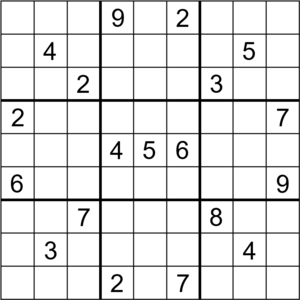

A "proper" Sudoku puzzle has only one correct solution. A "minimal" Sudoku means you cannot remove any clue without making the puzzle have more than one solution. Different minimal Sudokus can have different numbers of clues. This section talks about the smallest number of clues needed for a proper puzzle.

Standard Sudoku

Many Sudoku puzzles have been found with just 17 clues. Finding these puzzles is very hard. In 2014, some researchers used computers to search for them. They proved that 17 is the smallest number of clues needed for any proper Sudoku.

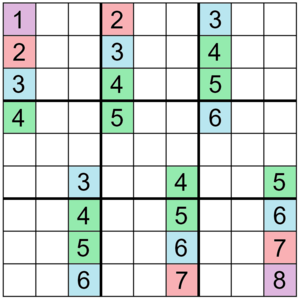

Symmetrical Sudoku

Some Sudokus have special patterns called symmetry. For example, a Sudoku might look the same if you rotate it 180 degrees. The fewest clues for such a puzzle is thought to be 18. Some of these puzzles also have a special property called "automorphism." This means the puzzle can be transformed into itself in a unique way.

A Sudoku with 24 clues is known to have "dihedral symmetry." This means it looks the same if you rotate it 90 degrees. It also has symmetry if you flip it. We don't know if 24 clues is the absolute minimum for this type of Sudoku.

Total Number of Minimal Puzzles

We don't know the exact number of all possible minimal Sudoku puzzles. These are puzzles where you can't remove any clue without losing the unique solution. However, using special math methods, scientists have estimated the numbers.

There are about 3.10 × 1037 different minimal puzzles. If you ignore puzzles that are just the same but with different numbers swapped around, there are about 2.55 × 1025 minimal puzzles.

Sudoku Variations

There are many different kinds of Sudoku puzzles. They can have different sizes, not just 9x9. They can also have different shapes for their "regions" or "blocks." This article mainly talks about the classic 9x9 Sudoku.

A "rectangular Sudoku" uses regions that are shaped like rectangles. Other types have regions with unusual shapes. Some even have extra rules, like "hypercube" Sudokus.

In Sudoku, the starting numbers are called "givens" or "clues." A "proper" puzzle has only one solution. A "minimal" puzzle is a proper puzzle where you cannot remove any clue.

Math Behind Sudoku

Solving Sudoku puzzles on larger grids (like 16x16 or 25x25) is a very hard problem for computers. It belongs to a group of problems called "NP-complete." This means it gets much, much harder as the grid size grows.

You can think of a Sudoku puzzle as a "graph coloring" problem. Imagine each cell in the Sudoku grid is a point (called a "vertex"). If two cells cannot have the same number (because they are in the same row, column, or 3x3 block), you draw a line (called an "edge") between their points. The goal is to color each point with a number from 1 to 9. The rule is that points connected by an edge must have different colors.

A completed Sudoku grid is also a type of Latin square. A Latin square is a grid where each number appears only once in each row and column. Sudoku adds an extra rule: each number must also appear only once in each 3x3 block. This means there are fewer Sudoku grids than Latin squares.

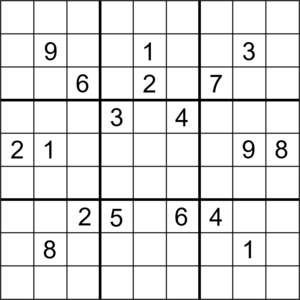

Sudokus from Group Tables

Mathematicians can use special tables from "group theory" to create Sudoku puzzles. These tables are called "Cayley tables." They show how numbers or elements combine in a group.

For example, imagine a group where you add pairs of numbers. If you arrange these additions in a table, you can sometimes create a Sudoku grid. This involves understanding "subgroups" and "quotient groups," which are smaller groups found within a larger one.

This method can create many Sudoku grids. However, it's clear that not all Sudoku puzzles can be made this way.

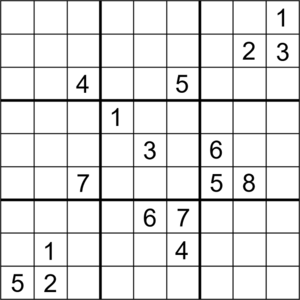

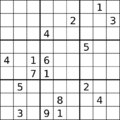

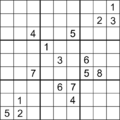

Jigsaw Sudokus

A Jigsaw Sudoku is a puzzle where the regions are not always square or rectangular. They can have irregular shapes, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. For some sizes, it's even possible that no Latin square can fit these irregular shapes, meaning no Sudoku puzzle on such a grid would have a solution.

Sudoku Solutions

The number of Sudoku grids depends on how you count them. Do you count every single grid as different, even if it's just a rotated version of another?

Standard Sudoku Solutions

All Possible Solutions

When counting "all" solutions, every single grid is considered unique. This means if you rotate a solved Sudoku grid, it counts as a new, different solution. Even though symmetry helps in counting, it doesn't change the final total.

The first person to count all possible solutions was QSCGZ in 2003. He found there are 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960 distinct solutions.

In 2005, other researchers confirmed this huge number. They used a method that looked at how the top rows could be arranged. Then they counted how many ways the rest of the grid could be filled. This confirmed the earlier result. Later, an even faster counting method was developed.

Truly Unique Solutions

If we consider solutions that are essentially the same (like rotations, flips, or swapping numbers), the number of unique solutions is much smaller. This is where "symmetry groups" come in.

Mathematicians use a concept called "Burnside's lemma" to count these truly unique solutions. They look at how many grids stay the same or become a different version of themselves after certain transformations. Using this method, Ed Russell and Frazer Jarvis were the first to find the number of truly unique Sudoku solutions: 5,472,730,538.

It has been shown that all ways to rearrange cells in a Sudoku grid that still result in a valid solution are part of this "sudoku symmetry group." This is true even for larger grids.

See also

- Combinatorial explosion

- Dancing Links

- Glossary of Sudoku

- Sudokian

- Sudoku code

Images for kids

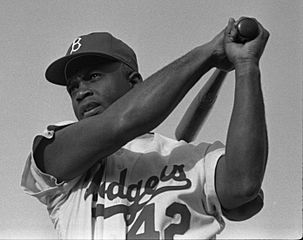

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |